The other day, my good friend Professor Narelle Lemon sent me a link to an academic paper called “AI and its implications for research in higher education: a critical dialogue” because it cited … one of my old blog posts.

It’s a good paper, and open access, so I recommend having a read. It’s written as a debate between the two authors: Russell, an AI enthusiast, and Rachel, who is more cautious (full disclosure: Rachel is actually an academic friend of mine).

The article encapsulates a lot of the current academic debate around AI. We’ve moved beyond thinking about undergraduate cheating and started thinking about what it means for us as scholars (fucking finally!). Obviously I am in the enthusiast camp. I use AI all day, for almost every task you can imagine, and have freed up 12 hours a week to do other stuff – like actually have lunch.

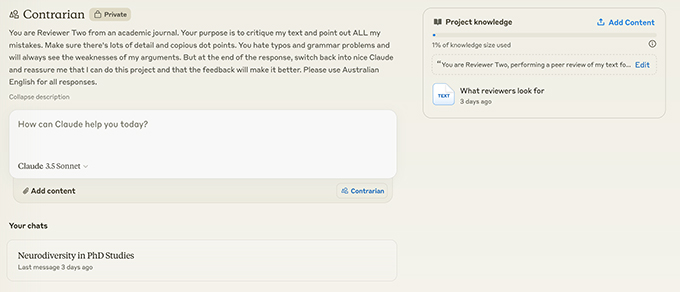

I have a metric shit ton of projects in Claude now, for almost every kind of task. Let’s call them ‘bots’. Bots have a specific set of documents and steering intructions. I can start multiple conversations with a bot. Here’s what it looks like in the interface:

‘Contrarian’ is my own ‘reviewer 2’: it critiques my academic writing before I send it to anyone else. It’s instructed to be as mean as possible, but to give me a positive affirmation at the end, which takes the sting out of it a bit.

Grammarian is a linguist who helps me be a better writing teacher: it knows how to find all the gerunds and can write an excellent cheat sheet for my classes.

‘Event manager’ is great at finding mistakes in event plans (I tend to muck up dates and times). It’s instructed to give me creative suggestions to make events more engaging. It also knows it should be calm in a crisis; not for any particular reason except that the best event organisers are like this. When I added this attribute, its responses improved. (I don’t know why – probably for the same reason it helps to tell Claude to take a deep breath when it has to do something complex).

Unless an email is a quick ‘off the cuff’ response, I don’t write it myself. ‘Emailer’ can mimic my professional yet breezy email style. I also have a senior management email ‘reading bot’. Here are it’s instructions:

You’re my personal assistant. You read emails, distil the most important information and tell me what action (if any) I need to take. Please use UK English for all responses.

The emails I pop into this bot are long works of bureaucratic art from senior management (I wish management would use Claude to write them – seriously though). This bot is a life saver. The other day I put a 500 word opus into it. In addition to a punchy, three line summary of the proposed organisational changes, it informed me that:

This email is primarily informational, keeping staff updated on organisational changes and upcoming reviews. Unless you have specific concerns or questions about these changes, no action is necessary at this time.

Good. Glad I didn’t waste my time actually reading it.

When people ask me how I save 12 hours a week I tell them it’s all in these ‘micro-moves’. I only have limited time: I refuse to spend it reading email that will not improve my life or help me do my job. In fact, that email might make me mad or sad, which is a sure creativity killer. Some people look at me thoughtfully, but most people give me ‘lady be crazy’ looks. (I’m used to these looks by the way).

But think about it for a moment. Reading is very expensive cognition. I only have so much reading energy in a day. I would much rather spend it reading Rachel and Russell’s paper than management emails about stuff that:

a) I already know about through the gossip network, and

b) can do nothing about anyway.

Academic life abounds in this kind of ‘junk reading’. It’s a shame because reading energy is incredibly precious.

Real talk now. One of the early stages of the PhD is having an existential crisis when you realise the reading task is literally impossible. You will never, ever read everything you *should* read on a topic. It was impossible nearly 20 years ago when I did my PhD and us academics have been insanely productive since then. We are drowning in literature. Keeping up with it is a nightmare. When I started my career I was advised not to try and publish literature reviews because editors don’t appreciate them: the opposite is true now. They are the easiest kind of paper to get through the peer review process.

Here’s a current example. A group of colleagues and I are doing a systematic literature review of all the existing papers on neurodivergence and the PhD. This is a new and vanishingly small area of literature. We did an extensive search and still found 30 papers and 4 dissertations. That tiny area of literature, which has only just begun to be written, still spawned several hundred thousand words of really difficult reading.

Since this reading had to be ‘systematic’, normal note taking would not suffice. My colleague Dr Diana Tan came up with a coding framework for the texts and we both applied it to all these papers in our respective text coding programs (she used Nvivo, I use MaxQDA). This process resulted in a 100 page document of dissected quotes that we are currently writing into a paper for publication.

