Like many academics, I get to my office every morning and battle the problem of Too Much To Read.

To tell the truth, most days I give up the fight. Under pressure to publish or perish, academics are producing mountains of text every year, even in a tiny sub-specialty like research education. I don’t have enough time to read all the new papers in my discipline just to ‘stay informed’. I only read academic papers if I absolutely have to; usually when writing a literature review. I’m still an avid reader in my down time, but my textural diet consists mostly of popular, non fiction books that make an effort to engage me as a reader (and romance novels, which actually have stories).

I feel slightly ashamed to admit that I largely ignore the literature my colleagues produce, but in my defence, typical academic writing is, well … dull.

I don’t blame my academic colleagues for the volume of dull writing they produce – I have certainly contributed my fair share to the pile. Luckily for me, I have to teach workshops about writing , which has forced me to make an effort to continuously improve my craft. The best way to learn is to teach, which is why I was pleased to team up with Katherine Firth and Shaun Lehmann on a couple of books about writing. Our first one How to fix your academic writing trouble has been a strong seller and we have a new one out next month called Level up your essays. (Level up is aimed at undergraduates, so won’t necessarily be of interest to you, although you may like to point your students at it).

Working on these books with clever co-authors has been a wonderful learning journey, but the work of improving your own writing is never done. One way to make your writing more engaging is to understand how readers’ brains process text.

Our brain has all kinds of ‘hacks’ to speed the process of reading. Think about it for a moment: if we did a mental ‘look up’ of the meaning of each word as we see it on the page, it would take a month to read a couple of pages. When we read, our brains look for recognisable ‘slabs’ of text; certain arrangements of words we’ve come to expect to see after decades of reading English. Researchers call these slabs ‘schemas’.

A schema is a plan or model; in text, schemas are recurring patterns of words. For instance, adjectives in English need to appear in this order: opinion – size – age – shape – colour – origin – material – purpose – Noun. Muck this order up even slightly and your reader is instantly confused. Here’s an example from Mark Forsythe’s Elements of Eloquence: A lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife makes some sense, but A lovely little old rectangular French silver green whittling knife does not.

Why? No one really knows! Brains hey? Weird.

The most important English language schema is subject-verb-object. A simple example of subject-verb-object formation is:

Darwin studied finches.

ICYMI: Darwin (subject – the doer) studied (verb) finches (object that was acted on).

The subject-verb-object form works because it feeds the brain information about action in the world. In the sentence Darwin studied finches, Darwin is doing the studying and the finches are the ones being studied. If you jumble it slightly and wrote Studied Darwin finches, your brain is not sure what action is happening and must slow down to process it, word by word. To our reading brain, this is like driving along at 100kms an hour down the word highway and suddenly having to jam on the breaks to avoid a hole in the road.

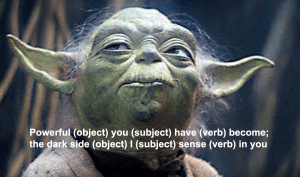

Luckily, brains are flexible. They will usually distill the meaning from a sentence, even if you muck up the subject-verb-object order. In fact, sentences that deliberately muck it up can even be fun, which is why when Yoda says Powerful you have become; the dark side I sense in you, he comes across as endearing, rather than incomprehensible:

A colleague of my husband, Adam Ratcliff, calls getting the subject-verb-object consistently mixed up ‘Yodanating’. Of course, the no-fun Darth Vadar wouldn’t be caught dead Yodanating:

Your brain is hooked on subject-verb-object and will look for it, even when it’s only suggested, which (side note) is why certain road signs in Canberra are so irritating:

If a sentence makes you slow down to try and understand what is happening, you have probably stuffed up the subject-verb-object order. I pride myself on being a good writer, but my published papers are full of sentences that break this basic subject-verb-object rule. Consider this clunker, from a paper I published with colleagues a couple of years ago:

The growing awareness of a range of possible career destinations for Ph.D. graduates has led to widespread questioning of the ‘traditional’ model of the Ph.D.

