Donald Trump’s presidency is well underway, but many observers are still trying to understand how he won the office in the first place. Plenty of explanations are circulating, from Hillary Clinton’s weaknesses as a candidate to pervasive sexism and class disenfranchisement in the Rust Belt. But whatever the truth, those who worked tirelessly on behalf of Trump have got what they were after.

A small subset of these campaigners is worth special attention. Not so much because of their political convictions but because of their unrestrained fervour to fulfil an ancient Egyptian prophecy involving Trump, a cartoon frog, and an online counterculture.

The story starts with the infamous online image board 4chan, which has been a weather-vane of internet subculture since its conception in 2003. 4chan is divided into sub-forums about topics ranging from video games and anime to politics. Users communicate largely through memes – images somehow grounded in pop culture and featuring a recurring character, figure or phrase. Around 2010, 4chan users began posting and reposting the image of a cartoon frog, Pepe. By 2015, his wrinkly, wide-eyed face had become a staple meme within the community.

The sub-forum “/pol/” caters to the internet’s extreme fringe: anarchists, communists, far-right extremists and white supremacists. /pol/ is 4chan’s second most popular sub-forum, and is one of the main forces that set the tone for online fringe political discussion.

Pepe the frog and /pol/ first collided with the outside world in June of 2015, when Trump announced his candidacy for president of the united states. Trump, with his aversion to “political correctness” and penchant for flair and showmanship, was /pol/’s immediate candidate of choice. And so, Pepe the frog was edited to wear a “Make America Great Again” hat, and began appearing in hundreds of Trump-supporting forum posts.

At that very time, an event of religious significance to /pol/ contributors was approaching.

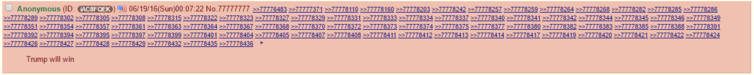

Each post published on 4chan bears an identifying number, assigned consecutively by order of publication. Because of the huge number of posts published every day, this number is practically random. 4chan has an old tradition of users trying to have their posts obtain certain special numbers, known as “gets”. The most precious “gets” are round numbers (such as 1m) or those that repeat all their digits. By October of 2015, /pol/ was approaching its 77777777th post, seen to be of particular importance because the number 7 is often associated with good luck and fortune. The post that would “get” that number was sure to gain legendary status within the community.

As it happened, the 77777777th “get” was for the message “Trump will win”.

The 77777777th post on 4chan’s /pol/ sub-forum. Author providedThis sent /pol/ and the broader 4chan community into paroxysms of amazement and glee. To fulfil this prophecy, the sub-forum started an online campaign in support of Trump. Users on /pol/ believed that the best way they could help Trump’s chances of victory was by creating and spreading pro-Trump internet memes outside of 4chan. They called it the “meme war”: if they could expose regular social media users (“normies”) to as many pro-Trump memes as possible, Trump would forever dominate the online news cycle, giving him a better chance of winning the primaries and maybe even the presidency.

It was from this melting pot that the cult of Kek emerged.

Hail Trump

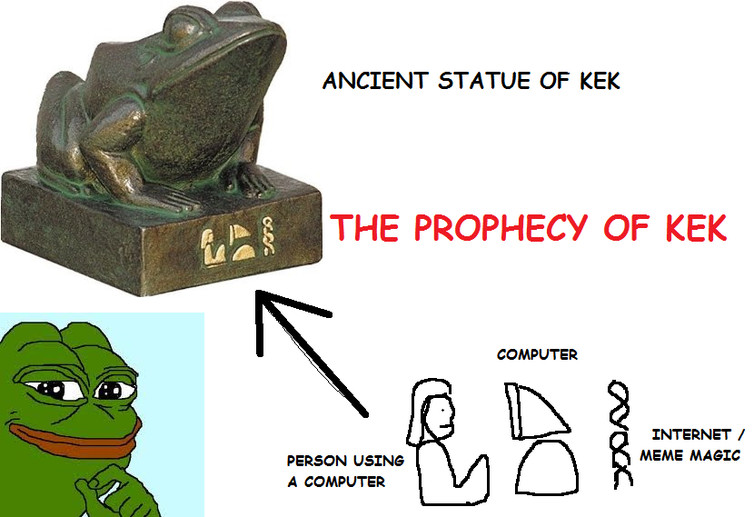

The word “Kek”, originally a Korean onomatopoeia for a raspy laugh, had long been used on 4chan as a replacement for “lol” (laughing out loud). One day, a /pol/ contributor discovered that Kek is also the name of an ancient Egyptian frog god.