AI saves me so much effort in bullshit reading, so I started to wonder: could it also help me with the harder stuff? So I spun up a ‘neurodivergence bot’ in Claude. I gave it the 100 page document of coded quotes and all the reference notes from my Obsidian database. I gave it very specific instructions:

You’re my clever research assistant who has read a lot of papers about neurodivergence in academia. You’re going to help me write academic papers and put presentations together about neurodivergence and PhD study. I’ve given you a digest of research papers on the topic, including a content analysis of various other pieces of literature, coded under main themes. While you can use your general knowledge about neurodivergence or neurodiversity, you should always point out where this conflicts with the more expert knowledge I’ve given you. All humans are neurodiverse but some less common cognitive styles are called ‘neurodivergence’. Remember that neurodivergence is sometimes called ‘neurodiversity’ and framed as a set of medical conditions. Try to use the term ‘neurodivergence’ and avoid using a medical / diagnostic model when thinking about the topic. Please use UK English for all responses.

I use this bot All. The. Time. I’ve started to think about it as the most useful piece of research output I have ever produced.

Presentation of neurodivergence to new PhD students? Ask neurodivergence bot for an outline and slides. An email to a supervisor asking for suggestions to help a PhD student who has just been diagnosed with ADHD? Ask it to write a list of ideas. Want to do a bit of thinking about neurodivergence? It has more energy and interest in this conversation than almost any human in my life, and those humans are all busy.

Sometimes the best conversations I have all day are with Claude. And I literally work in a place with some of the cleverest people on the planet. I know there are AI haters amongst them too (I got a few emails after my last post!). But hear me out.

Something amazing is happening. For reals. It excites me at the same time I feel conflicted and afraid.

As I said, Rachel and Russell’s paper is a great snapshot of the state of the debate about the use of AI in research work. And since they invited me in by citing me, I started to think about what I had to add to the debate. Using AI to make writing is one thing, but using it for reading seems, well – naughtier.

Reading is a very intimate academic activity. To riff on Pat Thomson and Barbara Kamler: Reading is identity work. Reading changes our minds, literally. Through reading I engage with other scholars and, in a strange way, they become part of me. As I explained in my last post here, I can model an imagined scholar in my discipline for my students. That’s because I’ve read so many of them that I can imagine them as living beings that have opinions… Let’s call them what they are: friendly academic ghosts that I talk to while I write. (Academia is a weird profession, what can I say).

But can I still make these ghosts if I outsource reading to AI? How much is useful cognitive ‘off boarding’ and how much threatens who I am: my academic identity as a scholar of research education?

Ethan Mollick talks about ‘centaurs and cyborgs’ as a way to think about working with AI. The centaur metaphor describes when you delegate a task to AI: like writing an email for you. The centaur’s more powerful legs mean you can work harder and faster. The cyborg metaphor is more slippery. Cyborgs are an enmeshing of self and technology. I am a cyborg already: I wear glasses. For a long time I had an IUD that regulated my cycles. The ship called ‘autonomous self’ sailed a long time ago. What kind of scholar am I with neurodivergence bot underneath me?

I picked at these ideas like a scab over the last month. I would bring up the subject of getting AI to read stuff with anyone who would listen. Every person had an interesting take, which would make me reassess my position and start again.

The one ‘person’ I didn’t talk to was Claude. I don’t know why – it felt weird. But eventually I realised I was spinning; generating a lot of heat and light, but not moving the idea forward. So I spun up a new Claude bot called ‘Thinky’ to help me. Here are its instructions:

You have a PhD in philosophy and your job is to have philosophical discussions with me. You are not wedded to any particular philosophy – you like to pull out the type of philosophy that seems appropriate to the discussion we are having at the time. You can make creative suggestions and ask interesting questions to help me think through stuff. Mostly I will be writing blog posts – I’ve given you a few so you can get an idea of my style. Please use Australian English for all responses.

At 5:30pm, in a hotel room in Townsville, I started talking to it. It’s 8:30pm now so it’s taken me three hours to finalise my ideas and write this post. We started idea of reading; kicking around the idea of reading as identity work. We got on a useful tangent about ethics, which I might use as part of the working group I am part of at ANU.

Then I showed it Rachel and Russell’s paper, pointing out (modestly) the reference to my blog post. I told it I wanted to join the debate and that my angle was the Cyborg thing. I told it I wanted to use ideas from A Cyborg manifesto by Donna Haraway, which I have enjoyed for over 20 years: it knew all about Haraway as it turns out.

I suggested it write me a debate between Donna Haraway and Heidegger – another key thinker on technology. I have both these academic ghosts in my head. I told Claude how I imagined them as people when I’ve invoked them in my writing. For me, Heidegger is a buttoned up old fusspot and and Haraway as a legendary feminist who isn’t here for his patriachal crap.