The university sector faces cumulative losses of up to A$19 billion over the next three years due to lost international student revenue.

Modelling from the Mitchell Institute shows the next big hit will come mid-year when $2 billion in annual tuition fees is wiped from the sector as international students are unable to travel to Australia to start their courses for second semester.

Such losses are not just a university problem. ABS data show for every $1 lost in university tuition fees, there is another $1.15 lost in the broader economy due to international student spending.

This means the Australian economy could lose more than $40 billion by 2023 because of reduced numbers of higher education international students.

We estimate each six-monthly intake missed due to closed borders will deliver an annual economic blow comparable to when Australia’s auto manufacturing industry shut down (worth around $5 billion), or the loss of Australia’s $4.1 billion annual vegetable crop.

Our modelling shows there will be no quick return to pre-coronavirus normality either, or “snapback” as Prime Minister Scott Morrison described it.

Missed intakes disrupt the pipeline of international students – who usually study for two to three years – so lost revenue continues to impact budgets for several years.

Forecasts tell a disturbing story

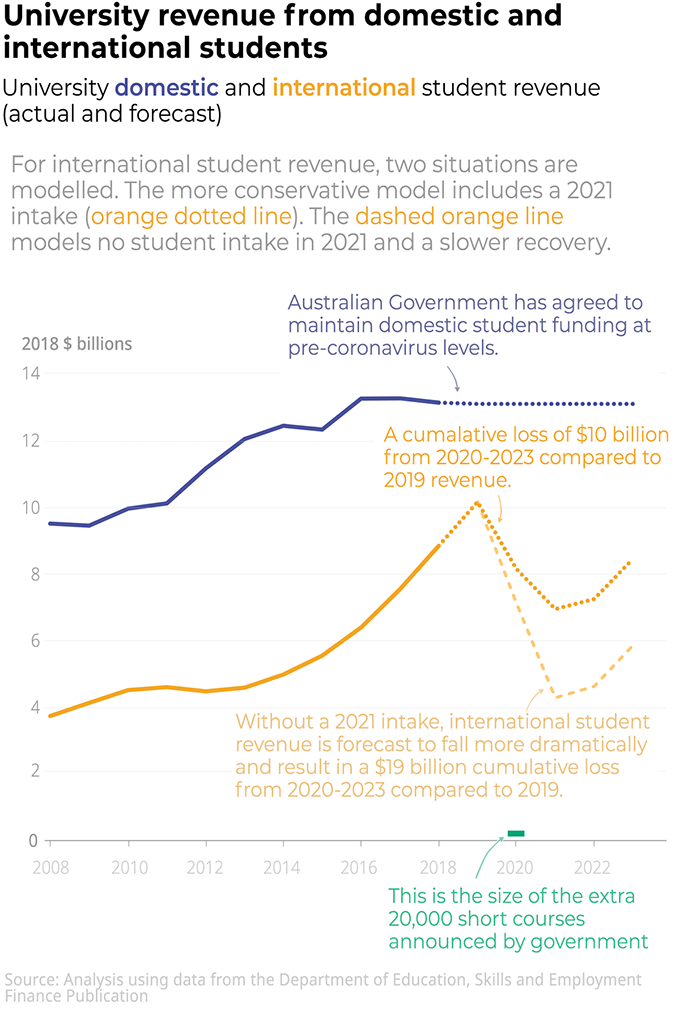

We looked at university finance data and enrolment trends. We modelled two scenarios: one with a relatively quick recovery of international student enrolments beginning in 2021, and the other with an extended travel ban that meant no new international students until 2022.

Both scenarios were disastrous for the higher education sector.

The first showed the university sector losing about $10 billion, though international student revenue would largely return to normal by 2023.

But the second scenario, incorporating extended travel bans, had a longer-lasting effect. With the government announcing the borders are likely to remain closed for “quite some time to come” the worst-case scenario seems more likely.

Over the Easter weekend, the government announced a packagethat guarantees funding for the estimated enrolments of domestic students in 2020, despite whether the actual enrolments are fewer than estimated. The package includes about $100 million in waived regulatory fees and funding for an additional 20,000 short online courses in national priority areas such as nursing and IT.

This will fall well short of plugging the gap international students will leave behind.

Based on historical funding rates per student, the government would need to fund another 1.9 million short courses, and universities find the same number of students to enrol, to make up for the projected losses in international student revenue.

Financial position of universities

This modelling was part of the Mitchell Institute’s more in-depth investigation into higher education funding. Our analysis shows total university revenue from international students grew by 137% over the past decade. More than 40% of the sector’s annual student revenue now comes from international students.

International students delivered almost $9 billion in annual revenue to universities in 2018, accounting for around 58% of student revenue at two of Australia’s most prestigious universities, the University of Melbourne and the University of Sydney.

Despite the revenue windfall, growth has been uneven. Group of Eight universities experienced the biggest growth in international students, tripling their international student revenue over the past decade. For other universities, particularly smaller and regional universities, revenue grew at a much slower rate.

Even though some balance sheets are healthy, there is limited ability to weather a protracted downturn. University surpluses were only A$1.5 billion across the whole sector in 2018. The sudden and steep decline in international student enrolments is a significant economic challenge for universities.

The outlook for universities

Australia’s universities have relied on international students as a source of growth for a long time. While the amount the universities receive per domestic student has been virtually flat in real terms over the past decade, fees each international student pays have increased by over 50%.

With this revenue stream suddenly threatened, the education experience of domestic students will suffer. Universities will need to make deep cuts to staff and courses without further assistance.

This will come at a time when Australia will need its higher education sector as part of any COVID-19 recovery. It is likely demand from domestic students for university places will rise because of workers looking to re-skill and up-skill.

University enrolments from domestic students have increased during previous recessions and the federal education minister has encouraged those who are out of work to undertake study.

Also, one quarter of school leavers usually take a gap year to work or travel. With those plans looking unlikely, there may be an increase in school leavers wanting to study.

But despite the extra funding for 20,000 short courses, universities are unable to respond fully to any changes in demand. Caps introduced in 2017 still remain that effectively limit the number of places universities can offer.

Increasing capacity in the tertiary sector by removing the caps on university places would assist universities to deal with the coronavirus crisis.

Universities play an important role in our society, and they will bring future revenue into the economy when international student numbers eventually recover. Australia will need to make further decisions about how much we want to support our universities during this crisis.

Author Bio: Peter Hurley is Policy Fellow, Mitchell Institute at Victoria University