Good advice on how NOT to be an academic when you finish your PhD is pretty thin on the ground. Many supervisors have never done anything else, and/or are not well enough connected with industry to know what is ‘hot’. Careers centres at universities tend to shape their offerings around the huge undergraduate cohort, who have very different needs.

Good advice on how NOT to be an academic when you finish your PhD is pretty thin on the ground. Many supervisors have never done anything else, and/or are not well enough connected with industry to know what is ‘hot’. Careers centres at universities tend to shape their offerings around the huge undergraduate cohort, who have very different needs.

If you want to leave academia at the end of you PhD it’s likely you will face some kind of career transition. While we train astrophysicists, we don’t have any astrophysics companies in Australia. Nor does industry seem to recognise disciplines like anthropology. If you want to leave academia, in many cases, you have to become someone else. Professionally at least.

In fact, there’s a whole range of careers out there you have probably never heard of while you were busy writing your dissertation, but they are hard to recognise. Out there, the skills you learn as an astrophysicist is more likely to be packaged in a job called ‘data scientist’; on the humanities side, an anthropology graduates might be suitable for a job called ‘UX designer’.

Many non-academic employers have hard problems to solve and would really value your skills. The problem is – how do you find each other?

I’ve been researching the complex issues around PhD graduate employability for some three years now. My colleague Rachael Pitt deserves the credit for starting me on this path. Our first project together resulted in a paper called ‘Academic superheroes: a critical analysis of job descriptions for the purpose of employability.’ In that paper we treated academic job ads as ‘wishlists’ where universities are describing the perfect candidate and performed a simple content analysis using the Researcher Development Framework from Vitae.

The premise of this initial research was: if you know what skills and attributes are most prized by universities, you can work backwards to the skills programs you want to offer. This ‘market research’ of academic employers gives us some data to guide PhD students who want to become academics. The results of that research were well received by the community and immediately useful to people like myself, who have to plan transferable skills programs.

The obvious next step was to repeat the process with non academic jobs, to see what skills and capabilities industry wants. But it was here that we hit what turned out to be a 2 year snag.

How do you decide what non-academic job is relevant to an analysis? Non-academic employers don’t tend to use the word ‘PhD’ in their job ads. If you type that term into a database you probably only see academic jobs. Yet, many employers, especially in knowledge intensive economies like Australia, are looking for people do highly complex jobs that involve research in some way.

I was stuck on this problem until my colleague Dr Will Grant from the Centre for Public Awareness of Science saw me present the findings from the Pitt / Mewburn study and was immediately interested in the problems I sketched out. Afterwards we had a coffee that turned out to be the start of a beautiful research collaboration.

Our initial idea was to find money for research assistant time to identify enough, relevant non-academic jobs and then repeat the procedure Rachael and I developed. Will made the genius suggestion that we approach the government for money. Since we are lucky enough to be located in Canberra, our nation’s captial, we literally walked across the road and had a meeting with Will’s contact in the Department of Industry.

The government were interested in funding research into the problem, but sent us back inside ANU to seek help from machine learning specialists. This was a research direction Will and I had not thought about at all, but ended up being amazing. Our initial inquiries led us to the clever people at Data61, in particular A/Prof Hanna Suominen. Hanna is an expect in Natural Language Processing as well as machine learning. Luckily, as a research supervisor and passionate educator, she was interested in the problem of PhD employability too.

To cut a very long and interesting story short, over the last two years Hanna inducted Will and I into some of mysteries of advanced big data / machine learning research techniques. As a primarily qualitative researcher, it’s been exciting to be able to participate at the leading edge of this emerging science. Machine learning enables qualitative research at a scale that is normally impossible ‘by hand’. (Along the way we have had lots of fun too. I count Will and Hanna as friends as well as trusted work colleagues, a lovely side-effect of this project).

