It’s that time of year again when hundreds of thousands of Australian students start university for the first time. Commencing students account for about 40% of the more than 1.6 million Australians enrolled in university (as at 2019, the most recent available data). It’s an important step for many in pursuing their educational and occupational dreams.

Those who are first in their families to pursue higher education can find this momentous step both exciting and daunting. “First in family” refers to students whose parents do not have a university degree. They are complete “newcomers” to higher education.

University is uncharted territory for these students, their families and even their communities. Our research shows “first in family” students often face complex and multiple forms of disadvantage that shape their transition to university. Despite this cohort of students now accounting for about half of university enrolments nationwide, government and university policies often overlook the particular challenges they face.

Only about one in four Australian adults hold a bachelor-level or higher qualification. But if a young person has a university-educated parent that almost doubles their odds of attending university.

An overlooked equity category

Australian universities are now often described as being open to the masses. However, the enduring relationship between parental education and university enrolment harks back to the days of an elite higher education sector.

For the past three decades, the Australian government has invested heavily in programs to widen participation in higher education. The aim has been to create a student body that more closely reflects the broader population.

The government has focused on a number of groups that are underrepresented in higher education, usually because of social, economic and/or educational disadvantage. These “equity target groups” are:

- Indigenous Australians

- people from low socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds

- people from regional and remote areas

- people with disabilities

- people from non-English-speaking backgrounds (NESB)

- women in non-traditional areas of study.

Improving access to university for these groups is vital for a fair and just society. However, our research shows first-in-family students are overlooked in this equity agenda.

A clear gap in aspirations

Our study focused on students in primary and secondary school. We drew on survey data from 6,492 students (across Years 3 to 12) enrolled in 64 government schools in New South Wales. The survey was part of a larger four-year project examining the formation of educational and occupational aspirations among young people.

We compared the prospective first-in-family students to their peers with university-educated parents.

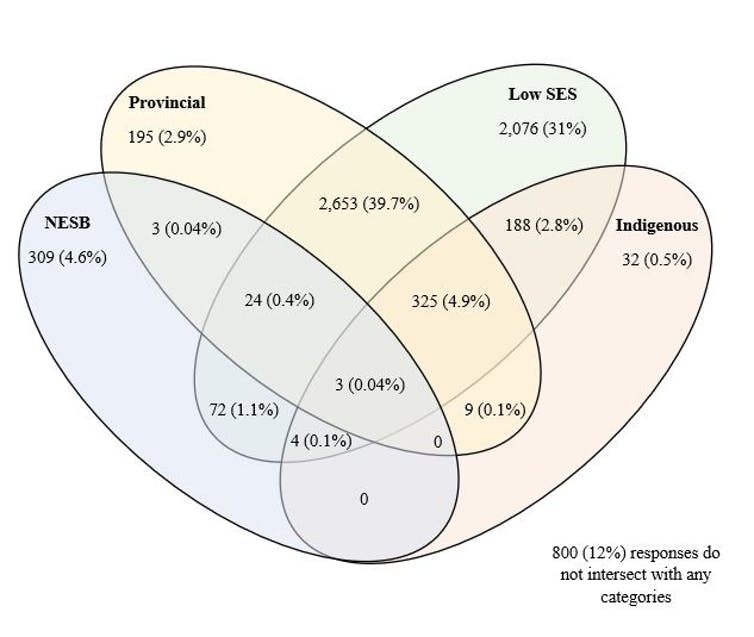

We found many prospective first-in-family students belong to multiple equity categories. They are more likely to identify as Indigenous, come from lower socioeconomic circumstances and live in regional/remote areas than those with university-educated parents.

These prospective first-in-family students often experience overlapping forms of social and economic disadvantage. For example, many were from a low-SES background and lived in a regional or remote area.

However, some first-in-family students don’t belong to any existing equity groups. As a result, current equity interventions could overlook them.

Overlaps of socio-demographic categories for prospective first-generation students. On ‘being first’: the case for first-generation status in Australian higher education equity policy, S. Patfield, J. Gore, N. Weaver (2021)

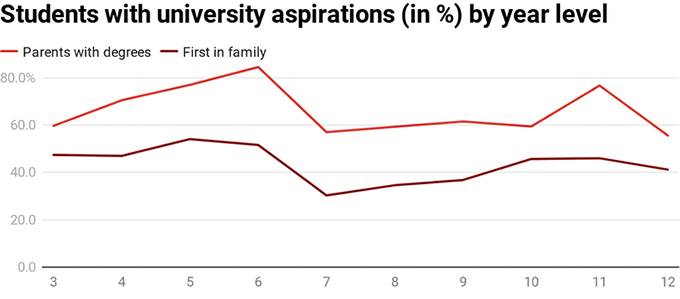

Next, we examined the students’ educational aspirations. Starkly, we found prospective first-in-family students are much less likely to aspire to university than those with university-educated parents. The gap was clear across every stage of schooling.

Even after accounting for other socio-economic and demographic factors, we found young people with university-educated parents were just over 1.6 times more likely to aspire to university than their prospective first-in-family peers. This finding mirrors enrolment trends.

Our findings suggest prospective first-in-family students begin to rule out the idea of higher education from an early age.

Data: On ‘being first’: the case for first-generation status in Australian higher education equity policy, S. Patfield, J. Gore, N. Weaver (2021)

What this means for policy and practice

Our research provides evidence of the need for a targeted focus on supporting first-in-family students to gain access to university.

While first-in-family status intersects with many existing equity categories, it’s an additional form of educational disadvantage that current policy doesn’t cover.

Practically, conversations about university need to occur early in schooling. It’s not a matter of asking young people to “choose” their post-school destination. Instead, they should be exposed to a wide range of possible options before they decide this pathway “isn’t for them”.

Some first-in-family students end up deciding later in life to go to university. That’s why enabling programs are also crucial to help these students get into higher education.

Arguably, first-in-family status should be the quintessential concern of university equity agendas. These students face unacknowledged hurdles in navigating a different pathway from the one their families took.

Their triumph in “being first” should be recognised for the new course it sets in family histories, often against great odds.

Author Bios: Sally Patfield is a Postdoctoral Fellow, Teachers and Teaching Research Centre, Jenny Gore is Laureate Professor of Education, Director Teachers and Teaching Research Centre and Natasha Weaver is a Lecturer in Statistics all at the University of Newcastle