In the past few days, I have lost count of the times I’ve heard politicians and others say that sexual comments, coercion or even acts of force were acceptable 15, 20 or 25 years ago, but the “goalposts have moved” and that times have changed. Sexual abuse has never been acceptable. But with many victims silenced, it has certainly been kept a private shame rather than the public concern it should always have been.

It has infected the entertainment industry and even parliament. The stories emerging now have rightly shocked Britain – and led women and male victims to call out harassment and inappropriate behaviour under the #metoo banner.

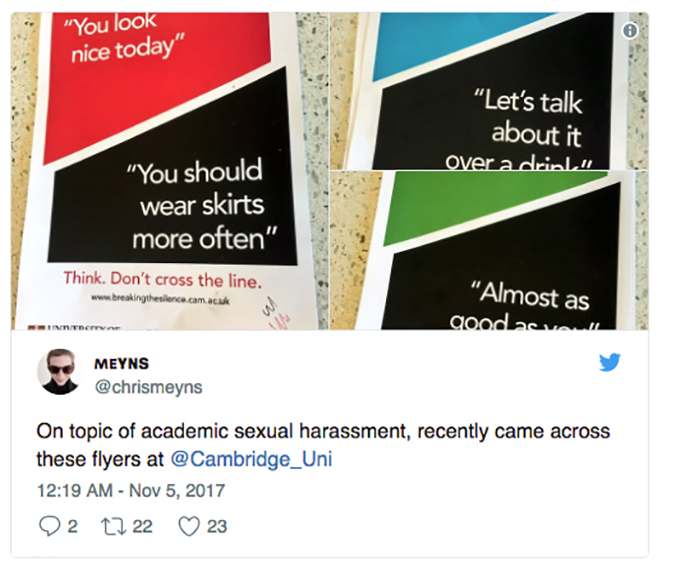

This is an issue facing all of society, not just the people who have been in the headlines. Cambridge University recently launched a campaigncalling for an end to this silence. Why now?

Some years ago I was asked to meet some students for an urgent meeting. Two of them told me that they had been sexually assaulted by fellow students at a university event. They said that they did not want to go to the police, but wanted the university to do something about it. But what could the university do? I told them that we could do nothing.

All universities in the UK at the time subscribed to guidance derived from the Zellick report, published in October 1994, which said that allegations of rape and sexual assault were matters for the police and not for universities – even if the student victim wanted the university to do something.

As Zellick said: “If the victim will not report the matter to the police … the university should not use its internal procedures.” The guidance told us universities were not equipped to deal with such cases. But this left victims with only two choices – go to the police or keep quiet.

Without a mandate to investigate or respond, many universities did not develop proper case handling. It was many years until it became a sector standard to have disciplinary code of conduct for harassment or sexual assault.

But that was then. Things are, thankfully, different now.

Ringing the changes

A year ago, on November 8 2016, Universities UK published Changing the Culture. This report considered violence against women, harassment and hate crime against university students. It also reconsidered the Zellick report and concluded that it was outdated and its guidance inappropriate. I was part of the particular task force that reconsidered the report and then rejected it. This was a vital step in universities accepting responsibility for their students who have been the victims of sexual misconduct.

One year on, at Cambridge we have made significant strides in responding to sexual misconduct. In October we launched Breaking the Silence, a campaign banner under which there are various initiatives to respond to sexual misconduct and abuse including a complaints procedure, anonymous reporting, consent workshops and sports codes of conduct.

Culture of respect

Like many universities, we are told we should both do more and that we are are doing too much, with the risk of undermining criminal processes. Universities are therefore walking a tightrope, where we have to ensure that all students who study (and staff who teach and do research) feel safe and confident that any abuse will be taken seriously. At the same time we need to ensure that our processes are fair. We will take all allegations seriously, but we must ensure that they are investigated carefully and objectively and that our responses are appropriate to all.

Over the past three years the university sector has done a lot, but there is more to be done. We need to work ever harder to ensure that there is a change in culture and that we are a beacon for the rest of society as to what is acceptable conduct, based on respect.

Three years ago I told those two students that there was nothing the university could do. Today I can tell them that if they come forward with complaints of sexual misconduct they will be guided and supported to determine what is right for them. For some that will be to go to the police, for others it will be to rely on the university to identify an appropriate response. But whatever route they wish to adopt, all students, no matter where they are studying, need to be empowered and to have confidence and trust so that they can break their silence.

The headlines we’ve read are shocking, but if we can turn righteous indignation into change, we will have gained something from these appalling stories – a society where no one has to say #metoo again.

Author Bio:Graham Virgo is Professor of English Private Law; Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Education at the University of Cambridge