For the Golden State of California, 1960 was a golden year: It was a time of rapid development, when the state chose to use its tax revenues to fund magnificent freeways and other infrastructure.

Part of this massive development was a system of public higher education – a model that put California center stage in the American imagination.

From my perspective as a social historian who started high school in Southern California in 1961 and then entered graduate school at the University of California Berkeley in 1969, the story of higher education in California over the past 60 years has been a fantastic voyage – albeit with detours and delays.

Start of the dream

California’s higher education prospects of 1960 were built on a distinctive historical foundation. The idea that the state’s colleges and universities could – and should – be the source of an informed, responsible citizenry and state leadership had been established by legislators and voters by World War I.

Robert Gordon Sproul, president of the University of California, who served from 1930 to 1958, built on this early vision. He set up six campuses statewide as part of a creation of a multi-campus system to meet California’s growing demand for higher education.

After World War II, as returning veterans headed back to school the demand continued to grow: Enrollments in universities increased by as much as 50 percent. At the same time, the number of high school graduates went up as well. The number of campuses needed to be further increased.

The rapid growth in potential students coinciding with the crazy quilt of a large number of public and private institutions led to turf wars. The foremost problem was a contentious rivalry between the University of California system and other state-funded higher education institutions. Both were in competition for funding and students.

The dream years

When Clark Kerr was named president of the University of California system in 1958, he sought to end the chaos of the statewide academic “guerrilla warfare.” Kerr was an economist who had served for seven years as chancellor of the university’s flagship campus at Berkeley.

With Kerr’s efforts higher education became part of the California dream. In 1960 the state legislature passed the Donahoe Act. This legislation included a 246-page report, “A Master Plan for Higher Education in California, 1960-1975.”

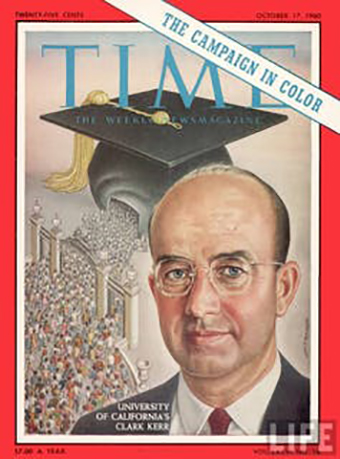

President Clark Kerr on the cover of Time magazine. Dale Winling, CC BY-NC

To reduce chaos, missions were clearly defined for each institutional segment: University of California was to admit the top 12.5 percent of high school graduates, and the California State University and Colleges would draw from the top 33 percent of remaining high school graduates. The others could enroll in junior colleges, later renamed “community colleges.” These junior colleges provided associate degree programs, and their graduates could apply for transfer to the four-year colleges.

The plan gained national attention. On Oct. 17, 1960, Time magazine featured Clark Kerr on its cover as the “Master Planner.”

A distinctive feature of the California master plan was that the state’s private colleges and universities (also known as “independent colleges and universities”) too were included in this public policy, the rationale being that distinguished private colleges and universities such as Stanford, University of Southern California, California Institute of Technology and Claremont Colleges were a unique resource to the state. Their alumni, as skilled professionals and leaders, contributed to the state’s development. These institutions were also major employers within their counties and communities.

Affordable and a place of excellence

What is particularly important to note is that the California dream of higher education combined access to higher education with affordability and choice. Until then, the City University of New York (CUNY) had been the only major public higher education system that had a tradition of not charging tuition. But the New York policy for its CUNY segment did not apply to New York’s other public institutions, such as the State University of New York (SUNY).

In contrast, the new California policy of no tuition was extended to all public colleges and universities statewide. Furthermore, the master plan promoted state-funded student scholarships through a state agency created in 1955, the California Student Aid Commission.

California came to provide a high quality of education – the best in the country. A 1966 report by the American Council on Education (based on data collected in 1964) shows that University of California, Berkeley was the top university at the time in America for overall quality in graduate education.

Excellence was encouraged and nurtured. Between 1939 and 1968, 12 professors at UC Berkeley had received the Nobel Prize, the highest number at any university.

Resources were made available for the realization of the dream. As part of passing the Donahoe Act in 1960, the California state government approved US$1 billion (equivalent to about $10 billion in 2017) in funding for higher education facilities. Central to its growth was an expansion of campuses. Between 1964 and 1965 the University of California built three new campuses – at San Diego, Irvine and Santa Cruz.

