Reports of Facebook moderators’ appalling working conditions have been making headlines worldwide.

Workers say they are burning out as they moderate vast flows of violent content under pressure, with vague, ever-changing guidelines. They describe unclean, dangerous contractor workplaces. Moderators battle depression, addiction, and even post-traumatic stress disorder from the endless parade of horrors they consume.

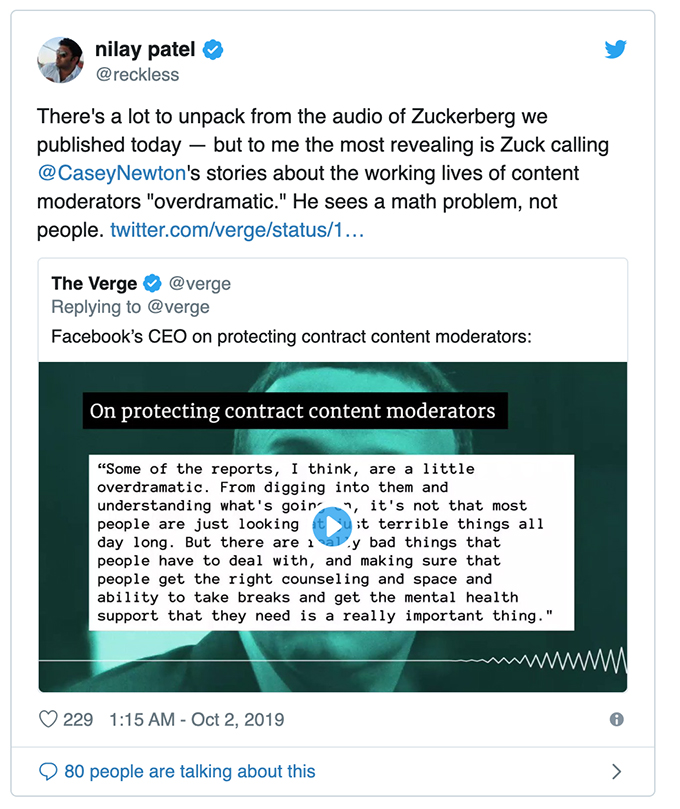

Yet in leaked audio recently published by The Verge, Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg can reportedly be heard telling his staff that some of these reports “are, I think, a little over-dramatic”.

Out of touch and dismissive

While Zuckerberg acknowledges that Facebook moderators need to be treated humanely, overall he comes across in the recording as a person who sees human suffering as “a math problem”, as The Verge’s editor-in-chief Nilay Patel suggested on Twitter.

Zuckerberg’s response is troubling on several fronts, not least in minimising the impact of moderation on those who do it. It also works to discredit those who blow the whistle on poor working conditions.

In dismissing the real risks of poorly paid, relentless content moderation and implying that moderators who call out issues are “over-dramatic”, Zuckerberg risks compounding moderators’ trauma.

This is a result of what American psychologists Carly Smith and Jennifer Freyd call “institutional betrayal”, where the organisation we trust to support us, doesn’t. Worse still, this behaviour has also been shown to make people doubt their decision to report in the first place.

We also contacted Facebook about Zuckerberg’s comments and asked them to confirm or deny the working conditions of their moderators. They gave us the following statement:

We are committed to providing support for our content reviewers as we recognize that reviewing certain types of content can be hard. That is why everyone who reviews content for Facebook goes through an in-depth, multi-week training program on our Community Standards and has access to extensive support to ensure their well-being, which can include on-site support with trained practitioners, an on-call service, and healthcare benefits from the first day of employment. We are also employing technical solutions to limit exposure to graphic material as much as possible. This is an important issue, and we are committed to getting this right.

While Zuckerberg and Facebook acknowledge that moderators need access to psychological care, there are major structural issues that prevent many of them from getting it.

Bottom of the heap

If the internet has a class system, moderators sit at the bottom – they are modern day sin-eaters who absorb offensive and traumatic material so others don’t have to see it.

Most are subcontractors working on short-term or casual agreements with little chance of permanent employment and minimal agency or autonomy. As a result, they’re largely exiled from the shiny campuses of today’s big tech companies, even though many hold degrees from top-tier universities, as Sarah T. Roberts discusses in her book Behind The Screen.

As members of the precariat, they are reluctant to take time off work to seek care, or indicate they are unable to cope, in case they lose shifts or have contracts terminated. Cost of care is also a significant inhibitor. As Sarah Roberts writes, contract workers are oftenoften not covered by employee health insurance plans or able to afford their own private ccover.

This structural powerlessness has negative implications for workers’ mental health, even before they start moderating violent content.

Most platform moderators are hired through outsourcing firms that are woefully unqualified to understand the nuances of the job. One such company, Cognizant, reportedly allows moderators nine minutes each day of “wellness time” to “process” abhorrent content, with repercussions if the time is used instead for bathroom breaks or prayer.

Documentaries like The Moderators and The Cleaners reveal techno-colonialism in moderation centres in India, Bangladesh and the Philippines. As a whole, moderators are vulnerable humans in a deadly loop – Morlocks subject to the whims of Silicon Valley Eloi.

Organising for change

Despite moderators’ dismal conditions and the dismissiveness of Zuckerberg and others at the top of the tech hierarchy, there are signs that things are beginning to change.

In Australia, online community managers – professionals who are hired to help organisations build communities or audiences across a range of platforms, including Facebook, and who set rules for governance and moderation – have recently teamed up with a union, the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance, to negotiate labour protections.

This has been done through the Australian Community Managers network (ACM), which also provides access to training and peer support. ACM is also working with like-minded organisations around the world, including Bundesverband Community Management in Germany, Voorzitter Vereniging Community Management in the Netherlands, The Community Roundtable in the United States, and nascent groups in India and Vietnam.

These groups are professional communities of practice and union-like surrogates who advocate for their people, and champion their insights and perspectives.

As this movement grows, it may challenge the tech industry’s reliance on cheap, unprotected labour – which extends beyond moderation to countless other areas, including contract game development and video production.

The YouTubers’ union and beyond

Workers in the gaming industry are also starting to push back against frameworks that exploit their time, talent and, invariably, well-being (as illuminated by Hasan Minaj on Patriot Act). In Australia Gaming Workers Unite is mobilising games workers around issues of precarious employment, harassment (online and off), exploitation and more.

And in Europe YouTubers are joining the country’s largest metalworkers’ union, IG Metall, to pressure YouTube for greater transparency around moderation and monetisation.

Although Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t seem to understand the human challenges of internetworked creativity, or the labour that enables his machine to work, he may yet have to learn. His remarks compound the material violence experienced by moderators, dismiss the complexity of their work and – most crucially – dismiss their potential to organise.

Platform chief executives can expect a backlash from digital workers around the world. The physical and psychological effects of moderation are indeed dramatic; the changes they’re provoking in industrial relations are even more so.

Author Bios: Jennifer Beckett is a Lecturer in Media and Communications at the University of Melbourne, Fiona R Martin is a Senior Lecturer in Convergent and Online Media and Venessa Paech is a PhD Candidate, researching AI and online communities both at the University of Sydney