In order for performance based funding (PBF) to work, institutions must be incentivized to adhere to the model, and improve their results on key metrics. In Michigan, a relatively small share of funding that only applies to annual budget increases does little to hold institutions accountable for several state goals. What’s more, the PBF formula is quite complicated, especially to allocate a sum that is traditionally below 3.0% of the entire allocation to institutions. These factors weaken the model’s effectiveness and have led some institutions in the state to intentionally forgo extra state support.

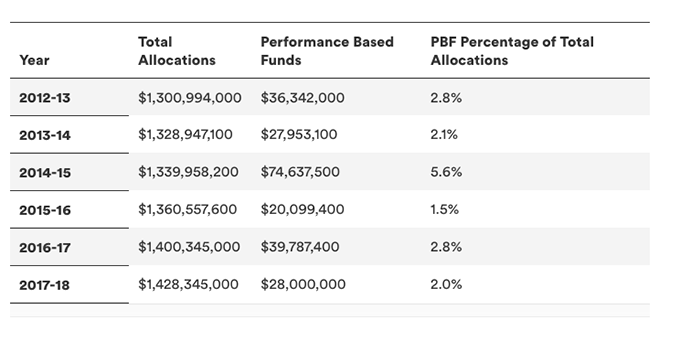

Michigan first implemented PBF for four-year institutions in the 2012-13 school year. Under this model, funding increases over the previous fiscal year’s budget are partially distributed according to an institution’s performance on several established metrics . But the formula also dictates that half of any annual budget increase will be distributed to institutions based on their share of higher education funds from the 2010-11 academic year. By earmarking an equal portion of any higher education budget increase for automatic bumps tied to historical funding shares, Michigan lawmakers have left relatively little to fuel their PBF system.

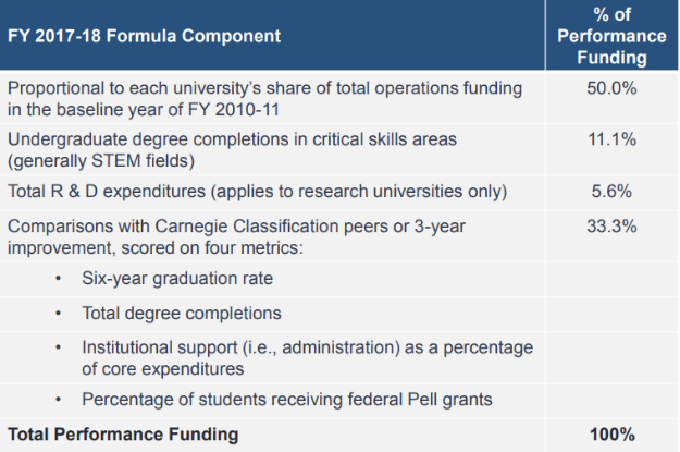

For example, in July 2017, the legislature passed a budget calling for an increase of $28 million over the previous fiscal year. Since Western Michigan University received 7.7% of the state’s higher education allocation in the 2010-11 school year, it would continue to receive 7.7% of any new funds (See Figure 1). In dollar amounts, 7.7% of $14 million (half of the total $28 million budget increase) totals just $1.078 million. Similarly, 11.1% of performance funds are allocated to institutions based on their share of STEM degrees produced in the state. Since Michigan State produced about 17.57% of the state’s STEM graduates, for example, they receive 17.57% of these funds. Of the remaining funds, 5.6% is available only to research institutions, while 33.3% is allocated based on graduation rates, total completions, percentage of Pell eligible students enrolled, and administrative expenses as a percentage of total expenditures. Performance on these metrics are compared to an institution’s national peers using a taxonomy of institutions known as the Carnegie Classification.

Before institutions are eligible to receive PBF from the state, however, they must meet each of four additional criteria. They must limit any tuition increases to $475 or 3.8%, whichever is greater, and engage in at least three transfer agreements with community colleges. Additionally, they must not penalize applicants for college credit earned in high school and provide data to several state-level sources.

Funds allocated to institutions vary by amount and percentage of total funds. At the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, the state’s allocation was about $315 million for the 2017-18 academic year, whereas total revenue to the institution was over $8 billion. Performance funding from the state totaled just $5,950,100 or 0.07% of the institution’s total revenues. On the other hand, Northern Michigan University receives $47,137,400 from the state, of which $858,200 is performance based. Compared to NMU’s revenue of $110,049,560, performance funding constitutes slightly more than the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, but it’s still a paltry 0.78% of the university’s total revenue..

With such a small portion of operating funds coming from performance related metrics, it is hard to envision institutions placing much effort on improving those results. Between the 2012-13 school year (the year PBF was introduced) and 2015-16 school year (the most recent data), Northern Michigan’s total completers, six-year graduation rates, and percentage of students receiving Pell grants have actually decreased – yet they still receive PBF from the state, because institutions are scored against their Carnegie Classification peers, rather than their own progress. Over the same time frame, the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor’s completers have increased by 2%, and graduation rates and Pell percent has increased by 1%. In this context, performance based funding does not appear to incentivize institutions to significantly improve their outcomes.

In some cases, institutions have decided to violate the conditions for receiving performance based funds. For the 2015-16 academic year, Eastern Michigan University and Oakland University decided to raise their average tuition by 7.78% and 8.48%, respectively. As a result, Eastern Michigan lost out on just over $1 million and Oakland $1.2 million in performance based funding. However, Oakland’s enrollment grewfrom 12,407 to 12,836 students, and Eastern Michigan’s enrollment remained stagnant (12,938 to 12,894). Under these conditions, it is not out of the question that institutions could increase revenues by raising tuition and forgoing performance based funding. These are the only examples of institutions choosing not to participate in the funding model since its introduction, but a strong performance based funding model keeps all institutions engaged on an annual basis, a trait that Michigan’s model does not have.

What’s more, performance based funding in Michigan only applies if the state passes a budget greater than the year before. If the state does not increase higher education allocations, then no funds are distributed on performance metrics. Fortunately, the state has increased higher education appropriations each year since the model has been introduced, but without a guarantee of annual evaluation on these metrics, institutions are less inclined to adhere to the prescribed metrics. Improving these metrics can often mean new academic programs, increased faculty and staff, and enhanced services and facilities for students, all costly endeavors. If institutions do not anticipate a worthwhile return on their investments in increased state funds, pursuing changes will not occur.

While many iterations of PBF models have been developed or implemented across the country, Michigan’s plan fails to incorporate several widely recognized best practices. The consequences of this can be clearly seen when comparing Tennessee’s plan, widely considered to be an exemplar model, with Michigan’s. In Tennessee, legislators committed a substantial portion of the higher education budget to performance funding, and sought buy-in from campus administrators by allowing them to choose the targets by which their institution would be measured. Additionally, the state displayed its commitment to improving certain metrics by introducing the Drive to 55, Tennessee Promise, and Tennessee Reconnect initiatives in conjunction with the model. In Michigan, the amount of funding available has led institutions to not participate at times, and it has not signalled a clear commitment to state goals. Neither has Michigan complemented PBF with other statewide programs that align with the performance metrics.

Without guaranteed funding increases, concrete performance metrics, or other state programs supporting the performance funding model, Michigan’s performance based funding system will struggle to hold institutions accountable for improving student outcomes. To remedy these concerns with the funding model, Michigan should increase the amount of funds diverted to institutions based on performance metrics, measure institutions’ performance based on their own year-over-year improvements and not on their peers’, and create other statewide initiatives that complement the model. If this occurs, institutions in Michigan will be incentivized to improve their metrics, and both students and the state will benefit.