I have worked exclusively with PhD students for over a decade now. I have clocked up the 10,000 hours Malcolm Gladwell says you need to be an expert, so I hereby declare myself an expert in the problems of research education.

One sign that you can genuinely claim the title of ‘expert’ is when you start recognising, and instantly categorising, the problems you encounter into themes; a kind of ‘knowing in practice’ that is different to pure subject matter expertise. Some of the most common types of PhD problem are shitty supervisor(s), poor inital research design and not enough time left. Don’t even get me started on the variations of I can’t write this! problem I have seen over the years (in fact, I’m writing a whole book about this one with Shaun Lehmann and Katherine Firth, which should be out at the end of the year).

It’s fair to say I haven’t encountered a genuinely new problem in research education practice for years now – just more variations on the themes I already know. As an expert, I have a ‘repertoire’ of responses and actions that I can apply to any given situation. While most PhD problems have solutions – a pep talk, a whiteboard diagram, a book or suggestion for a new strategy – others don’t. The hardest, most intractable PhD problem-theme is how do I know when it’s enough?

This question gets asked about a whole range of things: the literature, the data collection, the word count, the ideas, the bibliography. How much is enough anyway? Frustratingly, there is no clear cut answer to the ‘enough’ dilemma because every student and thesis is different. When a problem is so contingent on circumstances, I can only offer partial answers – here are three of them, and a strategy for each.

How do I know when I have read enough?

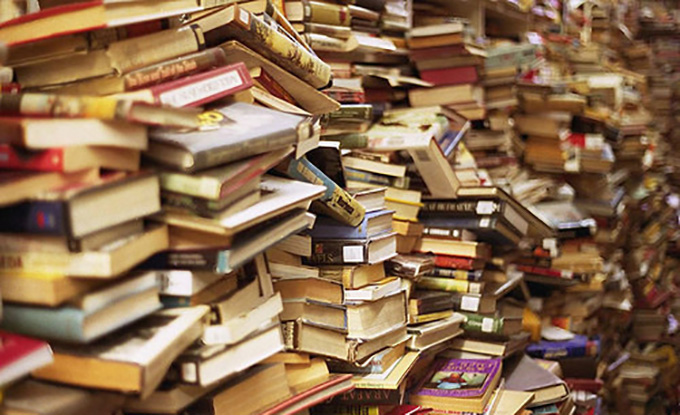

The only answer to this question is: “you won’t ever know”. Some people have compared the number of published papers each year to Mount Kilimanjaro, with the thin layer of snow on top being the papers that get downloaded more than twice. That’s an awful lot of excess academic production. There are mountains of literature on all kinds of topics. To avoid altitude sickness, you must try to set clear boundaries.

One way to start is to list the criteria that determine what is and isn’t relevant to your topic. For instance, some disciplines are fast moving, so you can use time as a criteria, then you only have to read back three years, five years or whatever seems relevant. Your topic might have a strong theme to guide your reading, for instance geographical location, historical period or type of participant. If you are doing a thesis on primary school aged students, for example, there’s probably very little point in reading literature on higher education. Methodology can be a strong way to determine you criteria. If you are doing a scientific study there might be no point referencing a qualitative study – and vice versa. There are, of course, exceptions, but mixing methodologies must always be done with care.

Whatever you do, you must account for it somewhere in the thesis – preferably in the literature review section. Some people develop their own, very specific criteria for political or theoretical reasons. I’ve met a couple of candidates who chose to only read and cite indigenous authors; some only to read and cite women writers. Such a strategy can carry risk, but I would like to think that a well argued reason for your choice should carry the day.

Exercise: try writing a short paragraph or two on your search strategy and the criteria you used so you can reflect on your choices and discuss them with your supervisor.

How do I know if this is original enough?

The originality question is a troubling one. While most people worry about not being original enough, or being scooped while they are doing the work, the opposite problem is possible and, perhaps, more common. Many academics promote multi-disciplinary work to solve this problem, which delivers on the originality, but can have unintended side effects. I have supervised at least one student who had a problem with being too original. She was mixing musicology and fuzzy logic. The mix was exciting, but everything about doing the thesis was very hard, particularly choosing examiners.

If you choose to do a multi-disciplinary thesis it is vitally important to have a strong idea of who the primary audience for the work is likely to be. My own thesis was about hand gestures in the architecture classroom, but I made sure to keep the focus on educators as the intended audience. This helped me take what I needed from anthropology and sociology, without getting too lost. The work would not have been considered original if I had constrained it to anthropology as there were plenty of people who had researched gesture, even amongst architecture students. But no-one had put it in context with the educational theories and practice of architecture, so I was able to find my niche.

Exercise: write a paragraph on the audience for your thesis. Who are they? What interests them about your topic? How will your thesis contribute to their knowledge in a unique way?

Have I written enough?

The glib (and largely correct) answer to this question is “when you have reached the word count specified by your university!”. Seriously though, we do know that many examiners prefer a shorter thesis, so finding the right length is what you might call a ‘wicked problem’. I encourage my candidates to write up to 80,000 words max, based on this literature. It’s not a hard and fast rule though, more like a rule of thumb. Recently I had a discussion with a colleague who was concerned that the theses in our school were too ‘thin’. His concerns were based on discussions with senior colleagues at conferences and seminars. We agreed there was more than a wiff of ‘young people these days!’, which might be a reaction to the trend to make theses shorter. Whatever the reason, there are clearly fashions and norms at play, like there is in anything. Your task is to try to ferret out what the fashions and norms in your discipline are and work out how you want to respond to them.

Exercise: ask as many senior people as you can about how long they like a thesis to be. If they can’t answer that question, try asking them what the most common length is. Try to gauge their reactions – do they seem to prefer the long ones or not? Keep good notes on the responses. When it comes time to make decisions, add up all the numbers you have and either average them out, or make a choice based on which numbers seemed to get most positive responses.

I hope that helps you – somewhat – with the enough problem. The only good thing I can say about these types of problems is, beware anyone who gives you a confident answer. An expert will know when to be cautious, being definitive about this kind of problem is a sign the person is a novice research education advisor. Do you have a problem that you have trouble getting a straight answer? I’d love to hear about them in the comments as they will probably make great blog fodder!