Earth’s last intact wilderness areas are being rapidly destroyed. More than 5 million square km of wilderness (around 10% of the total area) have been lost in the past two decades. If this continues, the consequences for both people and nature will be catastrophic.

Predominantly free of human activity, especially industrial-scale activities, large wilderness areas host a huge range of environmental values, including endangered species and ecosystems, and critical functions such as storing carbon and providing fresh water. Many indigenous people and local communities, who are often politically and economically marginalised, depend on wilderness areas and have deep cultural connections to them.

Yet despite being important and highly threatened, wilderness areas have been almost completely ignored in international environmental policy. Immediate proactive action is required to save them. The question is where such action could come from.

In a paper published in Conservation Biology, we argue that the United Nations’ World Heritage Convention should expand the amount of wilderness included in its list of Natural World Heritage Sites (NWHS).

Wilderness areas are underrepresented among the 203 sites currently on the list. The World Heritage Committee’s meeting in Poland this week offers a good opportunity to redress the balance.

Whither wilderness?

The World Heritage Convention was adopted in 1972 by UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) to conserve the world’s most valuable natural and cultural sites – places of exceptional importance to all of humanity and future generations. Each one is unique and irreplaceable. Currently, 193 countries (almost the entire world) are parties to the convention, which has inscribed 203 natural sites around the world.

World Heritage Status is granted to places with “Outstanding Universal Value”, which is defined based on three pillars. First, a site must meet one of the four criteria for listing as natural World Heritage (aesthetic value, geological value, biological processes, and biodiversity conservation). Second, a site must have “integrity” and “intactness” of its values (in other words, it must be in excellent condition). Finally, a site must be officially protected by the national or subnational government under whose jurisdiction it falls.

Wilderness areas can be associated with all four of the natural criteria, as well as the integrity and intactness requirements. What’s more, a wilderness by definition cannot be recreated once it is lost. The argument for protecting wilderness areas by adding them to the NWHS list is therefore compelling.

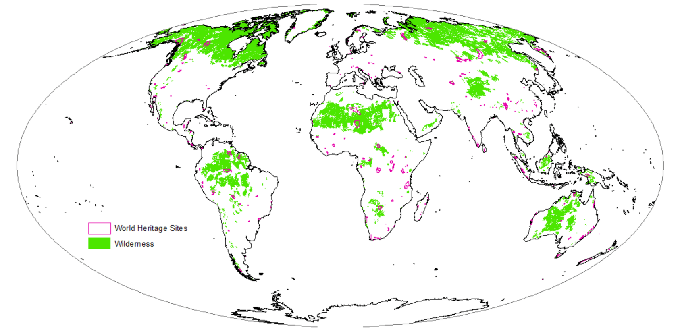

We created the most up-to-date maps of terrestrial wilderness using recent maps of human pressure and assessed the World Heritage Convention’s current coverage of wilderness areas. We found that some 777,000 square km (around 2% of the total) are already protected in 52 Natural World Heritage Sites.

Very little of the world’s wilderness (green) is within natural World Heritage Sites (pink). Author provided

For example, more than 90% of the World Heritage-listed Purnululu National Park in the Kimberley region of Western Australia can be defined as a wilderness area. Similarly, the Okavango Delta in Botswana features more than 18,000 square km of wilderness, containing many of the world’s most endangered large mammals.

Wilderness boosts heritage value

In these cases, wilderness areas are likely contributing to the Oustanding Universal Value of of these World Heritage Areas – which as explained above is a key consideration in how they are managed and protected.

One way to strengthen this protection further would be to redraw the boundaries of natural World Heritage Areas to include more wilderness. This would help to preserve the conditions that allow ecosystems and other heritage values to thrive.

Our study identified broad gaps in wilderness coverage by the World Heritage Convention. Some places are already protected by national governments and could therefore be added to UNESCO’s list, such as the Hukaung Valley Tiger Reserve in Myanmar, which contains 4,000 square km of wilderness, and the Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna Reserve in Bolivia, which has 9,000 square km.

The places we have identified, and others, could potentially be designated as new Natural World Heritage Sites if they meet the other strict criteria for Outstanding Universal Values and integrity.

The World Heritage Convention could better achieve its objectives and make a substantial contribution to the conservation of wilderness areas by doing these four things:

- formally acknowledge the Outstanding Universal Values of wilderness areas

- strengthen the current protection of wilderness within NWHS

- expand or reconfigure current NWHS to include more wilderness, and

- designate new NWHS in wilderness areas.

It’s up to national governments to submit sites for inscription as NWHS, and we urge them to consider wilderness when doing so. This will strengthen their applications, and provide wilderness areas with the extra protection they need.

The UNESCO World Heritage Committee’s meeting in Poland this week will consider two sites with significant wilderness areas for World Heritage status: Qinghai Hoh Xil Nature Reserve in China and Los Alerces National Park in Argentina. We urge the committee to approve these sites, and use this to spur further opportunities to raise the profile of wilderness conservation worldwide. It is an obvious win-win.

The clock is ticking fast for our last wilderness areas and the biodiversity they protect. Immediate action is needed.

Author Bios: James Allan is a PhD candidate, School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Management and James Watson is a Associate Professor at The University of Queensland