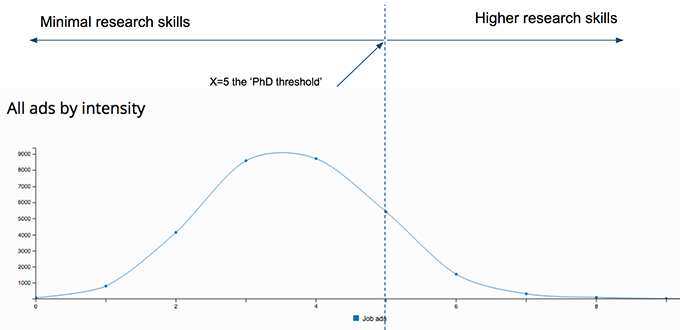

Together we managed to design an algorithm that can ‘read’ job ads and rank them according to research skills intensity. Australia’s biggest online jobs market place, Seek.com.au, generously gave us every job ad from 2015 for our experiments. It took much longer than we thought (of course), but we did manage to measure the magnitude of the ‘hidden’ job market for PhD graduates in Australia, which we expressed as a distribution curve:

We’ve drawn the ‘PhD threshold’ conservatively at x=5. For those who remember their high school calculus, the area under the curve to the right of the threshold line represents the magnitude of the ‘hidden’ job market for PhD graduates. In case you’re wondering, it’s roughly 5334 jobs in our Seek data set from 2015 – enough for every available PhD graduate in Australia. Probably more than enough if you believe the research that suggests that only about a third of jobs are ever advertised in the first place. Around 80% of employers who wanted PhD level skills, did not mention the PhD at all, confirming the hunch that non academic employers don’t understand what a PhD graduate can do for them (oh, and there was one job for an anthropologist – but no one was looking for an astrophysicist. Sorry).

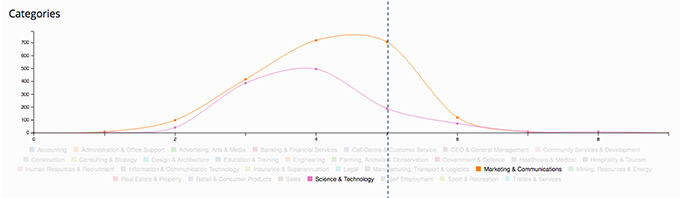

However, the ‘PhD shaped’ jobs weren’t where you might expect to find them. Consider the following graph, which compares the relative job market for people specialising in marketing and communications (orange), vs science (pink):

We train many more PhDs in science than we do in marketing and comms, but marketing and comms clearly has a much greater need for high level research skills. Why? They are grappling with an entirely new business model – it’s all about tracking and analytics now. Lots of marketing people are trying to work out where and when you might buy something so they can put targeted, even personalised, advertising in your way. The advanced technical skills needed for this work is much more likely to be taught in an astro-physics course than a marketing one. This is one reason for the massive shortage of data scientists, highlighted in this report on the ‘Quant Crush’ from Burning Glass.

There are big implications in this research for all of us in the business of research education. Should we be telling astro-physics graduates to look for a marketing job? Or should we change how we approach teaching marketing and comms to include these skills, and enrol heaps more students? Do we even need to be responsive to employer needs at this granular level when it’s likely, with technological changes, these needs change continuously?

These are still open questions we are exploring, but if you are interested and want to go full nerd, you can download our newly released “Tracking Trends in Australian Industy” report here.

In the meantime, our annoying research problem has unexpectedly become a most useful and fruitful research direction. Hanna, Will and I are now exploring the commercial possibilities of our algorithm. As I said earlier, Job ads are interesting and useful wish lists. By exploring the market for your skills via job ads, you can work out what research techniques are in demand, or what software packages / programming languages you should you learn. Universities are storehouses of learning that you can tap to develop yourself in all kinds of ways. All kinds of learning is available for free (or at least for cheap): courses, amazing mentors, online learning, libraries full of books and resources. With knowledge of where you are going, you can start to engage with industry and seek the experience that will make you a credible candidate, perhaps via an intern program.

Yes, it’s challenging to fit this ‘extra’ work into your PhD, but it’s an investment in your future. Our app will make this process much easier by putting the power of our algorithm in your hands. Our data insights can help you see what kinds of jobs you might be able to do, what kind of skills and experiences will make you competitive, and where the jobs are. This helps you make and action concrete career plans – hopefully settling some of the uncertainty that many feel, particularly towards the end of the PhD. We plan on making searching intuitive and fast, using the latest machine learning tools. Importantly, we believe in keeping this technology free for PhD students and graduates if we can. We’ll have to be creative to achieve this, but I’m reasonably confident we can make it work.

We aim to have a (free) beta version of ‘PostAc’ TM (App. No. 1872576) available by next May. If you’re interested in participating in the testing of the demonstration version, you can sign up here.

Obviously there is a lot more work to do yet, but I’m interested in your initial reactions to this body of research. Are you confused about how to get a non academic job? What information or data do you think you need to help you make good choices about developing your skill set? What are the challenges in making what is essentially a career transition to become ‘something else’ at the end of your PhD?