What do nuclear submarines, top secret military bases and private businesses have in common?

They are all vulnerable to a simple slice of cheddar.

This was the clear result of a “pen testing” exercise, otherwise known as penetration testing, at the annual Cyber Security Summer School in Tallinn, Estonia in July.

I attended, along with a contingent from Australia, to present research at the third annual Interdisciplinary Cyber Research workshop. We also got the chance to visit companies such as Skype and Funderbeam, as well as the NATO Collaborative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence.

The theme of this year’s school was social engineering – the art of manipulating people to divulge critical information online without realising it. We focused on why social engineering works, how to prevent such attacks and how to gather digital evidence after an incident.

The highlight of our visit was participation in a live fire capture the flag (CTF) cyber range exercise, where teams carried out social engineering attacks to pen test a real company.

Pen testing and real world phishing

Pen testing is an authorised simulated attack on the security of a physical or digital system. It aims to find vulnerabilities that criminals may exploit.

Such testing ranges from the digital, where the goal is accessing files and private data, to the physical, where researchers actually attempt to enter buildings or spaces within a company.

During the summer school, we heard from professional hackers and pen testers from around the world. Stories were told about how physical entry to secure areas can be obtained using nothing more than a piece of cheese shaped like an ID card and confidence.

We then put these lessons to practical use through several flags – goals that teams needed to achieve. Our challenge was to assess a contracted company to see how susceptible it was to social engineering attacks.

Physical testing was specifically off limits during our exercises. Ethical boundaries were also set with the company to ensure we were acting as cyber security specialists and not criminals.

OSINT: Open Source Intelligence

The first flag was to research the company.

Rather than researching as you would for a job interview, we went looking for potential vulnerabilities within publicly available information. This is known as open source intelligence (OSINT). Such as:

- who are the board of directors?

- who are their assistants?

- what events are happening at the company?

- are they likely to be on holiday at the moment?

- what employee contact information can we collect?

We were able to answer all of these questions with extraordinary clarity. Our team even found direct phone numbers and ways into the company from events reported in the media.

The phishing email

This information was then used to create two phishing emails directed at targets identified from our OSINT investigations. Phishing is when malicious online communications are used to obtain personal information.

The object of this flag was to get a link within our emails clicked on. For legal and ethical reasons, the content and appearance of the email can’t be disclosed.

Just like customers click on terms and conditions without reading, we exploited the fact that our targets would click on a link of interest without checking where the link was pointing.

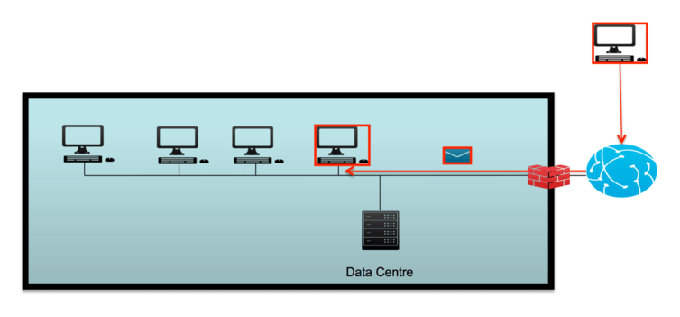

Initial infection of a system can be obtained by a simple email containing a link. Freddy Dezeure/C3S, Author provided

In a real phishing attack, once you click on the link, your computer system is compromised. In our case, we sent our targets to benign sites of our making.

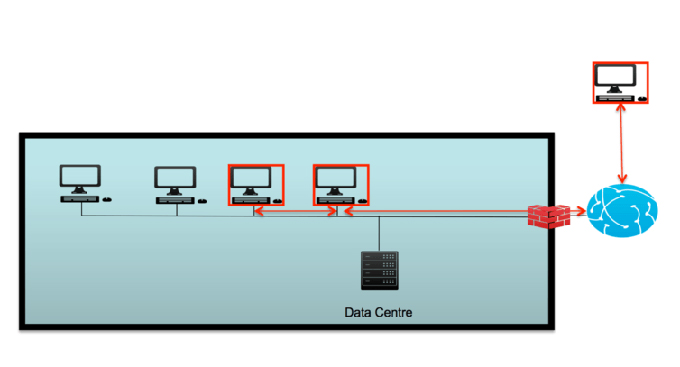

The majority of teams at the summer school achieved a successful phishing email attack. Some even managed to get their email forwarded throughout the company.

When employees forward emails within a company the trust factor of the email increases and the links contained within that email are more likely to be clicked. Freddy Dezeure/C3S, Author provided

Our results reinforce the findings of researchers about people’s inability to distinguish a compromised email from a trustworthy one. One study of 117 people found that around 42% of emails were incorrectly classified as either real or fake by the receiver.

Phishing in the future

Phishing is likely to get only more sophisticated.

With an increasing number of internet-connected devices lacking basic security standards, researchers suggest that phishing attackers will seek out methods of hijacking these devices. But how will companies respond?

Based on my experience in Tallinn, we will see companies become more transparent in how they deal with cyber attacks. After a massive cyber attack in 2007, for example, the Estonian government reacted in the right way.

Rather than providing spin to the public and covering up the government services slowly going offline, they admitted outright they were under attack from an unknown foreign agent.

Likewise, businesses will need to admit when they are under attack. This is the only way to reestablish trust between themselves and their customers, and to prevent the further spread of a phishing attack.

Until then, can I interest you in free anti-phishing software?

Author Bio: Richard Matthews is a PhD Candidate at the University of Adelaide