The rapid expansion of higher education in China has produced far more graduates than the labour market needs. Hence, graduate employment has become an increasingly challenging issue – not only from an economic but a social and political perspective. Without appropriate measures to handle graduate employment in mainland China, employment could become a serious problem with significant social and political consequences.

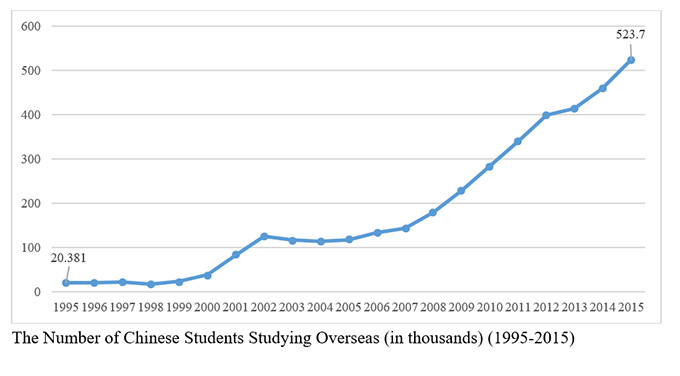

Against the context of the massification of higher education, there has been a growing number of families in mainland China sending their children to study abroad. In the last two decades the number of mainland students going abroad to study has increased more than twentyfold. Before the economic reform of the late 1970s, the majority of Chinese students relied heavily upon national scholarships to enable them to study abroad.

Nonetheless, there has been an unprecedented trend towards families and individuals as the main funding sources for study abroad. Because of the strong belief that overseas learning will enhance future job searches and career development, there has been a record number of mainland students embarking on overseas learning trips in the last two decades (see graph below).

Source: China Statistical Yearbook (1997-2016), National Bureau of Statistics.

Job opportunities for Chinese returnees

In our recent survey monitoring employment of Chinese returnee graduates, more than 80 per cent held master’s degrees obtained from overseas universities; 10 per cent had obtained undergraduate degrees; and 2 per cent had a doctoral qualification. The most popular subject was business, with nearly half of the students (47 per cent) choosing business programmes overseas.

Our study asked the respondents their reasons for returning to China to search for jobs. The majority of returnees cited emotional attachment and cultural affiliation (44 per cent) or the perceived good prospects of Chinese economic development and the relatively stable political environment (37 per cent) as their reason for returning home.

Importantly, 23 per cent of the respondents considered the job market overseas less favourable than in mainland China. During the job application process, securing a right “relationship”, or guanxi, is considered an important factor in China. Among the respondents, 17 per cent found their jobs through an “internal recommendation” from relatives and friends. However, for those without access to such relationships, the majority (about 60 per cent) relied on open channels or social media for job hunting. Meanwhile, only 12 per cent of respondents relied upon special platforms targeted at recruiting overseas returnees for jobs in China, and just 4 per cent found jobs through job hunters.

Many (47 per cent) of the returnees’ after-tax monthly income was CNY 5,000-10,000 (£580-£1,060). While 16 per cent secured CNY 10,000-15,000 and around 10 per cent secured more than CNY 15,000, more than a quarter earned less than CNY 5,000 per month. Another interesting finding revealed a mismatch between specialised knowledge and current job requirements.

While more than half of the interviewees agreed that they could match their academic studies (especially their majors) with their current job, about a quarter did not feel this was the case. About 15 per cent of the respondents did not consider their current jobs to match their skills and qualifications; only 7 per cent reported a match. Such findings clearly indicate that skill mismatch does happen in the Chinese labour market, which has also caused concern about whether higher education has prepared the right form of labour force for the Chinese economy.

Beyond hard knowledge, generic skills matter

To find out the most preferred graduate attributes that major employers are looking for, the same research interviewed 80 companies to solicit their views on this matter. Major aspects sought by employers are: problem solving abilities, teamwork, creativity and innovation, interpersonal skills and time management.

The present study also reveals that the majority of employers chose Chinese returnees because of their international outlook. Comparing the offers given to the Chinese returnees with those of graduates with domestic degrees, more than 80 per cent of employers offered better packages to the returnees. In addition, more than 20 per cent of these employers considered the promotion opportunities for the returnees to be better than their local counterparts, with 17.5 per cent saying that they would place the returnees in more core and managerial positions.

Comparing remuneration packages of different types of firms, the study reveals that half of state-owned enterprises would be eager to place the returnees in a core position, while other firms such as private enterprises or firms run by overseas returnees would be inclined to provide better remuneration to the returnees.

Putting the above findings together, it is obvious that Chinese returnees have relatively favourable employment opportunities although the competition among these returnees is becoming more intense. It also explains why these returnees are more positive when asked to evaluate their overseas learning experiences and career development.

Mind the gap: social and political implications

Most sociologically significant is that our analysis has suggested a gap is widening between the Chinese returnees and graduates from local universities. What makes the situation worrying is that most of the Chinese returnees come from families with better socio-economic status and have better educated parents.

Among the parents of the Chinese returnees under review, 45 per cent had undergraduate qualifications; 18 per cent obtained master’s degrees; and 5 per cent were PhD holders. The present study certainly sheds light on how social and cultural capital work for the Chinese returnees, acting as an effective enabler of career development and upward social mobility. However, we should not underestimate the social and political consequences when the gap between social groups in mainland China is widening.

If such a trend continues without appropriate public policy intervention, the intensifying education inequality will have a significant impact on social development and political stability in China.

Author Bio: Ka Ho Mok is Vice President of Lingnan University, Hong Kong and an international co-investigator at the Centre for Global Higher Education.