The disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has been so profound, particularly for women, that it threatens to upend the progress on gender equality in recent years. During the lockdown, women were doing more of the unpaid labour – care and housework. They were also more exposed to the risks of coronavirus either as essential workers or working in industries, such as retail, hospitality and accommodation services, that were forced to close.

The disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has been so profound, particularly for women, that it threatens to upend the progress on gender equality in recent years. During the lockdown, women were doing more of the unpaid labour – care and housework. They were also more exposed to the risks of coronavirus either as essential workers or working in industries, such as retail, hospitality and accommodation services, that were forced to close.

There is evidence also of significant impacts on men’s labour force participation. In some cases men’s job losses early in the pandemic have not been recovered.

The impacts of COVID-19 on women and men extend beyond work and home to education, particularly tertiary education enrolments.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ latest data, 112,000 fewer students were enrolled in tertiary education in May 2020 – at the height of the first wave – compared to a year earlier. This is the largest drop in enrolments in over 15 years.

Like other aspects of COVID-19, the impact was gendered with a far greater decline among women. There were 86,000 fewer women enrolled to study in May 2020 than in May 2019, compared with just over 21,000 fewer men.

Big fall was for women over 25

What do these data tell us about COVID-19, education, work and potentially the future?

These data tell us COVID-19 has not only severely disrupted the lives of women in the workplace and the home, but also in education.

The biggest decline in tertiary enrolments was among women over the age of 25: 60,000 fewer women over 25 were enrolled in university in May 2020 than in 2019.

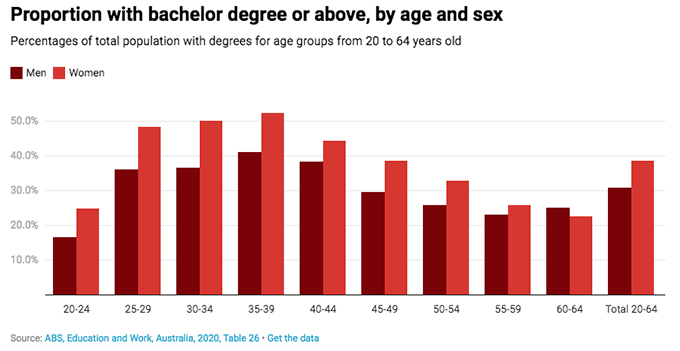

This steep decline in enrolments is particularly surprising given Australia’s success in educating women and potentially puts the nation’s reputation at risk. Australia is ranked equal first in the world in terms of educational attainment for women, according the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Gender Gap Index. The country has been atop the list for well over a decade.

Juggling caring roles with study

These data remind us caring responsibilities not only affect careers or work-life balance, but also education. The sharp decline in female enrolments over the age of 25 suggests it was likely because of caring responsibilities.

Many of these women with caring responsibilities, for either young children or older family members, were likely forced to make a choice between caring and studying. And for those combining work and study on top of family commitments, many elected not to continue studying.

For many mature-aged students (those over 21), undertaking study is challenge, especially for those combining study with work and/or care. Previous research has shown a number of gendered expectations are put upon mature-aged students and their time.

For many of these mature-age women who are combining work and study, they increasingly do it flexibly or online and schedule it around other commitments. Others give up their leisure time for learning.

COVID-19 made that near-impossible. The loss of both family and formal childcare increased the burden of unpaid work for women at home. It was extended far into the workday and into the evenings where mature-aged women might ordinarily find time to study.

Enrolments rose for men over 25

The data also highlight the gendered complexities of COVID-19 on education. Women’s enrolments were disproportionately affected, whereas the data showed significant increases in men over the age of 25 enrolling in university in May 2020 compared with 2019. Male enrolments in this age group increased by about 26,000.

This increase suggests men were either “forced” into tertiary education because of a lack of opportunities, or it was a deliberate strategy on their part to upskill so they could be more competitive for jobs once the economy recovers. In this way, older age groups of men have shown themselves to be similar to young people who tend to go into education during times of recession. This is perhaps in contrast to previous recessionary periods where the participation rate of older men declined considerably.

All of this has implications for the future, particularly for women. These data are worrisome because, even though the returns from education for women are poor, many women obtain a number of qualifications just to get on an even keel with men in the labour market.

These latest trends might make it harder for women in the long run. However, it is worth noting these data capture enrolments at a point in time – during the first wave of the pandemic. Things might have changed significantly since then.

Author Bio: Brendan Churchill is a Research Fellow in Sociology at the University of Melbourne