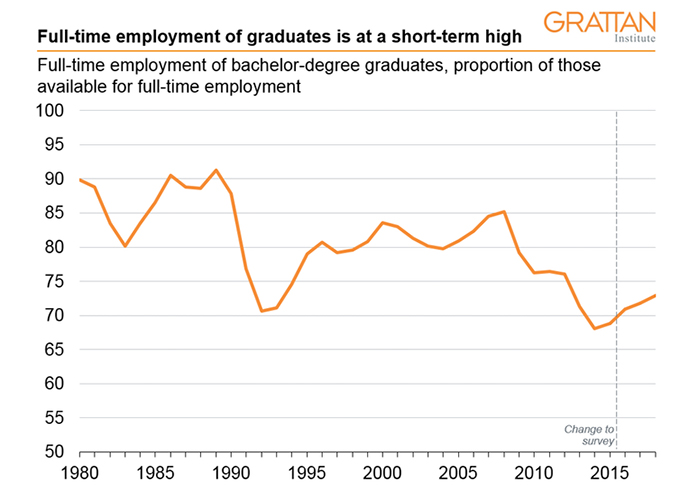

Four years on from the worst new graduate employment outcomes ever, the 2018 statistics released today show cause for optimism. Although full-time employment rates remain well down on a decade ago, they are improving.

Graduates in health-related courses fare the best

In early 2018, about four months after completing an undergraduate course, 73% of new graduates who were looking for full-time employment had found it. This continues a positive trend since the low point of 68% in 2014. But apart from the early 1990s recession, it’s still a poor result by historical standards.

Full-time undergraduate employment rates, approximately four months after completion. Department of Education and Training, Graduate Outcomes Survey and Graduate Careers Australia, Graduate Destination Survey

These overall results hide substantial differences between graduates of different degrees. As usual, health-related occupations have the best employment rate, with medicine, pharmacy and physiotherapy recording more than 90% employment.

Also as usual, graduates in the visual and performing arts have the worst outcomes, with just over half in full-time employment. Biological sciences graduates did better in 2018 than 2017, but with 58% in full-time employment they’re still in a tough labour market.

A follow-up survey three years after graduation suggests employment rates improve significantly over time, although the strong fields at the four-month point usually retain their top position.

Job quality is stable

Compared to 2017, job quality for new graduates in 2018 is stable. In both 2017 and 2018, 72% of graduates working full-time were in professional or managerial occupations. On a more subjective measure, in 2018 27% of graduates with full-time jobs felt they were not fully using their skills, slightly up on 2017.

Unfortunately, graduates from courses with poor overall full-time employment rates also have relatively low rates of professional and managerial employment and relatively high rates of reporting their job does not fully use their skills.

Starting salaries are up slightly, but the gender gap has increased

Median starting salaries also differ significantly between fields in 2018, ranging from a high of A$83,700 for dentistry to a low of A$47,000 for pharmacy. This reflects their system for professional registration.

The overall median starting salary in 2018 was A$61,000, up from A$60,000 in 2017. This roughly reflects salary increases across the overall labour market.

In 2017, the graduate gender pay gap had narrowed to men earning 2% more than women. But in 2018 it widened again to 5%, or A$3,000 a year. Some of this is due to men choosing courses that lead to higher-paying jobs. But even in highly-feminised fields such as nursing and teaching men report slightly higher median salaries.

Prestige universities do not provide better outcomes

At first glance, the most surprising results in this survey are those reporting outcomes by university. Students from some of the most prestigious universities report poor employment and salary outcomes, while students from some regional universities do very well.

These counter-intuitive results highlight the importance of looking carefully at other characteristics of graduates. Regional universities enrol more mature-age students than big-city sandstone universities. Older people often already have work histories and current jobs, which is why they earn more when they graduate.

Sandstone universities are also more likely to have large arts and science faculties, and graduates in those fields can drag down median salaries. Even so, previous studies have found employers typically don’t initially pay a wage premium to graduates from sandstone universities. They want to see performance before they pay more, rather than trust university prestige.

Employer satisfaction

The complicated issue of graduate quality is examined in another report released today, the employer satisfaction survey. This survey has a bias, as it relies on graduates nominating their supervisor to participate.

Graduates who think they’re doing badly are unlikely to nominate their supervisor, so the report’s 85% overall employer satisfaction is probably above the true number. But the survey is still useful for comparisons.

As with some of the other employment outcomes, employer satisfaction by university does not follow any prestige-based pattern. Only one sandstone university, the University of Queensland, makes it to the top ten universities by employer satisfaction. Bond University graduates have the most satisfied employers, followed by Western Sydney University and James Cook University graduates.

While employers were generally happy with their graduate hires, 40% said the qualification could have better developed graduates “technical and professional skills”. That seems high. On the other hand, few employers (5%) suggested the qualification could improve “teamwork and interpersonal skills”.

Job growth is critical to employment outcomes

The government wants universities to do more on graduate employment. Graduate job outcomes are likely to be part of new university performance funding scheme.

But as the Minister for Education, Dan Tehan, says in his media release on these reports, job creation is crucial. Especially as total graduate numbers continue to increase, job growth is the vital link between employability, which universities can help with, and actual employment for their graduates.

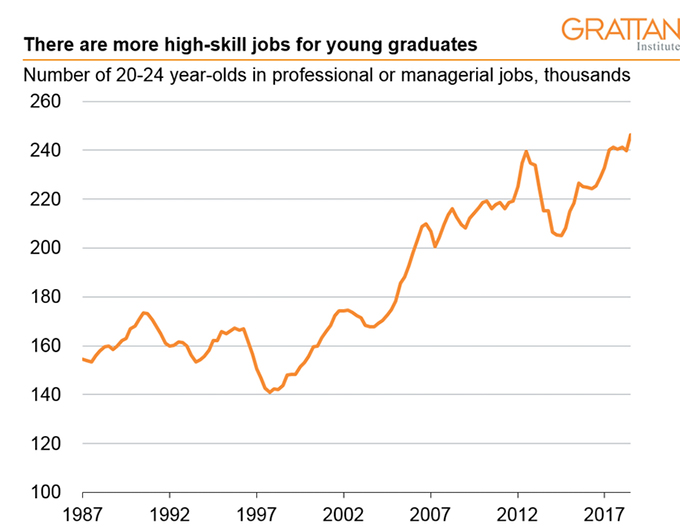

In 2014, an increasing number of graduates collided with a declining number of professional and managerial jobs for people aged between 20 and 24 years. This is what caused the worst-ever graduate employment outcome.

Professional and managerial jobs, people aged 20 to 24 years. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Detailed labour force

But since 2014, with a couple of hesitations, the jobs trend has been positive. Job numbers were still going up in late 2018, which is a good sign for recent graduates looking for work.

The labour market will always fluctuate, but at least in the short term both the outcomes survey released today and the latest ABS figures suggest employment opportunities for graduates are increasing.

Author Bio: Andrew Norton is Higher Education Program Director at the Grattan Institute