The Australian government recently announced it will resume granting visas to international students in a move to push forward with international education. This means when borders reopen, many students will already have visas to come to Australia.

Current and new students, studying online with an Australian university, while overseas due to COVID-19, will also be able to count that study towards their graduate working visa in Australia.

The temporary graduate visa (subclass 485) allows international students to stay in Australia after they graduate for two to four years to gain work experience.

This aligns post study work rights policies in Australia on par with those of Canada (in place in March) and the United Kingdom (in place in June).

#BREAKING Australian government announces visa changes for international students @SBSNews pic.twitter.com/D5kVnuSkX3

— Catalina Florez (@florezcata) July 20, 2020

Australia’s reputation may have been tarnished by the federal government’s exclusion of international students and graduates from its JobKeeper subsidy scheme. The visa changes now attempt to signal to prospective students Australia is an open and welcoming destination.

But the global headwinds facing the international education sector underline that any policy shifts in Australia need to go beyond simply matching what is already on offer in leading study destinations.

Deferring students

Australia must not only attract new students but also convince deferring students to come back.

New data show a substantial increase in the number of students deferring their studies to a later date, but a minor increase in enrolment cancellations.

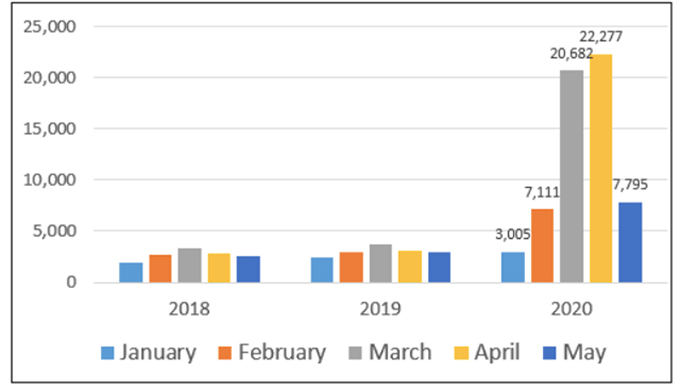

There were 60,870 deferments for the year to May 2020, 45,597 more than in the same period in 2019 (15,273). Deferments were in the form of either a delayed commencement or a temporary suspension of an existing enrolment.

The number of international students who deferred their enrolment, month by month, across all sectors (including university, VET and schools). Australian Government, Department of Education, Skills and Employment, Research Snapshot July 2020 (Screenshot)

By May 31 2020, 20% (121,472) of all primary student visa holders (606,485) were outside Australia.

Post-study work is a major incentive …

We conducted a survey in 2018-19 involving 1,156 international graduates. Most of them (76%) said Australia’s temporary graduate visa played a role in their decision to study in Australia.

But the sustainability of Australia’s international education will need to address issues relating to both post-study work visa arrangements and employment outcomes for international students after graduating.

Many employers lack understanding of the visa, prefer applicants with permanent residency or hold misconceptions of complex paperwork or sponsorship involved. The chance to gain work experience in their field during their study and after they graduate is limited for many international students.

The UK, in its immigration point system, set a lower salary threshold requirement for international students coming off a post-study visa and aiming for a skilled visa. This was to address the high salary threshold many employers were unable to afford, which was one of the impediments for international graduates in securing employment in the UK.

Addressing existing barriers will enhance Australia’s reputation as a destination for quality education and a positive post study work experience.

The government and universities must also offer extended support to alumni stranded onshore, who may have been working here on their graduate visa but lost their job.

…especially for students from India

Indian students are most affected by the access to a post-study work visa. In our above-mentioned survey, 82% of Indian students considered the visa an important factor in their decision to choose Australia, compared to the average rate of 74% for non-Indian international students.

In September 2019, the United Kingdom announced a reintroduction of their two year post-study work visa in response to the decline in international enrolments.

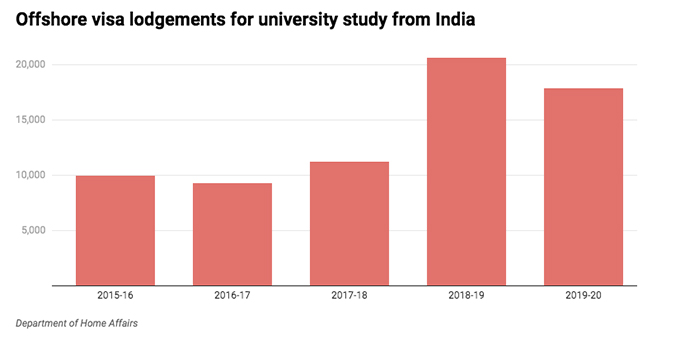

In the third quarter of 2019, the UK and Australia were equally searched as study destinations from India — at 16.2% and 16.8% respectively. But the UK’s September announcement had an immediate effect. According to IDP Connect data search results increased by 47% to the UK, and decreased by 15% to Australia.

According to internal university data, some universities in the UK reached their 2020 international enrolment caps as early as November 2019. Meanwhile, Indian offshore visa lodgements for Australia dropped by 13.5% this fiscal year.

In July, the Australian government announced it will offer current and future Hong Kong international students an additional five-year post-study work visa with a pathway to permanent residency. Only two weeks after that, there was a massive increase in interest from Hong Kong students wanting to study in Australia.

What else matters to international students?

In addition to tensions between China and Australia, the health and economic impact of COVID-19 will affect the financial capability of future international students to study overseas — as well as whether borders continue to be closed to countries.

Other factors determining how international education recovers will include how host countries support international students (on and offshore) during and in the aftermath of COVID-19.

A holistic, well-coordinated, and flexible approach is crucial in determining both immediate international student recovery and long-lasting destination attraction.

Author Bios: Ly Tran is a Professor and ARC Future Fellow and George Tan is a Research Fellow both at Charles Darwin University