University of California, Irvine, 1966. Orange County Archives

Inflation, tuition, loans

By 1967, however, the master plan was encountering problems – it was expensive and increasingly seemed not sustainable.

In addressing citizen groups, state Senator George Deukmejian voiced Republican concerns about higher education. According to a front-page story in The Whittier Daily News on October 14, 1967, Deukmejian argued in favor of adding a tuition charge for University of California students and endorsed Governor Ronald Reagan’s new “equal education plan.” The plan called for a modest tuition of $250 per year (worth approximately $2,500 today) for the university and $80 per year in the state colleges (equivalent to $800 per year today).

The Republican reform plan included grants or loans to those who could not afford the modest tuition. He noted that half of the enrolled students came from relatively affluent families. Only about 12 percent came from modest-income families earning $6,000 year or less (about $60,000 today).

When Deukmejian took office as governor in 1983, he continued to impose tuition charges on students at the University of California and other state colleges.

The realities today

Today, California’s higher education system struggles with budget cuts and an uncertain future. The reasons are many.

The percentage of Californians seeking to go to college gradually increased, and so did the overall number of high school graduates. Consequently, the expansion in college enrollments over a little more than a half-century was incredibly large.

In 1960, for example, the total enrollment for all institutions in the state was 234,000. By 2015 University of California enrolled 253,000 students at 10 campuses, California State University enrolled 395,000 students at 16 campuses, and the community colleges enrolled 1,138,000 at 113 campuses. This was a seven-fold enrollment increase since 1960 – the most among all states in the nation.

In contrast to 1960, student fees and tuition increased while state general fund subsidies per student tapered. In 2015, tuition charges at UC were $12,240, a tenfold increase over 1960.

During the past four decades, California’s public colleges and universities have endured lean budgets. The start of this came about in 1978, when passage of Proposition 13 placed a ceiling on property taxes, which, among others, had helped provide revenues to the state for meeting expenditures for public education.

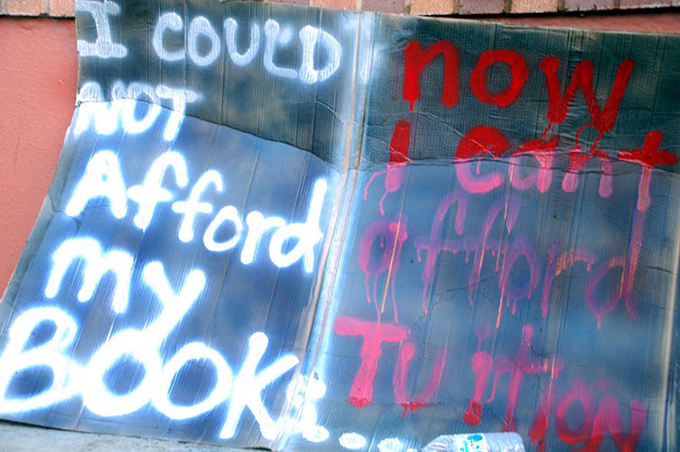

Signs from students who came together from all California university campuses to protest against tuition hikes in November 2009. Sarah Smith

Today there are concerns that the public universities, as a result of budget cuts, are soon going to be “public no more.” As education scholar Brendan Cantwell notes, even the preeminent research university, Berkeley, has been hit by budget cuts. At the same time, the state’s outstanding private colleges and universities have soared in terms of academic standards, selective admissions, tuition revenues, new construction and federal research grants.

The master plan has struggled to keep up. It has gone through many reviews and revisions, the latest of which, in 2017, emphasized improving access and affordability.

But the convergence of these trends, combined with fluctuations in the state economy and tax revenues, has turned the Californian dream of higher education into an American dilemma.

California dreaming: Questions ahead

In truth, the 1960 Master Plan was hardly a panacea for making a college education available to all. It has, however, been an enduring document with its essential principles and goals.

To go from the ideal to the real requires attention to the context of a new era.

In looking ahead, California’s higher education system faces the challenge that president of the Ford Foundation, John Gardner, a Californian, aptly posed in 1961:

“Can we be equal and excellent, too?”

Author Bio: John R. Thelin is a University Research Professor at the University of Kentucky