The new learning economy is creating opportunities for universities to move on from the current focus on cutting costs, downsizing and job losses. Many universities appear stuck in a downward spiral, but now may be the time to offset this with new initiatives. Growth in the need for ongoing learning creates these opportunities.

Current education providers, as well as new entrants, have the chance to replicate the business models and innovative practices of Spotify, YouTube, Uber, Airbnb and other disruptors of other sectors. For example, we can envisage a platform provider brokering crowd-sourced production of education content. The resourcing of expertise from the higher education sector would provide access to new, scaleable and more widely available forms of academic content.

Significant disruption is imminent. We believe those with ambition will thrive in the emerging new learning economy. They will not only disrupt, but also generate new forms of demand and supply for education.

Old assumptions overturned

The education market has been stable for generations. This stability has relied on three assumptions.

First, knowledge gained through upfront education equips people to master the immediate and ongoing needs of work. As a basis of lifelong competence, the knowledge gained by novice professionals is expected to be sufficient for career entry and beyond.

Second, as we gain experience in our career, we only occasionally require new learning. Experience builds incrementally and continuously on upfront knowledge over time, leading to ever-increasing competence.

Third, there is no need for learning consciousness. In other words, the individual does not need to know how much they know, what else to learn, or how to unlearn.

These assumptions have driven government policy, student demand, employer practices and university business models. With changes to the future of work and digital disruption, these assumptions can now be seen as creating three systemic learning disorders:

- the rate of innovation and knowledge development has accelerated, so our knowledge is out of date sooner

- experience gained through repetitive work and professional practice is of less value in a world of changing practices and new requirements

- our competence is something about which we have less consciousness or literacy – we increasingly don’t know what we don’t know, and not knowing how to learn and unlearn matters even more.

The 3 learning disorders explained

We illustrate these disorders in the three charts below. These plot the way knowledge, experience and competence develop over lifetimes, and the impacts of the emerging learning disorders.

The first chart uses a simplistic model of learning development consistent with the seminal work on self-efficacy in education of Caprara et al. The underlying idea is that competence is a combination of knowledge gained from learning and experience gained from working.

The traditional model of learning: knowledge and experience combine to form competence. Author provided

However, competence is not sufficient. Similar to our understanding of physical well-being (for example, is my blood pressure OK?) or financial well-being (will I have enough super?), we need consciousness about our competence. We suggest this is the basis of educational well-being. The pursuit of this goal gives rise to the new learning economy.

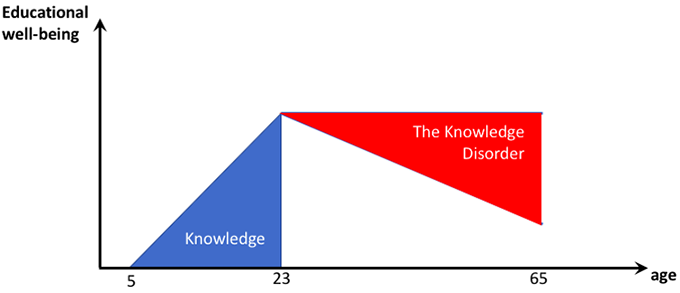

The first disorder, the knowledge disorder, shown in the chart below, captures the fact that the knowledge gained from formalised learning now decays more quickly. This happens due to faster rates of innovation and knowledge development within the periods that learning had been designed to serve.

The knowledge disorder: knowledge is decaying more quickly. Author provided

The rate at which knowledge grows and develops has overtaken our intention to create novice professionals with knowledge lasting a lifetime. One-off degrees that testify to a certain qualification at a certain point in time are no longer sufficient. The world requires educational well-being as much as it requires a healthy and prosperous population.

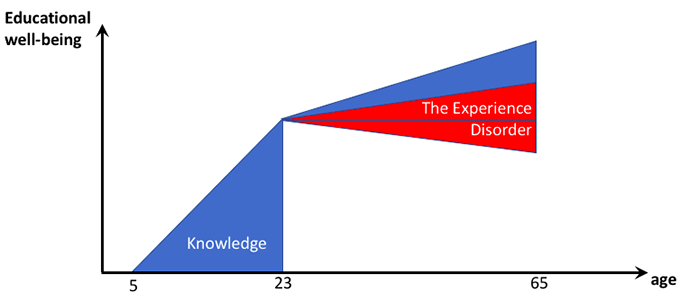

The third chart shows how the value of experiences we gain in the workplace has changed. No longer does cumulative experience lead to increasing competence. Experiences of old ways of doing things are becoming hindrances to ongoing competence in disrupted environments.

The experience disorder: experience can become unhelpful. Author provided

As a result, experience might matter less. Even worse, it could become counter-productive when unlearning established practices becomes increasingly difficult. In some situations, current knowledge has become more important than past knowledge with added experience.

We can see the impacts of this experience disorder in recent years. Large organisations have let “experienced” staff go, then hired new graduates with contemporary knowledge. NAB was criticised for doing this.

How should education respond to these changes?

We predict we will see on-demand, tailored and customised learning on new platforms. These may be ubiquitous and scaleable programs of what are being called micro-credentials. Google’s “career certificates” are one recent example.

We foresee a need to support continuously improving workplace experience through partnerships between educational well-being providers, maybe universities, and providers and receivers of workplace experiences, employers and employees. We see opportunities for new, platform-based, lifelong experience-management services.

The consciousness disorder arises from us being unaware of how change undermines competence. As US secretary of state, Donald Rumsfeld famously coined the term “unknown unknowns” in highlighting the danger in dealing with complex, fast-changing situations. In such a world, competence becomes more fragile, but we are not aware of it, which makes us vulnerable to disruption.

We can foresee new services to help identify unconscious incompetence. Maybe automated online “health checks” of educational well-being will be made available to alumni. This service could be aligned with personalised access to new knowledge to address gaps.

We believe that responding to these three disorders, in these sorts of ways, provides a blueprint for a new learning economy. This learning economy is global and will scale up to satisfy the demands of citizens who are no longer served by our current model of education.

This evolution of education will not only present new directions for established education providers, but also attract new competitors. They might range from ed-tech start-ups with niche services, to others that see the global learning economy as a high-growth opportunity. Google is unlikely to be the last new challenger to the traditional university model.

Author Bios: Martin Betts is Emeritus Professor at Griffith University and Michael Rosemann is Director, Centre for Future Enterprise, and Professor for Innovation Systems, Business School at Queensland University of Technology