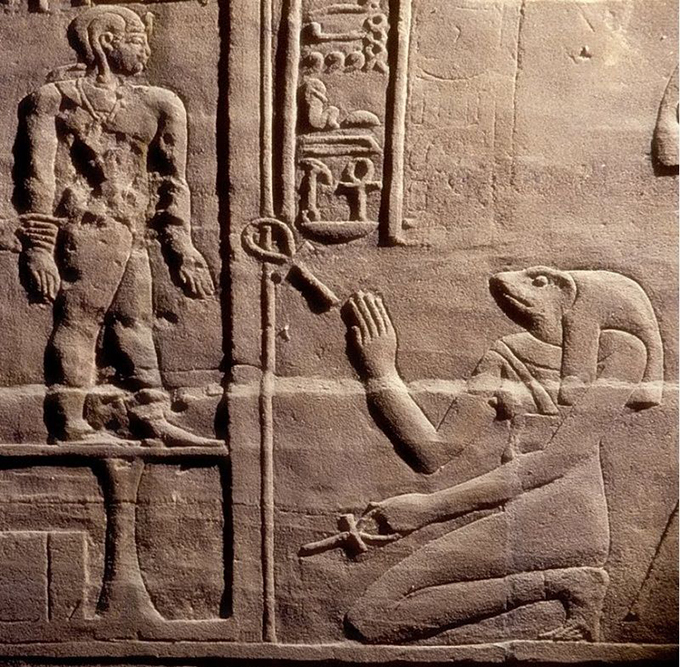

The similarities between Kek and Pepe were striking enough as it was, but Kek also has a female alter ego, or nemesis, that takes the form of a snake. This was quickly taken to symbolise Clinton, a universally reviled character within the /pol/ community. What’s more, to our modern eyes, the hieroglyphs supposedly used to write the name Kek in ancient Egyptian even strongly resemble a man sitting in front of his computer.

Some of this, incidentally, is simply incorrect. According to an Egyptologist we contacted, Kek – which perhaps fittingly means “darkness” in ancient Egyptian – is not in fact a frog god per se, but rather one of four male Egyptian gods who are usually depicted with frog’s heads. Their female counterparts are depicted with serpentine heads. The hieroglyphs on the frog statuette above actually spell “Heqet”, which is the real name of the Egyptian frog goddess often associated with fertility and procreation.

Historical inaccuracies notwithstanding, this series of coincidences proved too much for the 4chan community to ignore, and the cult of Kek was born. The frog-headed Kek became the father, Pepe the holy spirit, and Trump the son, sent to Earth to fulfil a divine destiny.

Kek’s followers busied themselves disseminating Pepe memes everywhere on the mainstream internet. The Clinton campaign mistakenly their efforts to a Nazi-esque ideology, and declared Pepe a public enemy – a grave misunderstanding of online counterculture. Until then, Pepe had been a harmless meme on the mainstream internet, with celebrities like Katy Perry retweeting images of him; sudden demonisation by the Clinton campaign endowed the cult with a remarkable legitimacy.

Kek cultists and 4chan’s Trump followers flocked to vote in online post-debate polls, racking up huge Trump margins. Trump repeatedly cited these results as proof of his debating prowess, although the polls concerned allowed people to vote more than once. This allowed him to present a narrative of unstoppable victory, even in the face of what would normally have been campaign-destroying scandals.

What this saga means for the future role of the internet in political campaigning isn’t yet clear, but a precedent has been set: no matter how bizarre or misinformed, the collective power of tens of thousands of internet cultists appears to works wonders.

Author Bios: Adrià Salvador Palau is a PhD Student in Asset Management and Jon Roozenbeek is a PhD Student in Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge