Writing about literatures doesn’t mean writing a summary of what you have read. You dont want a paragraph by paragraph laundry list of the texts you’ve been reading organised into a rough kind of order. Of course you write summaries as a means of making sense of your readings, but it’s not where you stop.

In writing about what other people have written you are:

- evaluating and interpreting, pulling out major points and

- connecting these interpretations to your topic.

So what you are writing then is not a report, but an argument. You are saying how you work sits in the field and how the field informs your work. This is arguing a case. Your case. Your argument is based in what you think the literatures mean and how you have understood them. You must then not only establish where your research fits in relation to the topic, what you are building on but also what you might want to speak back to, or expand further.

There are ways to make this writing task easier for yourself.

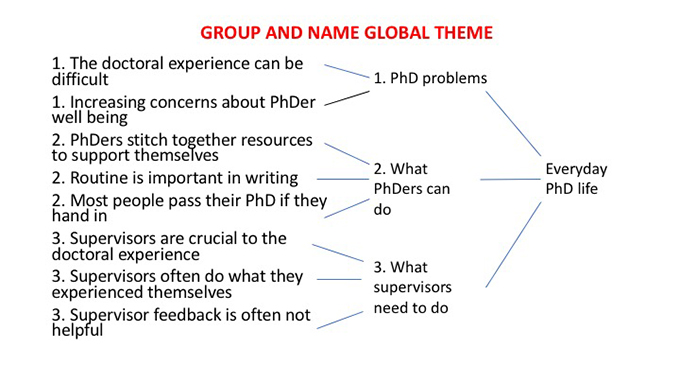

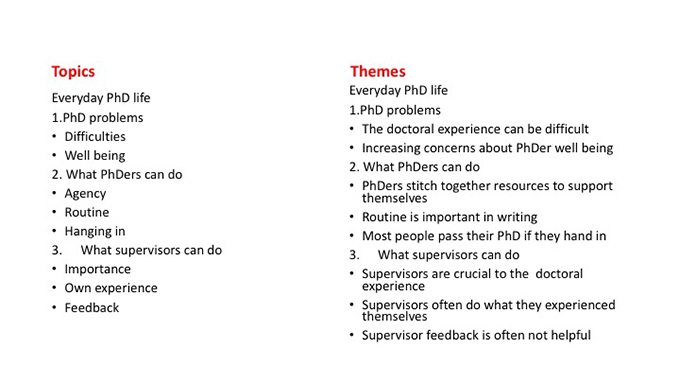

In the first part of this post I talked about developing three levels of themes from the data, and I showed how the three levels allowed you to structure a single piece of writing, a chapter, or establish where a global theme might fit as a section of a chapter. Here’s a reminder.

So how to you get from that to the argument? You have the structure but is that enough?

One helpful strategy for making the argument is to go back to the basic themes. You”ll notice that I’ve written the themes as points, not as topics. Each theme expresses the sum of an interpretation of a body of texts. The themes, as Ive written them, are more like the reminder notes you might have if you are speaking in a debate. Each bullet signals the line you are going to take and the thing you want the reader/audience to remember.

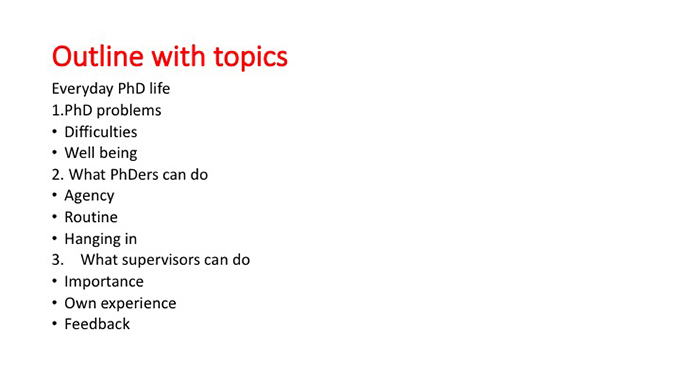

Now, I often see people working with outlines when they write chapters. The outline that they use usually has headings and subheadings. The outline looks a lot like a table of contents. The outline lists the topics that are to be written about. It might look like this.

Now the risk of this topic-based approach is that it doesn’t actually tell you what you have to say. What is it that you need to say about wellbeing, or supervisor experience? What bit of agency are you going to write about?

Well, it’s not that you don’t know this. You have this all in your summaries of readings so you can go back and orient yourself. However, the temptation of a topic approach is that you simply to write summaries and/or you find it tricky to pull out the key thread that is most germane to your work.

Outlines also support a tendency to write in little bites. First this topic, then that one. This kind of choppy writing is a characteristic of a lot of literatures writing and it’s one that makes it unnecessarily hard for readers – the struggle to put the bits together to follow the line of argument being made.

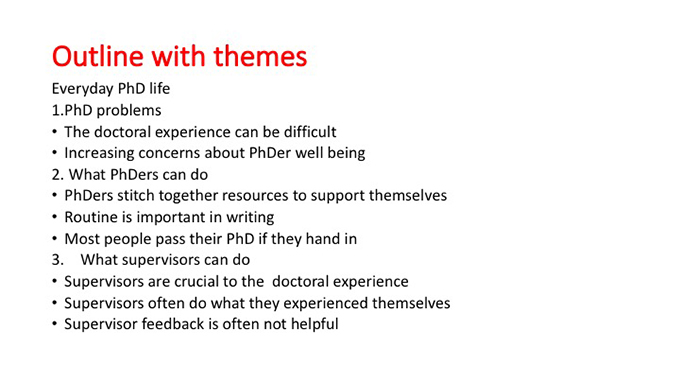

Working with a topic outline is not the same as working with themes.

Working with themes rather than topics allows you to do two important things –

- you have in front of you as you write, the point you want to make, the point that you are building on, the issue that is most important to your work, that you take up in your research design and/or analysis. So you have that in mind as you start to write. You know that this is the idea that holds these literature together and that you must both show and discuss. As a bonus, having the points of each basic theme clear also helps you to be more concise.

- you can see what is missing. If you look at the third element of this chunk on the doctoral experience you can see that these three things don’t appear to follow particularly logically from one another. It might be that there are some bits missing here, or I need to revisit my themes. Either way, focussing on the steps taken by the basic themes will allow me to see and get flow – a logical progression from one basic theme to another.

Compare the two -points and themes – and see the difference. Imagine using both of them as the guide to your writing. I hope you can see the difference that a point might make.

Working with themes and not topics is a writing strategy. It isnt the final thing. You don’t necessarily want the reader to see all of your scaffolding in the final text. So, when you do write the final table of contents, you usually convert the themes to topics. This is something that you do on a second or third draft once you’ve got the sequence and flow of argument sorted out.

For a first draft, working with themes can really help. Give it a go yourself and see the difference it can make.