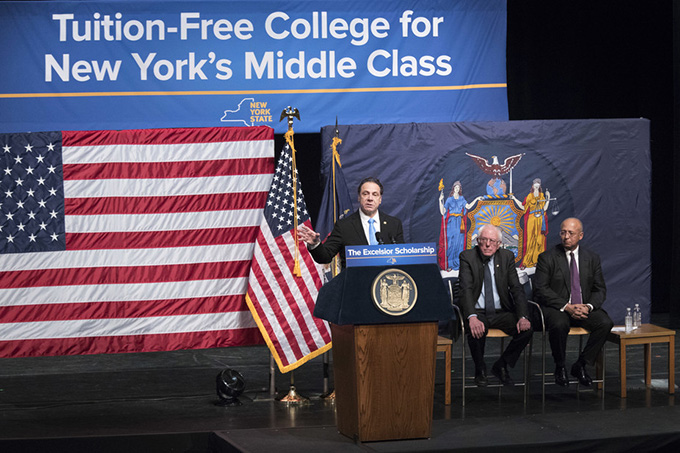

New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo recently pledged to make undergraduate education at the the City University of New York (CUNY) and the State University of New York (SUNY) system free for families making less than US$120,000 annually.

If this happens, it wouldn’t be the first time that undergraduate education has been free in New York. For most of its history, up until the 1970s when New York City was in dire financial straits and the state had to step in to bail out the City University of New York, CUNY was free to many of the city’s residents.

And this is not just the case in New York. College has been tuition-free in other states as well. In 2014, Tennessee governor Bill Haslam promised to provide free community college to all residents in his state. He has delivered on the promise, making Tennessee a model state in this area.

In a country where student debt and the rising cost of the college degree grab national headlines on a weekly basis, efforts to make college “free” can also get attention. In truth, however, a large part of tuition costs are already subsidized in the U.S. through a combination of grants, tax breaks and loans. What causes waves is the ever-increasing sticker price, rather than what students actually pay.

My interest, as a scholar of global education policy, is understanding how college costs in the U.S. compare to those of the rest of the world. The fact is that nowhere is college truly free. The critical difference is whether the bulk of the costs are born by the student or by the government.

So, what are some of the changes taking place globally as countries try to manage college costs?

Who pays?

Some countries follow a model similar to the U.S. by charging high tuition rates but then defraying the costs for certain students with grants, loans or tax incentives.

As to which country charges students the most, that depends on how one does the calculations.

Let’s look at the “2015 Education at a Glance” report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The report shows that public colleges in England charged the highest fees, when factoring in public aid, to domestic students (approximately ($9,000), followed by the U.S. ($8,200), Japan ($5,100), South Korea ($4,700) and Canada ($4,700).

But the numbers alone do not tell the full story.

A simple comparison between the total cost of tuition fees and the median self-reported income of the country reveals a very different picture: Hungary becomes the most expensive country, with 92 percent of median income going toward the cost of education, followed closely by Romania and Estonia. The U.S. ranks sixth on this listing. (This calculation does not factor in loans and grants.)

Low or no tuition models

Some countries take a very different approach, charging no or low tuition fees. According to the International Higher Education Finance, a project sponsored by the Rockefeller Institute of Government, more than 40 countries offer free or nearly free post-secondary education to domestic students. These include Argentina, Denmark, Greece, Kenya, Morocco, Egypt, Uruguay, Scotland and Turkey.

A variety of approaches are used to fund higher education in these countries, such as imposing high taxes or making use of their significant natural resources (e.g., oil and natural gas reserves) to provide the financial resources for extensive social investment.

In other places, such as Germany, an egalitarian philosophy and deeply held beliefs about the value of a public education preclude the government from shifting costs to the students. In Germany, for example, there was a short-lived effort from 2005-2014 to charge minimal tuition, which was rolled back after a major public outcry. Germans strongly believe that higher education is a public good to be totally subsidized the government.

The point being in these countries students pay very little for post-secondary education – a policy shift going on in the U.S.

The UK: A divided approach

There have been attempts in other countries to shift some of the cost of higher education to students.

Following the great recession in 2012, England, for example, tripled tuition in one year to approximately $11,000 (9000 pounds). The intent was to offset steep declines in government funding. Despite a significant outcry by students and other critics, these high tuition costs have stayed.

In fact, England recently surpassed the U.S. in terms of having the highest tuition fees of the 34 countries in the industrialized world. While the sticker price for many U.S. institutions is higher, financial aid helps bring down the total cost.

However, England’s “sister country” Scotland continues to provide more substantial subsidies for higher education, providing domestic students with free access to college while at the same time charging significant fees to students from elsewhere in the U.K.

What about international students?

The free tuition debate typically is domestically focused, but it can spill over into affecting international students. There are now more than one million international students in the US – comprising about 5.2 percent of the total number of college students.

The question now facing policymakers globally is whether to extend the concept of free college to international students or to let them be a source of additional revenues to offset costs of domestic students.

The no-tuition and low-cost tuition models have emerged as competitive advantages for attracting international students in many countries.

For example, a growing number of U.S. students are pursuing their degree outside of the U.S. in countries such as Germany and Scotland as they look for ways to escape the rising cost of college at home. Even though some U.S. students can receive subsidies to offset their education, those in the middle- and upper-income levels tend to receive minimal support and are also most likely to see studying abroad as a possibility.

New Zealand saw the number of international students quadruple from 2005 to 2014, soon after it made the decision to subsidize international doctoral students at the same level as domestic students.

In contrast, nations that have significantly increased their tuition costs for international students have found mixed results.

Denmark, for example, saw attendance from outside the EU drop by 20 percent in one year, after it introduced tuition fees for international students in 2006. Sweden too saw a massive drop in international students after it introduced fees in 2011-12 – the number of international students plummeted by 80 percent. (Some modest recovery has happened in recent years.)

Implications for U.S.policy

The issue in the U.S. is that it already has the largest share of the international student market – approximately 15 percent – and a steady stream of international students looking to study in the U.S.

In fact, state universities often seek to make up resource declines by increasing the number of full-fee paying international students. A recent report from the National Bureau of Economic Research found that a 10 percent reduction in state funding resulted in an 12 percent increase in the number of international undergraduate students at public research universities.

A number of questions therefore arise when considering the implications for the “free college” policies in the U.S.: Could free college policies reverse the trend of more U.S. students studying outside of the U.S. to escape high fees? Could improved state funding in support of making college more financially accessible to domestic students stop colleges from actively seeking international students? Or, could it push these students into the private sector which will likely have more room as students take advantage of free public education?

There are far too many variables still in play to answer any of these questions. But while the push for “free college” in the U.S. may be a sexy political move, we need to think through intended and unintended consequences.

Author Bio:Jason Lane is Chair and Professor of Educational Policy and Leadership & Co-Director of the Cross-Border Education Research Team, University at Albany at the State University of New York