Insects are everywhere – in backyards, balconies and the park down the street.

In fact, numerically speaking, insects dominate the Earth with more than 5.5 million species. An estimated 10 quintillion – or 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 – individual insects are alive at any given moment.

Because insects are small and readily available and can easily be kept in the classroom or at home, as insect researchers we believe they are ideal for teaching children about nature – which can in turn get them excited about science. So we conducted a survey to learn more about how public schools use insects.

Teachers prefer vertebrates

We surveyed 262 K-12 teachers in 44 states regarding the kinds of animals they use in their classrooms. Of the teachers who responded to this 2019 survey, six taught preschool, 62 taught elementary school, 44 taught middle school and 147 taught high school. The rest taught at all levels of instruction.

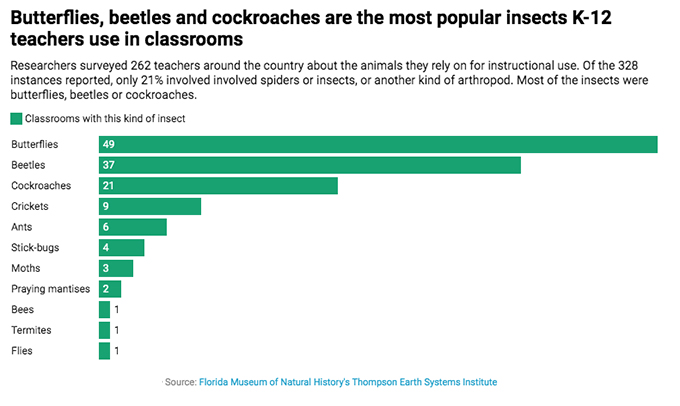

We found that teachers were most likely to choose vertebrates for education in the classroom, with 328 instances of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles. We also found 144 instances of invertebrates, including insects, worms, spiders and crustaceans – such as crabs and shrimp.

The most common insects were butterflies, followed by beetles and cockroaches.

About 2 in 3 of the surveyed teachers said they do not keep insects or spiders in their classrooms because they prefer other animals. Another 1 in 6 said it was because they do not like insects. The responses show how rare it is for teachers to use insects in their classrooms and the small number of insect species they select for this purpose.

Experiencing nature

Although many people are afraid of insects, they are a great teaching tool for many reasons. For example, insects are useful for an extraordinary range of lessons, from metamorphosis to diversity. They also tend to be inexpensive and easy to care for.

One reason we encourage teachers to use insects in their classrooms is that we’ve observed that interacting with insects can help children appreciate nature. Rearing butterflies and moths in classrooms, or simply observing these insects outside, gives students the opportunity for a hands-on learning experience. More often than not, observing these insects leads to further inquiry and curiosity about the natural environment in which they’re found.

We believe that by keeping insects in the classroom, young children have a chance to learn more about these animals. Insects are often feared or dismissed because of stigma in popular culture and general disgust. As entomologists, we believe that introducing insects in the classroom, paired with teaching students about insect behavior and environmental roles, will give students a safe place to observe and appreciate these organisms.

Studies in the U.S., Norway, China and Japan have all found that children who have many experiences in nature at a young age develop positive attitudes toward animals and the environment. For example, a survey of 1,030 urban Japanese residents found that collecting insects and plants outdoors was one of the most important factors for positive attitudes toward wild animals.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers may not be able to use insects directly in their classrooms, with instruction being remote for at least part of the school year. But educators can aim a computer camera at live large insects and use teleconferencing software to teach kids. We have, for example, successfully used Zoom to show a group of kids across Florida live large Eastern Hercules beetles, praying mantises and giant katydids.

What’s more, there are opportunities to use insects for learning outdoors, even if in colder climates there might not be year-round opportunities as we have in Florida.

Author Bios: Akito Y. Kawahara is Associate Professor and Curator of Insects, Florida Museum of Natural History and Megan Ennes is Assistant Curator of Museum Education both at the University of Florida

Amanda Markee a Researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida also contributed to this article