Career-related motivations are among the most important factors in Australian students’ decision to undertake higher education. This means universities must demonstrate their graduates’ ability to find work when seeking to recruit students in an increasingly competitive tertiary education marketplace. Our research shows double degrees (students study for two degrees at once) can greatly improve new graduates’ prospects of finding full-time work.

Some combinations increased the success rate by as much as 40% compared to students with a single “generalist” degree. The gains were biggest for students in the arts and sciences.

Yet double degrees are often overlooked as a way to improve graduates’ employability. Universities’ efforts to improve graduates’ employment outcomes generally focus on curricular and extracurricular programs such as work-integrated learning, internships and workshops. These will continue to grow in importance, as graduates are increasingly competing in a labour market where the supply of high-quality graduate jobs is failing to keep up with the production of graduates.

However, recent Monash University research, as yet unpublished, shows something even more fundamental to universities — the structure of our educational offerings – can have a major impact on graduates’ employment outcomes. In particular, offering double degrees for undergraduates can make a significant difference.

Why offer double degrees?

Monash University has had a long-term focus on strengthening its double-degree offerings. The aim is to give students a more versatile skill set that increases their career flexibility and opportunities.

This focus on double degrees involves a huge resource commitment. It shapes many facets of Monash’s operations, from the design of our courses to the physical layout of our campuses.

Our approach is designed to prepare graduates to adapt to varying labour market demand for skills across different academic disciplines. The demand for specific disciplines expands and contracts based on economic forces that are often hard to predict.

A problem graduates then face is that the skills acquired in one academic discipline are not universally transferable. A student completing a law degree, for example, might be highly capable, but would struggle to leverage their skills (at least without substantial retraining) to become an engineer if that discipline was in greater demand. To improve employment outcomes, then, graduates need a broad skill set that allows them to be productive across different sectors.

What did the research find?

When the results of the most recent national Graduate Outcomes Survey were released, a key question for Monash was whether our investment in double degrees had helped graduates weather the labour market shocks of the pandemic. The national employment rate for new graduates fell from 72.5% in 2019 to 69.1% in 2020.

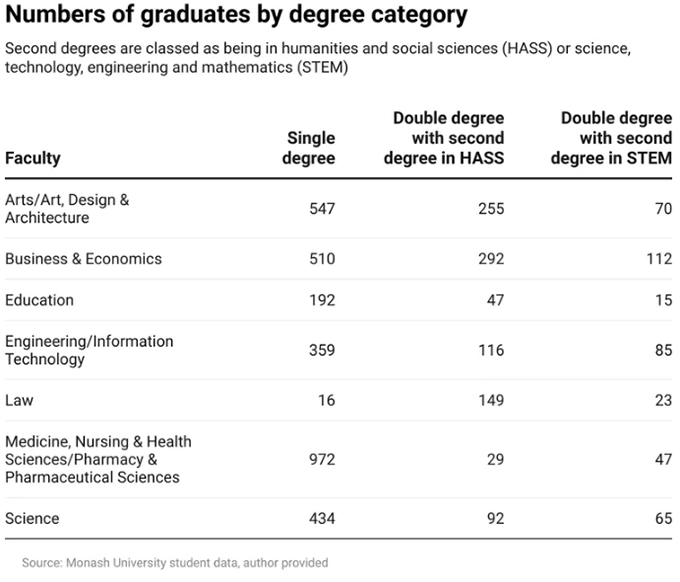

We examined undergraduate employment rates across Monash’s faculties based on whether students had undertaken double degrees. This yielded a number of interesting findings.

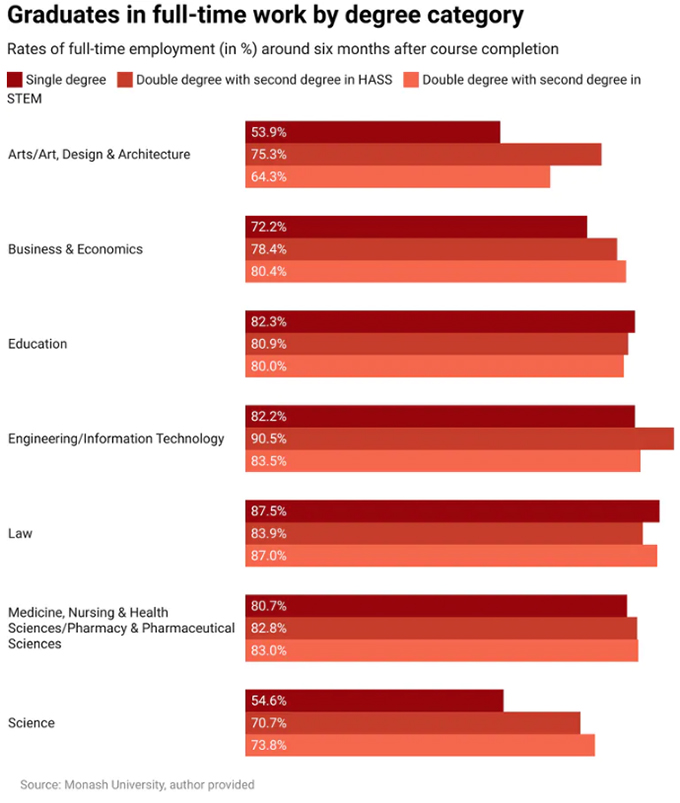

First, double-degree students have significantly higher full-time (FT) employment rates around six months after course completion for second degrees in humanities and social sciences (HASS) and in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

Second, we found this effect is greatest for so-called “generalist” degrees. These do not have career pathways as clearly defined as other disciplines. Specifically, graduates from courses in science and in arts/art, design and architecture were much more likely to find full-time work if they completed a double degree.

The effect is less pronounced for more vocationally oriented courses, such as education, engineering (paired with STEM) and law (paired with HASS). This is not to suggest double degrees are not valuable for students in these disciplines. Double degrees allow students to keep their options open, insulating them somewhat from the notoriously unpredictable supply and demand for graduate skills.

Isn’t it just the kind of person who does double degrees?

These results prompted the question: are double degrees responsible for these strong employment outcomes, or are the people who study double degrees inherently more employable to begin with? In other words, do double degrees improve graduate employability, or do they merely reflect graduate employability?

To investigate this, we modelled graduate employment based on double-degree completion and students’ background characteristics. The effect held — the advantage associated with double degrees does not appear to be simply an artefact of the type of individual who chose to enrol in one.

Ultimately, Monash’s commitment to double degrees played a substantial role in achieving the highest full-time undergraduate employment rate of Victorian-based universities in 2020.

What explains the employability benefit?

So, why do double degrees give graduates such an advantage in the labour market? This is a much harder question to answer.

There is likely to be a human capital benefit, in that double-degree holders have gained a greater depth and breadth of skills than those with single degrees. The labour market recognises this through a greater likelihood of receiving a job offer.

There is likely also to be a signalling benefit as employers, faced with very little information on the productivity of the graduates sitting opposite them in job interviews, use the double degree as a sign of their productivity. It’s likely they make offers to graduates on this basis.

In a practical sense, the mechanism behind the effect of double degrees on employability is less important than the existence of the effect itself. Whether the effect is due to human capital factors, signalling or their combined effect, double degrees offer a significant employment benefit to the students who complete them and to the universities that develop and promote them.

Author Bios: David Carroll is a Researcher and Senior Manager, Strategic Information, Kris Ryan is Pro Vice-Chancellor (Academic) and Susan Elliott is Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Vice-President (Education) all at Monash University