Can you see the subject-verb-object schema anywhere? Here, I’ll colour code it for you so it’s easier to see. I’ll use orange for subjects (usually people, but not always), green for verbs (‘doing words’) and blue for objects (usually things or concepts, but sometimes people):

The growing awareness of a range of possible career destinations for Ph.D graduates has led to widespread questioning of the ‘traditional’ Ph.D curriculum.

The sentence is so confusing I am not sure I got the colour coding right. ‘Ph.D Graduates’ could have been orange I suppose? But the Ph.D graduates are not doing anything – if there’s action in this sentence it’s the questioning. But who is doing the ‘questioning’? We are left to guess.

The fix for clunky sentences like this is easy: just make it clear who is doing what to whom. Let’s populate the sentence with some proper ‘doers’ of actions and see what happens:

Research suggests PhD graduates have a broad range of possible career destinations, which has led scholars to question the utility of the ‘traditional’ PhD curriculum.

Much better. The reworked sentence even has two subject-verb-object clusters: our brain feels like it’s at an action movie!

Sentences with complete schemas are more compelling because our brains don’t have to struggle to distill meaning. Your brain likes to see the subject-verb-object cluster close to the start of a sentence so that it can satisfy itself about what action is taking place before it gets to the clarifying details.

In our re-worked sentence above, there’s a subject-verb-object cluster right at the start, with a bit of explanation and clarification right after it. Here, I’ll highlight the extra stuff in pink:

Research suggests PhD graduates have a broad range of possible career destinations, which has led scholars to question the utility of the ‘traditional’ PhD curriculum.

My friend Paul Magee recently pointed out that linguists call this kind of structure a ‘right branching sentence’. During a recent nerdy lunch, where we planned a podcast series about brains and writing (stay tuned!), he pointed out that brains prefer right branching sentences because they occur frequently in speech. Speech-like sentences are pleasing to the brain for a very special reason. When we read, our brain uses the sound processing circuits in the brain to generate an ‘inner narrator’. This is why we talk about a ‘writer’s voice’: from our brain’s point of view, when we read we are listening, not looking.

The opposite of a right branching sentence is a left branching one, where the clarification or modification appears before the action in the subject-verb-object cluster. Peter Elbow, in his book ‘Venacular Eloquence’ points out that left branching sentences are hard on the brain because they force it to do more work. Take this sentence, again from one of my papers (oh the shame!), which has a whole lot of explanation before we get to the subject-verb object cluster. I’ve highlighed the left branching explanation bits in pink:

When consulting with employers about the range of skills a PhD graduate should have on completion in order to be employable, academic managers typically take a round table approach.

This left branching sentence forces the brain to ‘hold’ a lot of information about what the academic managers are doing before applying it to the action. It’s the kind of sentence that forces the reader to go back to the start after they have finished in order to really understand what is going on. Rather than making your reader jam on the breaks, you are forcing them to go all the way around the roundabout again before exiting.

I see this kind of left branching sentence construction ALL THE TIME in student writing, and in academic writing more generally. I think researchers are particularly prone to excessive left branching because our brain is so loaded with detail when we write. Scholarly writing is also defensive: we feel the need to qualify everything we say before we say it, just to make sure the reader knows we have done our due diligence.

It’s hard to avoid a left branching sentence, but you will get away with it if you make the left branch quite short. This enables readers’ brains to more easily ‘hold’ the information you want to apply to the action, like so:

When consulting with employers, academic managers typically take a round table approach.

I hope this little detour into brain science has given you some tools to make more brain-ready sentences!

Comments are still off, but you can talk to me on Twitter by tagging me with @thesiswhisperer. I might be blogging less, but I am using the time to pursue my podcast hobby: the first On The Reg podcast for 2021 is now up for your listening pleasure!

In solidarity and grammar nerdery,