Results from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2019 testing round were released last week. They showed Australia had improved in Year 8 maths and science, and Year 4 science, from the previous testing cycles.

The TIMSS is a standardised, international assessment administered to check how effective countries are in teaching maths and science. Another international standardised test is the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). PISA examines how well students in secondary schools across 36 OECD countries, and 43 other countries or economies, can apply reading, maths, science and other skills to real-life situations.

Standardised tests have been in place in a number of educational systems for nearly two centuries. They are rooted in reformers’ desire to regulate schooling and hold educators accountable, in the hopes of improving teaching and learning. But how did such exams gain momentum and why are they so controversial?

What are standardised tests?

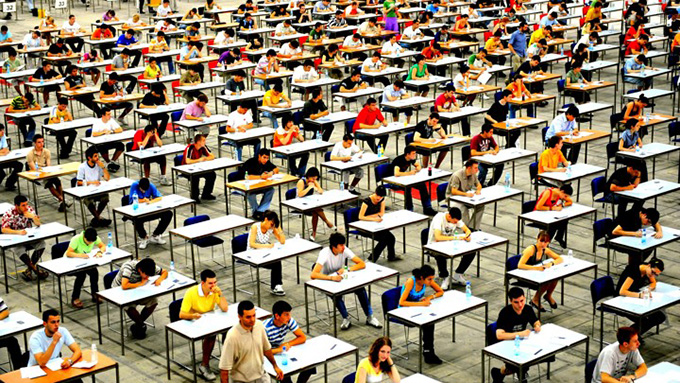

Standardised tests are exams administered and scored in a standard, or consistent, manner. They are scored using particular scales of standards in knowledge and skills.

Such tests can be given to large groups of students in the same area, state or nation, using the same grading system to enable a reliable comparison of student outcomes. The tests can be composed of various types of questions, including multiple-choice and essay queries.

In Australia, for instance, 740 schools and just over 14,200 students participated in PISA 2018. The results were compared to those of students in other countries, but also between students inside Australia.

Another well known exam is Australia’s national standardised test, the National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), intended for all Year 3, 5, 7 and 9 students across the country.

Similar testing programs to the NAPLAN can be found in other nations, including the UK, Israel, Germany, Mexico and Canada.

So how did it all begin and what makes countries take this approach?

A history of one-size-fits-all student testing

The 17th and 18th centuries saw English and American ministers preaching annual sermons to raise money to educate the poor. This appealed to the generosity of elites, while promoting policies that enforce tax support for charity schools.

The public expected to literally see the fruits of mass education during the industrial revolution; creating a reality in which fundraising and the display of students went hand-in-hand.

As William Reese describes in his prominent book Testing Wars in the Public Schools, “exhibitions” or “examinations” of learning became part and parcel of the US educational system. Such displays were used as a tool for citizens to judge teacher effectiveness and student accomplishment.

Once the days of exhibition were announced, educators’, students’ and even parents’ preparations began. It highlighted their eagerness to impress the public with the childrens’ knowledge.

Often reported by the press to lift community pride and morale, such exhibitions brought a milieu of people, including politicians and members of the school committee, who distributed prizes for meritorious achievement.

Students were focused on the task-at-hand, memorising topics and orally reciting ideas to impress the crowd. Impressions did not only rest on their public performance, but teachers’ ability to successfully discipline them “on stage”.

The rise of standardised testing in the US

By the early 1840s, US reformers Horace Mann and Samuel Gridley Howe, among other reformers, became frustrated by the “theatricality” of education and aggravated by the cruelty of corporal punishment and school exclusivity.

Mann and Howe had witnessed English reformers practising advanced statistics and debating the merits of competitive testing, which soon led to civil service reform and the appointment of inspectors to examine schools.

The two reformers grappled with fundamental questions such as “What makes one school better than others?” and “How can one identify changes in teacher practice and student learning over time?”.

They decided it was time to establish a more formal, consistent and critical testing program than a simple exhibition. They were in favour of written (rather than oral) exams in schools.

Materialising in various Boston grammar schools in 1845, the reformers surprised students with a one hour test attached to a blank answer sheet. A reality of competitive, written, standardised exams that offer quantifiable configurations of teaching and learning had emerged.

Holding sensitive school data in their hands helped the reformers to control issues of teaching, teacher promotion and leave, as well as acceptance and graduation in secondary schools (and later on higher education settings).

A new power battle became the centre of a long-lasting debate about the politics and the meaning of assessment.

What about Australia?

Standardised tests are not new to Australia. Research shows that since the 1800s, and although not consistently, some Australian students have taken part in some form of standardised tests to determine their knowledge, regardless of age.

Large numbers of students, for example, participated in half-yearly exams in the 1820s, administered by Principal Lawrence Halloran at his Sydney school. Similar to the US, external inspectors were also involved for some time in monitoring student achievement on various sets of tasks in schools.

But the standardised testing similar to what we’ve seen in the US was introduced to Australia in 2008 by way of the NAPLAN. This was accompanied by the MySchool website, which lists results for Australia’s students.

Then Federal Education Minister Julia Gillard introduced NAPLAN to give accountability and transparency to families and policymakers on student performance.

The message was very much familiar: let the crowd judge while we, the reformers, steer the schooling ship.

The tests drummed up similar controversy and criticism as in the US. It was mostly around them being a political and negative control mechanism, and their distorted critique (of what goes on in schools), waste (with regard to classroom time spent teaching to the test) and misclassification (reflection of the students’ socioeconomic circumstances rather than learning).

These came alongside confidence the tests can help diagnose learning gaps and keep parents, researchers and policymakers informed of students’ performance.

But NAPLAN’s cancellation during the 2020 COVID pandemic, as well the hiatus of standardised tests in other countries like the US, has made interested parties question whether it may be the beginning of the end of the obsession with the testing method.

Where to now?

Some successful education nations like Finland — which rank highly in international standardised tests like PISA — avoid external, national standardised tests.

Finland has been a poster child for school improvement since finding its way to the top of the international rankings after emerging from the Soviet Union’s shadow. The country has magnificently shifted from a centralised education system, that celebrating external testing, to a more localised one in which highly trained educators provide more narrative feedback to students.

As the Finnish policy analyst Pasi Sahlberg explains, Finland has made a conscious decision to avoid investing in standardisation of curriculum enforced by frequent external tests.

Instead, it focused on teacher education and providing time for teacher collaboration on issues of instruction. Student-free daily meals, health care, transportation, learning materials and counselling are also part of the package.

With the ongoing conversation about quality, possible assessment alternatives and new ways of schooling, only time will tell whether standardised testing programs continue shaping Australian and international education practices.

Author Bio: Ilana Finefter-Rosenbluh is a Lecturer, Faculty of Education at Monash University