“Educate in equality so you don’t miss a single talent due to lack of opportunities.”

Josefina Aldecoa, Story of a Teacher, (1990).

Every March 8 we commemorate the International Women’s Day declared by the UN in 1975. That important day for feminism has not only become a memory for textile workers who demonstrated in New York in 1857 claiming better conditions labor, but also in Spain meant the opening of women to public university education.

From 1888 to 1910

On March 8, 1910 , the enrollment of women in public university degrees was authorized . Before this date, this fact so consolidated in our current society was an adventure for half of the population: The Royal Order published on June 11, 1888 admitted only the access of women to private universities by authorization of the Council of Ministers

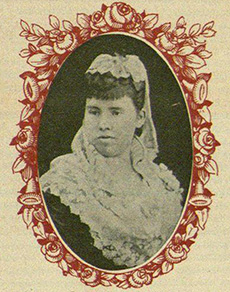

The first woman to access university studies was María Elena Maseras Ribera , who began her medical degree in Barcelona, in the academic year 1872-1873.

The first woman to access university studies was María Elena Maseras Ribera , who began her medical degree in Barcelona, in the academic year 1872-1873.

In the period from 1888 to 1910, the life of the students was conditioned by their sex and the freedom of movement within the university was completely limited. Even one of the great pioneers of Spanish feminism, Concepción Arenal , had to disguise herself as a man in order to pursue her law studies at the University of Madrid.

Between 1882 and 1910, 36 women, 0.17% of university students, managed to finish their studies in the faculties and fight for the recognition of their degrees to be able to practice professionally, as was the case of María Elena Maseras and Dolores Aleu.

From 1910, and until 1935, with the new regulations, the number of women who began their studies in public universities increased significantly. Of the 21 students enrolled in the 1909-1910 academic year , more than 2,000 women were transferred in 1935, so the change in mentality in women’s access to education materialized significantly.

Situation in 2019

These percentages have nothing to do with the current ones, according to data presented by the Ministry of Education. In the 2018-2019 academic year , 55.2% of university students were women. Preferred careers among them follow a trend relatively similar to that of the previous century, when medicine and law were the favorites in the early 1900s.

Currently, the most requested careers are: Education, where 77.7% of the students are women, Health and social services (71.4%) and Social Sciences, journalism and documentation (61.9%).

There is no doubt, therefore, that the regulations approved by the Count of Romanones , head of the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts of Spain in 1910, opened a new academic path for women.

Not only that: the openness to new knowledge made them change the domestic environment for the public environment. Bachelor’s degrees allowed women’s access to teaching positions at all levels of education and their visibility in many other professions. The gender education gap that allowed men access to education for centuries only began to disappear.

Miss Residence

Another important fact related to the access of women to the university world was the creation, by the Board of Expansion of Studies (JAE) in 1915, of the Residence of Young Ladies in Madrid , homologous of the Residence of male Students .

The female Residence was directed by María de Maetzu . This center became a space for constant dialogue and learning for the students who were staying there, such as Victoria Kent or Clara Campoamor . But, in addition, it hosted numerous conferences in which women from all over the world presented their ideas, including Marie Curie or Gabriela Mistral .

Both this recognized female residence and the access of women to the university environment were forged in the movement for women’s education that began Fernando de Castro between 1869 and 1873. De Castro was the humanist rector of the University of Madrid and among his great contributions there is the creation of an Artistic and Literary Athenaeum, the Association for the Teaching of Women, created in 1870, and the holding of a circle of conferences aimed at women’s education.

With this incipient interest in the access of women to higher education and knowledge beyond the upbringing of children, their capacity for reason and knowledge was recognized, equal to that of men, and their preparation to qualify for specialization of the liberal professions. Thus, women’s access to the world of work began and cultural foundations were laid for equality between men and women.

In conclusion, the early twentieth century marked a before and after in women’s access to higher education. Despite the clear patriarchal character that prevailed in all spheres of Spanish society, in 1910 the Spanish university began to transform and this also modified gender relations in the educational and professional fields.

Author Bio: Alicia Alvarado Escudero is Professor of the Master in Educational Processes of Teaching Learning at Nebrija University