The Australian federal government’s proposed increase in the cost of studying humanities and communications degrees at Australian universities has stirred much debate. One aspect that should not be overlooked is that these changes will disproportionately affect women.

Under the proposed changes, student contributions for social science, communications and humanities (not including English and psychology) will increase by A$7,696 per year. That’s double their current cost.

Pushing women into STEM?

The government’s proposal has already been described as social engineering, given the government’s declared aim is to boost numbers of graduates in areas of expected employment growth, including teaching, nursing, agriculture, STEM and IT. The intention of lowering fees in these areas appears to be to attract more students to study these disciplines in preference to humanities.

If the idea is to encourage students to leave the humanities and study science instead, it’s a flawed approach. It would take a lot more than simply changing the cost of study to attract women to the field.

Women remain underrepresented at only 27% of the STEM workforce across all sectors, despite a range of initiatives designed to improve the balance.

For women, the real deterrent to studying STEM-related disciplines is related to employment outcomes and conditions, and challenges in even entering a STEM-based workforce. STEM women are likely to earn less than their male counterparts and also face poorer pay prospects than those who study humanities.

Perhaps more importantly, women in STEM have few examples of role models who clearly own the STEM space – reinforcing a notion that STEM-based work is male-dominated.

Pushing women away from humanities?

Increasing the costs of the humanities, then, might not push people into STEM or into areas such as nursing or education. But it might push them away from studying the humanities, and away from the vital work they do in a range of industries.

According to the federal government’s 2019 Graduate Outcomes Survey, 64.2% of humanities graduates were in a full-time position six months out from graduation. Many were employed in positions in public administration, education, business, health and science and technology – the very industries the proposed changes target. In these roles, they draw on skill sets acquired in their humanities degrees; skills that are remarkably similar to those Industry 4.0 capabilities employers are crying out for.

Every time I hear that #humanities BAs don’t lead to jobs, I wonder: Jobs for whom? #gender https://t.co/S5A0lN6vjP

— Allison Miller (@Cliopticon) May 16, 2016

Women earn less, and will pay more

Raising costs of studies in the humanities means these disciplines will shore up an effective reduction in government funding. In the longer term, women will bear the costs of this “saving”.

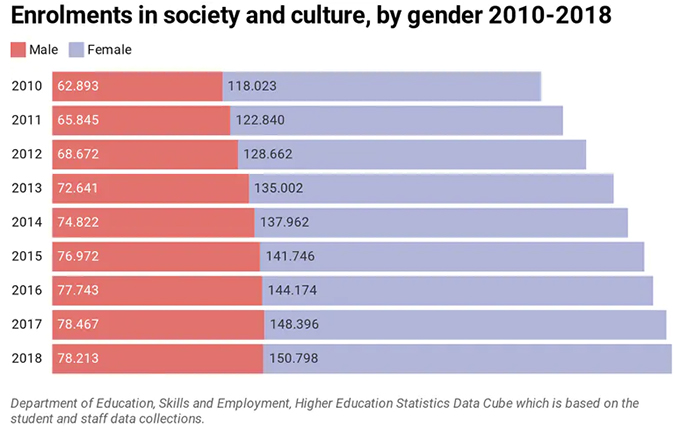

The reality is that humanities and social science disciplines attract more students than any other subject areas – the majority of whom are women. Women have consistently represented the bulk of enrolments in humanities and social science disciplines over the past ten years. In 2018, they accounted for two-thirds of enrolled students.

Consequently, under the government’s proposal, many women will pay more for their tuition and yet they are likely to earn less than men.

Gender roles continue to have an impact on the career trajectories and earning potential of women in Australia. Even though this gender pay gap is narrowing, primary child-caring roles and responsibilities — including taking time away from work, working part-time or leaving the workforce completely — are mainly assumed by, and expected of, women.

As a result, female university graduates earn, on average, 27% less than men over their careers. This means women take longer to pay off their student debt.

The Australian university debt scheme is often praised because it doesn’t incur interest rates or have a timeline for repayment. However, the tangible effects of a larger debt mean women humanities graduates will be in debt for longer. They will have less disposable income for longer. And they will have limited capacity to invest money, and so expand income, for longer.

#humanities subjects are dominated by women. On average, women take longer than men to pay off their HELP debt due to the #gender pay gap and childbearing. By doubling the cost of Arts Degrees, the government is further entrenching the financial inequality between men and women.

— Sarah Copland (@sas_yvonne) June 19, 2020

The argument that programs that traditionally attract more women – such as nursing and education – will be made cheaper, and therefore more accessible, doesn’t stack up either. Because there are more women in humanities-based degrees than other programs, the proposed changes still mean women will bear the brunt of these increases. Or be forced out of higher education if their calling isn’t teaching or nursing.

Making higher education unaffordable for women just adds to a raft of conditions that already ensure inequalities.

Author Bios: Deanne Gannaway is a Senior Lecturer in Higher Education and Grace Dunn is a Research Assistant in the Humanities and Social Sciences both at The University of Queensland