After four long days and nights, the European Council has reached a historic agreement on future spending. The next multiannual financial framework (MFF) and the Next Generation EU (NGEU) recovery instrument will commit the European Union to spending €1,824 billion (£1,660 billion) between 2021 and 2027. Compared with the 2014-20 MFF of €1,138 billion, this is a very impressive spending package, triggered by the onset of economic crisis.

But against this ambitious spending increase, the figures for Horizon Europe and for Erasmus+ are disappointing. Overall, Horizon Europe will only receive €80.9 billion, including €5 billion from the NGEU. The €75.9 billion reserved for it in the MFF represents only a marginal increase from the €75 billion allocated to Horizon 2020 – although the UK has attracted 14 per cent of Horizon 2020 funding, so, on a like-for-like basis, the money available to EU-27 members will increase from €64.5 billion. Still, there is no getting away from the fact that the overall increases in the headline budget are modest.

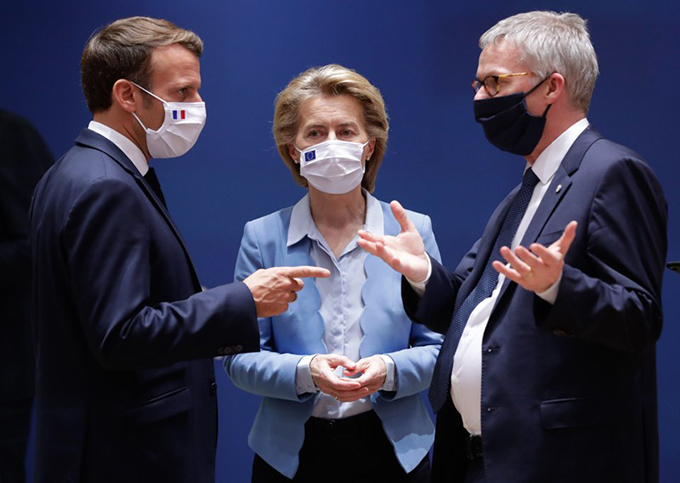

The fact that we are in the middle of a global pandemic – which only transnational research and innovation can address – was not enough to change national leaders’ short-term focus on their countries’ net contributions to the EU. Politicians clearly did not calculate that better science is a vote winner for them. Even where countries are clear net beneficiaries of Horizon, such as the Netherlands, political leaders preferred a budget cut, as a demonstration of their tough line, to strengthening their science base through investment in European research and innovation (R&I).

But this is not just about the perspectives of politicians. Nor is it simply a lament about what excites the media. The R&I community has evidently been unable to make the case to a wider public for the urgency of science.

It is now urgent for us to persuade national leaders to prioritise investment in science in their countries’ applications to the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) of the NGEU instrument. If that happened, the big R&I spending gap across Europe could be reduced, and science could still emerge as a big winner from this compromise.

Moreover, as the EU is set to relaunch the European Research Area (ERA) under the German presidency, there is an opportunity to align national research systems more closely and more visibly. One measure of the ERA’s success could be that in seven years’ time, the case for R&I as a distinctive European added value is inescapable, even at the level of European presidents and prime ministers.

Even as it is, there are silver linings in the current deal. Of the €13.5 billion that the council cut from the Horizon Europe budget proposed in May by the commission, the lion’s share (€8.5 billion) came from the NGEU instrument. The core Horizon Europe budget suffered a comparatively modest loss, from €80.9 billion to €75.9 billion. These cuts, which are likely to be applied proportionately to all instruments, are painful for the European Research Council and the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions, for instance. But the NGEU funds will be spent on close-to-market research and the European Innovation Council (EIC). Bigger cuts to the NGEU top-up of Horizon Europe should therefore increase the relative weight of fundamental research in the programme.

Moreover, it is truly remarkable that a new MFF and the NGEU instrument have been agreed at all. Only four months ago, few imagined that the stalemate around the commission’s 2018 MFF proposal could be broken. An emergency budget for 2021 did not seem at all unlikely. The fact that Horizon Europe now has a realistic chance of starting on time, on 1 January, is extremely good news for researchers, and it gives them some degree of certainty and assurance for the next seven years.

This agreement is also good for the UK’s prospects of associating with Horizon Europe for two reasons. First, the agreement will free up EU resources to focus on other priorities early in the German presidency, of which Brexit is one. Moreover, the council’s conclusions specifically mention that EU programmes should be open to third countries, and they also mention the need for a fair balance of contributions and benefits for them. Since the possible UK contributions to Horizon’s budget are among the key bones of contention in the current negotiations, this is clearly an important signal of goodwill on the EU’s part.

At yesterday’s debate of the European Parliament, which needs to give its legislative consent to the council’s compromise, research and innovation did emerge as a key area of concern. It may well be that the council, to avoid a parliamentary veto, responds by increasing the budget for Horizon Europe. If it did, it is hard to see how the “frugal five” – Denmark, The Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and Finland – could object given that they do so well out of Horizon.

Even if nothing changes, the outcome for science, while disappointing, could have been worse. At least we have a budget. And given the deep economic uncertainties ahead, its marginal gains might be a glass half full, rather than a glass half empty.

Author Bio: Jan Palmowski is secretary general of the Guild of European Research-intensive Universities and professor of modern history at the University of Warwick.