The Australian Coalition government’s position on young people is best captured by the phrase “earning or learning”. If you are under 30, the government expects you to be studying in an educational institute or working for a living.

Leaving the politics aside, the relationship between education and employment is usually a good indicator of labour market health: generally speaking, the more educated you are, the more earning potential you have.

So what happens when this relationship comes undone? Unfortunately, young people have been finding this out the hard way.

For “Gen Y” (born in the 1980s and 1990s), it seems being the most educated generation does not necessarily translate to being the most employed generation. Recently, this fact has been highlighted by the release of the Graduate Outcomes Survey and Employer Satisfaction Survey. Together, these reports capture the mood of the current labour market.

The transition from study to work

The Graduate Outcomes Survey, canvasses graduates four months after graduation, asking them a range of questions. This includes asking graduates about the type of work they do, how much they earn, and how satisfied they are with their employment. It also covers more complex issues, like skills utilisation, demographic inequalities and how much study prepares graduates for work.

The good news is the overall number of undergraduates in full-time employment has risen to 71.8%, up from 68.1% in 2014. The bad news is this is still well below the pre-Global Financial Crisis employment level of 85.2% in 2008.

Worse still, the latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey datashows graduate wages are shrinking over time. For those who graduated between 2006-09, the average weekly wage was A$947.31 in their first year of graduate employment. For those who finished university between 2012-13, the graduate wage shrunk to A$791.58 a week – and that’s before factoring in inflation.

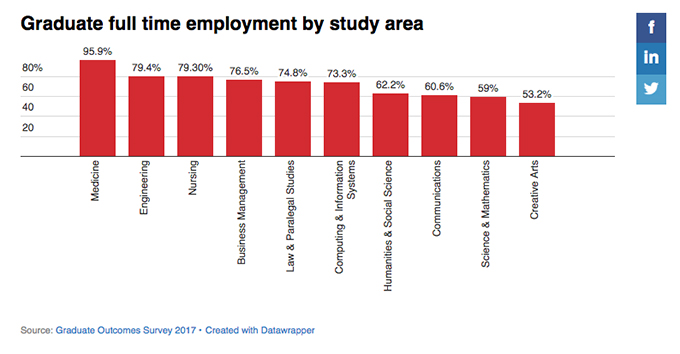

There are also uneven rates of employment, as some areas of study provide better employment prospects than others.

Some of this is unsurprising. Medicine continues to provide full-time employment, while creative arts offers less in the way of traditional employment outcomes. But despite the emphasis on STEM graduates in the government’s innovation agenda, businesses are failing to utilise the existing scientific workforce.

The question of skills utilisation proves to be similarly troublesome.

Two out of three graduates with full-time work reported they took a job unrelated to their study area, due to external labour market factors. These factors include employment relevant to their study not being available and employers wanting graduates to have more work experience, as well as graduates only being able to find part-time or casual work.

Unsurprisingly, part-time work is becoming a more likely employment pathway for graduates. Given that over a third of undergraduates are working part-time, it might be tempting to assume this shift away from full time work reflects a choice made by young people.

Contrary to claims young people want or need “flexibility” (like those made by business leaders such as Myer’s David Umbers and PwC’s Luke Sayers), recent research shows Gen Y continue to desire full-time, secure employment just like previous generations.

The view from the board room

Turning to the Employer Satisfaction Survey, 84% of supervisors reported overall satisfaction with the quality of graduates who worked for them. While 42% of graduates reported their skillset wasn’t relevant to their employment, 64% of their supervisors saw relevant skillsets in graduates. Similarly, 93% of supervisors believed the degrees obtained by their employees prepared them well for employment.

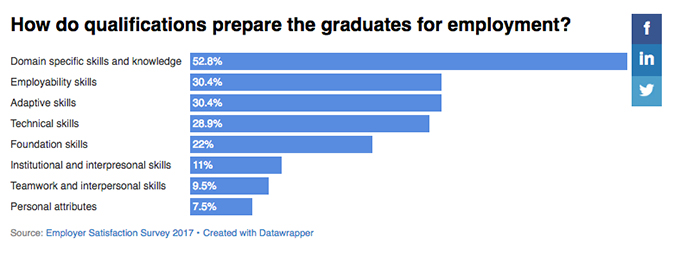

But employers felt some aspects of undergraduate qualifications prepared graduates for employment more than others.

Domain specific knowledge is the most valuable skill qualifications offer employers. Conversely, it appears employers don’t see qualifications as offering much in the way of technical, adaptive, or foundational skills.

Interestingly, none of the elite Group of 8 universities placed in the top five for employer satisfaction. This honour went to James Cook University, University of Notre Dame, University of the Sunshine Coast, Bond University and the University of Wollongong. Only the University of Queensland and the University of Melbourne made it into the top ten.

It appears prestige is not rated as highly by employers as technical skillsets and domain specific knowledge.

Where to from here?< /h4>

While there are certainly areas universities could improve to increase employer satisfaction, employers seem happy with the quality of graduates. The problem doesn’t appear to be with the relevance of qualifications and skillsets to employment, but rather with the scarcity of employment.

So, if young people are learning, whose responsibility is it to make sure they’re earning?

More and more students are graduating every year, but businesses and the public service aren’t providing enough graduate level opportunities.

Given the commitment Education Minister Simon Birmingham has shown to cutting university funding, it seems universities will have to do more with less. If this legislationcomes into effect, the government could reinvest those savings in graduate programs that offer more technical training and vocational experience.

Particularly given the lack of opportunities offered to science and maths graduates, an increase in funding to the CSIRO and research institutes could provide for greater utilisation of STEM graduates.

Ultimately, we need to learn from both reports and design policy that gives young people a chance to start earning.

Author Bio: Shirley Jackson is a PhD Candidate in Political Economy at the University of Melbourne