In Australian public discussion recently, the idea that current university arrangements fulfil a truly valid role for students has been challenged.

During the 1960s, the challenge from social critics was universities merely “credentialised” the pretensions of the elite, to validate their claims to positions and occupations of privilege on meritocratic grounds.

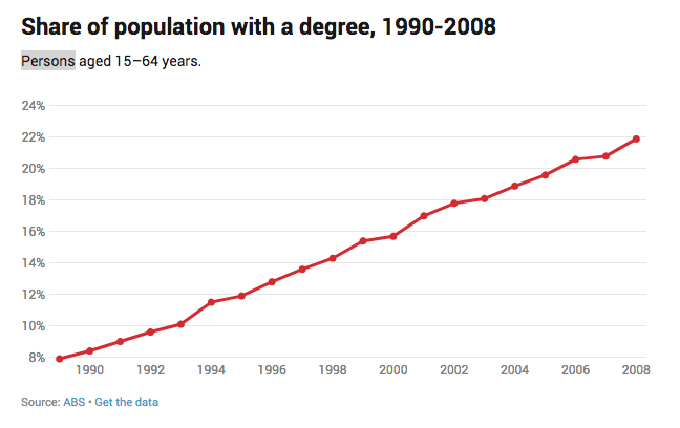

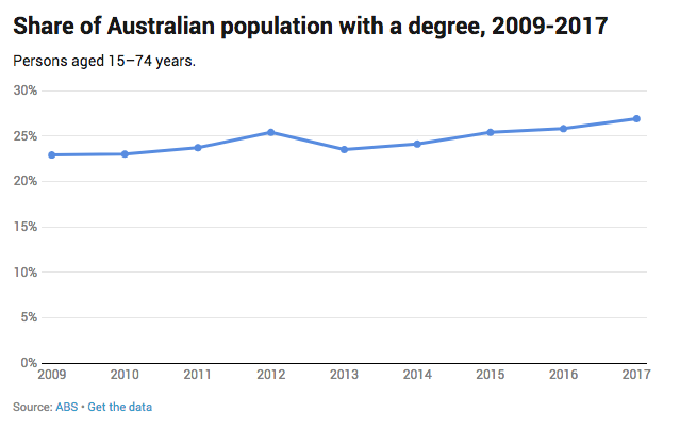

The extension of the modern university to greater participation followed over the next 50 years.

Now, the critique is from the right side of politics. It states too many people are undertaking university studies when those studies are a waste of time and money. They don’t improve capabilities and skills, except for a few narrow areas. General public expenditure on universities should be cut, reducing deficits and/or taxes.

What has been the benefit of university expansion?

Certainly, in terms of social equity, extending the opportunity to attend university to the general public has not actually changed the class structure of participation dramatically. But there are other fundamental social advances.

The key gain has been a large female participation increase, with 58% of domestic enrolments in recent years and a majority since 1987. There’s also some other equity group growth, such as in disability, regional, and Indigenous enrolments. That said, it’s important to separate absolute numbers increase from improved shares of the student population.

What are the general benefits beyond equity?

The personal development benefits long seen as arising from university education continue as ever. Though, personal benefits aren’t simply reflected in economic measures, such as income. In some areas, intangible rewards can come strongly at the expense of higher incomes. Fields ranging from social work and divinity through to visual and performing arts illustrate the point. Even so, research can calculate the income foregone by such commitment, which is a missing figure from blunt measures such as GDP.

There are also many other well attested non-economic public and personal benefits. These range from improved personal health care and child development, to democratic attachment and community participation. Increasing care is being exercised in the research to ensure it measures additional personal benefits from education, controlling for other personal characteristics. This might include family background or income level.

At the same time, there is substantial net benefit demonstrated for such directly material measures, such as GDP and GDP per capita. The high income countries have high spending per person on higher education. And the spending is shown to help strongly drive those higher average incomes.

More immediately, regular surveys of graduate outcomes show ongoing substantial advantage for university studies in terms of employment participation. And for earnings, relative to comparisons such as school leavers with no further study.

Separately, twins’ studies also suggest the returns are not simply innate ability or even upbringing.

Opinion surveys supplement these and ask graduates and employers their views on the value of the training, with broadly supportive results. That said, the extent to which universities convey general skills that can enhance any job as opposed to specialised skills, is not well researched. This needs more attention, as does the measurement of so-called “overqualification” which may accordingly be exaggerated.

University is worth it

The key point for the present and foreseeable future is that universities continue to offer rates of financial return on investment well ahead of the social cost of capital. When intangibles private benefits and the broader net public benefit discussed above are added, the case is even stronger. And evidence indicates returns are perhaps high too for research and for vocational education and training, including both TAFE and private training.

University spending more than pays its way, including for public budgets for future generations, and should be compared carefully to other spending. For example, company tax cuts on their own will contribute less to jobs and growth than deploying that funding for universities.

Of course, there are lessons to be learned regarding areas of some decline here and areas of some dissatisfaction there. But to return to government quotas and micro-management instead of demand-driven enrolments, risks a suite of problems of its own.

Equally, it should be recognised that Australia already has one of the lowest share contributions of public funding to universities in the OECD. The tail wagging the dog and binding it in red tape, is not a pleasant prospect.

Constructive reform of the system, its funding and how it works can happen. But success requires good policy design and implementation. At present, Australia’s universities do well by our society – and can do more with good leadership, partnership and support.

Author Bio: Glenn Withers is a Professor of Economics at the Australian National University