As students return to universities across Canada and the United States this month, the safety of female students is a major concern. Sexual violence occurs on all campuses and can no longer be ignored.

It’s now widely recognized that universities and governments need to invest deeply in prevention. The province of Quebec, for example, recently announced a $23 million investment into campus sexual assault policies and prevention.

Less widely recognized is the importance of empowering women to talk about desire. This is a vital part of any comprehensive solution to campus sexual assault.

As a psychology professor who studies male violence against women, I have spent the last 10 years developing the Enhanced Assess, Acknowledge, Act (EAAA) Sexual Assault Resistance program. The program is designed for women in the first year of university, because that’s when the risk of sexual assault is highest.

The EAAA program is the only campus education program proven to decrease sexual violence. Study results show that attending women were 46 per cent less likely to experience rape and 63 per cent less likely to experience attempted rape or other forms of sexual assault in the next year. Women who took EAAA also benefited from lower rates of sexual assault two years later.

Women also increased their ability to detect risk in men’s behaviour and their confidence in asserting their rights. They learned, and became more willing to use, the most effective verbal and physical strategies for defending themselves. Importantly, these changes were accomplished while substantially decreasing women’s (already relatively low) beliefs in rape myths and woman-blaming.

Sexual desire at the centre

So how does EAAA accomplish all this? In 2001, prominent sexual violence researchers Patricia Rozee and Mary Koss synthesized a decade of rape research and suggested the Assess, Acknowledge, Act (AAA) components of an effective program for women. I brought the idea to life and added an “enhancement” — emancipatory sex education. This puts women’s own values and desires at the centre of the discussion.

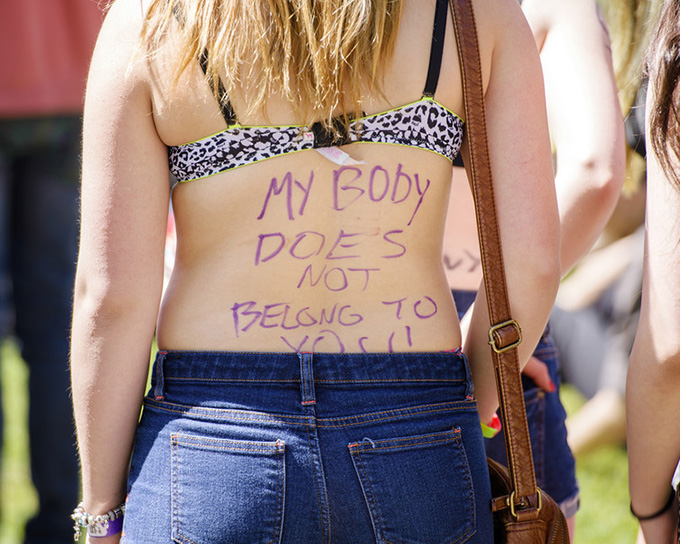

Helping women to explore their sexual desires and communicate their needs is critical to reducing sexual assault. (Shutterstock)

The EAAA program focuses on sexual assault by acquaintances and adds to women’s existing strength, knowledge and skills. It provides space for them to explore their sexual and relationship goals and desires. It reinforces, with knowledge and skills, their rights to seek and engage in sex they do want, to resist sex they don’t want and to fight back against threats to their bodily integrity.

EAAA is never prescriptive. The goal is to increase women’s options so that they are able to participate in their lives fully and without fear.

Asserting sexual needs

Most of the media coverage about the EAAA has focused on the Act unit which includes two hours of self-defence originating in a long tradition of feminist self-defence in Canada and the United States. This is definitely a critical element of EAAA and the reduction in completed sexual assaults. But that doesn’t explain how EAAA reduces attempted sexual assaults even more dramatically.

The final Relationships & Sexuality unit is likely responsible. This provides women with sexual knowledge. It offers time for exploring their sexual desires and practice in communicating their interests (in, for example, a specific sexual act) and asserting their needs (for safer sex, for example). It provides a positive sexuality frame within which resistance to sexual assault is contextualized.

Greater sexual knowledge and confidence around desires and values makes coercion visible earlier. If a woman sees coercion earlier, then her options for leaving or resisting in other ways are greater.

Holding women responsible?

Some feminists have expressed the view that all interventions for women are implicitly or explicitly holding women responsible for men’s behaviour.

I agree that many campaigns have done this. Women are still being told (by parents, media, posters and talks on campus) that they should restrict their behaviour in various ways. That they should limit where they go and when, how they dress and how they behave — to stay safe. This “advice” is based on myths, not evidence. These social precautions interfere with a woman’s quality of life without providing actual protection, especially since most danger comes from men whom women already know.

The EAAA program for women undermines these messages. The program makes it clear that there is no risk in any situation unless there is a man present who is willing to engage in coercive behaviour. “Risk factors” (such as isolation or the presence of alcohol) are described as circumstances which provide perpetrators with certain advantages. Women brainstorm ways of undermining those advantages and come up with strategies that work for them personally.

Our research findings show that this message about perpetrator responsibility gets through; women decrease their belief in woman-blaming explanations for rape. And EAAA is beneficial for women even if they are sexually assaulted after they take it. Survivors who have taken EAAA blame themselves less than do survivors who did not receive the program.

Beyond bystander education

Universities need to invest deeply in effective prevention to reduce campus sexual assault. I, like many feminists on campus, would like universities to “tell men not to rape.” Unfortunately, the research evidence shows us that the available educational programs for men do not work to accomplish their goals. Only comprehensive strategies working on multiple levels will produce the individual and campus-wide changes we are striving for. Large and sustained changes cannot be accomplished with brief interventions or during one occasion during a university orientation.

A range of sexual education efforts are required on campus to shift ‘rape culture.’ (Shutterstock)

The relatively recent focus on bystander education is one prevention option endorsed in Canada, the United States and the CDC. And it’s a good choice. Bystander programs have been shown to change students’ attitudes toward intervening when they see a problem. More importantly, they increase students’ actual intervention behaviour.

But these bystander programs weren’t designed to, and do not, decrease sexual assault perpetration or victimization in the short term. Additionally, most sexual assaults occur in circumstances where no one is present who could intervene. So they’re primarily effective in increasing interventions in “precursor” settings where risk is elevated (for example, where a man overhears his friend say that he doesn’t care what it takes, he is going to “hit that” tonight) but a sexual assault has not begun.

A comprehensive solution

If a good bystander program is delivered broadly and in a sustained way on any campus, over time, we expect that a culture shift will occur. In this context, not only would social norms stop supporting a “rape culture,” but perpetrators would also find it extremely difficult to act unnoticed and uninterrupted. Unfortunately we aren’t there yet.

Empowering women is, therefore, another critical piece of a comprehensive solution to the problem of sexual violence. EAAA empowers women students with the resources they need to defend their own sexual rights. It does this within a positive sexuality frame that fits well with other sexual education efforts on campus, such as sexual consent education.

Author Bio: Charlene Senn is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Windsor