Apart from a few face-to-face return attempts which remain in the minority, we have been teaching at a distance for a year now, in the French university context. The majority of higher education teachers, who had to be trained quickly and imperfectly, find that the bodies are affected. Students and teachers spend long hours sitting behind their screens, stretching their legs during breaks to go to the kitchen for coffee.

Beyond the need for exercise which is increasingly felt in our numb bodies, it is all the elements of communication usually transmitted by the body that are upset.

Enter the frame

Like the actor, the teacher uses his body to bring his educational discourse to life. He produces hand gestures to facilitate understanding of what he is transmitting. The positive effects of pedagogical gestures have been demonstrated in particular for the learning of foreign languages and mathematics .

In addition, he also uses his facial expressions, his movements or his gaze to animate the class, evaluate the interventions of the students and create a climate of confidence.

However, when we go into videoconferencing, the use of the webcam imposes a certain number of constraints on the body. First of all, there is the immobilization on either side of the screen. The teacher must remain seated and ensure that he is well framed. His gestures must be seen by the students, forcing him to produce gestures towards the upper body, close to the face, which is not natural. Foreign language teachers, who often use pedagogical gestures to facilitate the understanding of the language by learners, play a lot on this framework .

In addition, teaching by videoconference brings about an unprecedented situation for the teacher: he sees himself in the process of teaching. His image constantly appears on the screen, and he looks at himself to check his framing or quite simply the image he gives of himself. This constant mirror makes us video conferencing Daffodils and is one of the factors in online interaction fatigue, called Zoom Fatigue (named after the most widely used video conferencing system today).

However, the teacher’s gaze is not always fixed on himself or on his supporting document. Indeed, he must also give the impression to the students that he is watching them. However, when you are online, to show the interlocutor that you are watching, you have to look at the webcam and not the screen. Only, the interlocutors, they are visible on the screen and not on the webcam. It is therefore necessary to make a choice of gaze orientation or alternate gazes towards the camera and gazes towards the screen to see the students to whom you are speaking.

Perpetual representation

See his students… They still have to be visible. In recent months, most of the higher education teachers who teach their courses online have observed the same thing: students are in hiding. Few of them turn on their cameras during lessons. There are many reasons. We can of course evoke those who connect to make an act of presence and go to do something else during the course but it seems to me that they are few.

A second reason is the fatigue of being online all day which forces you, if the camera is on, to be in some form of perpetual representation: looking attentive (and not yawning or doing anything else) , seated (and not slumped in your sofa which is tempting when you don’t move from your chair all day) and therefore probably scrutinized by the teacher and the other students.

Finally, if, as a teacher, we tend to imagine our students well installed at their desks, in a calm working environment, this is far from being a reality for all. Having regularly encouraged my students to turn on their webcams through fun activities for which they had to be on the screen, I was sometimes confused by what I saw around them: some were eating, others with children or roommates passing by to take a look at the screen.

However, the absence of the bodies and in particular of the faces of the students is not without consequence on the course of the course. On the one hand, it deprives the teacher of essential feedback signals (frowns, nods, smiles, etc.) which indicate that the students receive the pedagogical discourse and understand it (or not), which makes it possible to adjust the course thread.

On the other hand, for a teacher, being alone in his office, facing a screen, and talking to a set of small black rectangles bearing the students’ names is highly depressing. Teaching these invisible bodies is thus destabilizing for the teacher and has a negative effect on group dynamics. How, indeed, to construct the identity of a disembodied class-group?

Renew the link

All is not lost, however, and educational techniques exist. From a distance and in the current context, work on group dynamics is more important than ever because the students did not have the opportunity to get to know each other on the benches of the university this year. To want to show off, you have to feel confident and take the time to get to know each other.

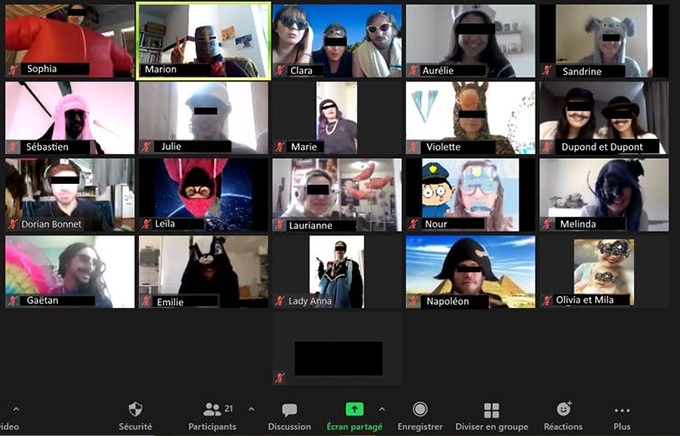

Icebreaker activities can be set up at the start of the semester and even at the start of the course as a warm-up. We can also offer virtual fund contests on an imposed theme where each student must turn on his camera and present himself in front of a photo in the background, which is easy to configure in Zoom. This activity went so well with my master’s students that one day they suggested that I go further and do a virtual carnival. We all appeared in disguise during the following course, which revitalized our discussions and gave a visible and assumed place to our bodies.

Finally, the work in sub-groups in virtual rooms is also very appreciable, it offers the students the opportunity to reflect on a document or an exercise in groups of 4 or 5 and we often find that it is easier to switch on his camera in this more intimate setting. These playful and dynamic activities, which will perhaps be judged as a waste of time in the university context, are on the contrary essential to rediscover the interactivity, verbal and non-verbal, so necessary for educational exchanges.

Author Bio: Marion Tellier is a University Professor in Language Teaching at Aix-Marseille University (AMU)