This summer I worked on the Greenland ice sheet, part of a scientific experiment to study surface melting and its contribution to Greenland’s accelerating ice losses. By virtue of its size, elevation and currently frozen state, Greenland has the potential to cause large and rapid increases to sea level as it melts.

When I returned, a nonscientist friend asked me what the research showed about future sea level rise. He was disappointed that I couldn’t say anything definite, since it will take several years to analyze the data. This kind of time lag is common in science, but it can make communicating the issues difficult. That’s especially true for climate change, where decades of data collection may be required to see trends.

A recent draft report on climate change by federal scientists exploits data captured over many decades to assess recent changes, and warns of a dire future if we don’t change our ways. Yet few countries are aggressively reducing their emissions in a way scientists say are needed to avoid the dangers of climate change.

While this lack of progress dismays people, it’s actually understandable. Human beings have evolved to focus on immediate threats. We have a tough time dealing with risks that have time lags of decades or even centuries. As a geoscientist, I’m used to thinking on much longer time scales, but I recognize that most people are not. I see several kinds of time lags associated with climate change debates. It’s important to understand these time lags and how they interact if we hope to make progress.

Agreeing on the goal

Changing the basic energy underpinnings of our industrial economy will not be easy or cheap, and will require broad public support. Today nearly half of Americans – presumably including President Trump, based on his public comments – do not believe that humans are the primary cause of modern rapid climate change. Others admit that humans have contributed, but may not support strict regulations or big investments in response.

In part, these views reflect the influence of special interest groups who benefit from our high-carbon “business as usual” economic system. But they also reflect the complexity of the problem, and the difficulty scientists have in explaining it. As I point out in my recent book on how we think about disasters, statements made by scientists in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s about global warming were often vague and full of caveats, which made it easy for climate change skeptics to forestall action by emphasizing how uncertain the picture was.

Fortunately, scientists are improving at communication. The increasing frequency of coastal flooding, summer heat waves and droughts could also help to change minds, but it may take a few more decades before a solid majority of Americans supports high-level action.

Earth’s average temperature has risen over 1 degree Fahrenheit in the past century. It is projected to rise an additional 3°F to 10°F over the next 100 years.

Designing cleaner technologies

It will also take time for technological developments to support our transition to a low-carbon energy future. Here, at least, there is reason for optimism. A few decades ago renewable energy sources such as wind and solar seemed unlikely to replace a significant fraction of carbon-based energy. Similarly, electric vehicles seemed unlikely to meet a significant share of our transportation needs. Today both are realistic alternatives.

This year wind and solar power hit 10 percent of U.S. electricity generation for the first time. Electric vehicles and hybrids are also becoming more common. The recent advent and rapid adoption of LED lighting could start to have an impact on our electrical consumption.

Thanks to these developments, humanity’s carbon footprint will look quite different in a few decades. Whether that’s quick enough to avoid 2 degree Celsius of warming is not yet clear.

Funding the transition

Once we finally decide to make a low-carbon transition and figure out how to do it, it will cost trillions of dollars. Capital markets can’t provide that sort of funding instantaneously.

Consider the cost of upgrading just the U.S. housing market. The United States has approximately 125 million households, of which about 60 percent (75 million) own their own homes. The majority of these are single-family residences.

If we assume that at least 60 million of these residences are single-family homes, duplexes or townhomes where it is feasible for residents to upgrade to solar photovoltaic power, then equipping just half (30 million homes) with a standard solar energy package and battery storage, at a cost of about US$25,000 per household, would cost nearly a trillion dollars. Our economy can support this level of capital investment over one or two decades, but for most of the world it’s going to take longer.

Solar Charging Station for Electric Vehicles at Phillips Chevrolet, Frankfort, Illinois. New energy technologies require infrastructure to support them. Phillipschevy

The natural carbon cycle

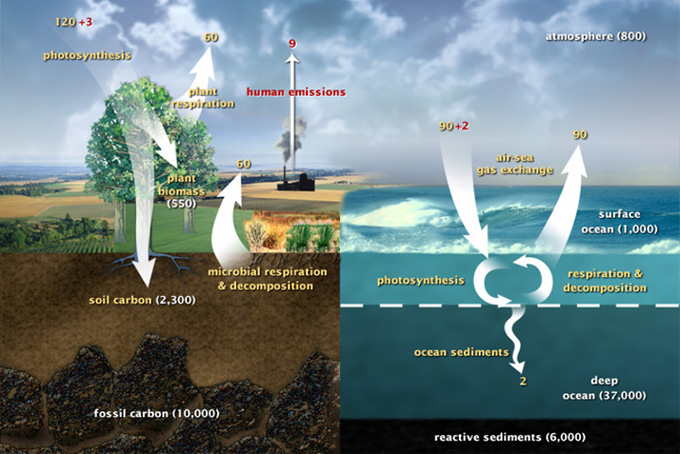

Our ability to add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere greatly exceeds nature’s ability to remove it. There is a time lag between carbon emission and carbon removal. The process is complicated, with multiple pathways, some of which operate over centuries.

For example, some atmospheric carbon dioxide at the ocean’s surface dissolves into seawater, forming carbonate ions. Meanwhile, rainfall weathers rocks on land, slowly breaking them apart and washing calcium and magnesium ions into rivers and streams and on into the oceans. These materials combine into minerals such as aragonite, calcite or dolomite, which eventually sink and become entombed in sedimentary layers at the bottom of the ocean.

But since this process plays out over many centuries, most of the carbon dioxide that we put into the atmosphere today will continue to heat the world for hundreds to thousands of years.

Earth’s carbon supply constantly cycles between land, atmosphere and oceans. Yellow numbers are natural fluxes, and red are human contributions in gigatons of carbon per year. White numbers indicate stored carbon. NASA Earth Observatory

Today the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is just over 400 parts per million, rising by about 3 ppm yearly. Given the political, technological and economic time lags that we face, it’s likely that we will hit at least 450-500 ppm before we can seriously curtail our carbon emissions. The last time Earth’s atmosphere contained this much carbon dioxide was several million years ago, during the Pliocene era. Global temperatures were much higher than 2°C above today’s average, and global sea level was at least 6 meters (nearly 20 feet) higher.

We haven’t seen comparable temperature or sea level increases so far because of time lags in Earth’s climate response. It takes a while for our elevated carbon dioxide levels to trigger impacts on this scale. Given the various time lags that are in play, it is quite possible that we have already exceeded the 2°C rise over preindustrial temperatures – a threshold most scientists say we should avoid – but it hasn’t shown up on the thermometer yet.

We may not be able to predict exactly how much future temperatures or sea levels will rise, but we do know that unless we curb our carbon emissions, our planet will be a very uncomfortable place for our grandchildren and their grandchildren. Large-scale social changes take time: they are the sum of many individual changes, in both attitudes and behaviors. To minimize that time lag, we need to start acting now.

Author Bio: Timothy H. Dixon is Professor, Geology and Geophysics, Natural and human-caused hazards, sea level rise and climate change at the University of South Florida