2021 is when the impacts of COVID-19 really start to take their toll on universities, as more than 140,000 international students seek to return to study in Australia. My new analysis, presented in this article, reveals that if one in five international students don’t re-enrol, the loss of revenue would plunge half of all Australian universities into financial turmoil or budget deficit. While the impacts of COVID are unprecedented, modelling universities’ financial resilience shows which institutions fare better and why.

International students generated A$10 billion in fee revenue for universities in 2019. This in turn drives jobs, local industry, research and Australia’s reputation as a destination for quality higher education.

Recent modelling by the Mitchell Institute estimated more than 300,000 fewer international students would be studying inside Australia by mid-year, if travel restrictions continued.

Universities employ more than 130,000 staff at 200 campus locations across Australia. Many of these jobs could be at risk. Universities Australia figures show at least 17,300 have already been lost.

Revenue and reputation: a self-reinforcing cycle

In total, 32% of all full-time-equivalent enrolments at Australian universities are international students. About a quarter (24%) of all university revenue comes from these students. Universities’ operating revenue fell 4.9% in 2020, with an estimated 5.5% fall to come in 2021.

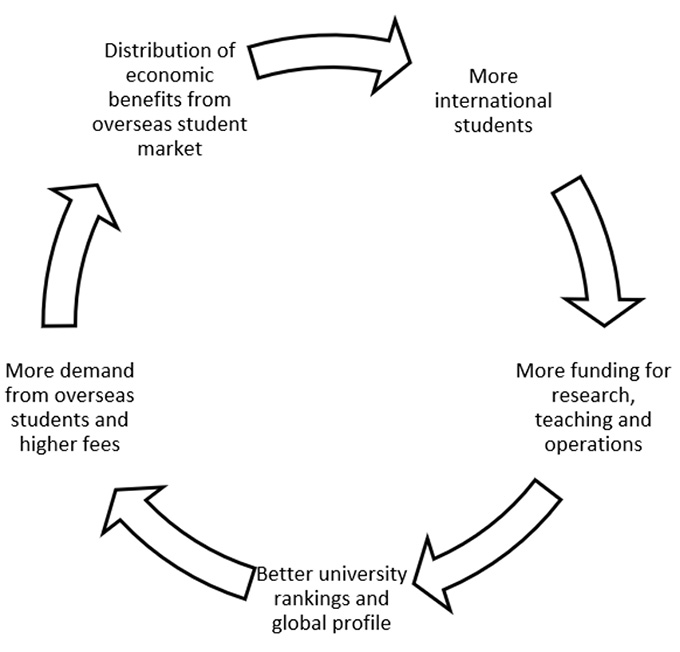

International student fees are correlated with university rankings but are also a self-reinforcing cycle: more international students generate more revenue to fund more research, which in turn leads to better rankings and more demand.

International student revenue increases university resources, which enhances reputation, which in turn attracts more international students. Author provided

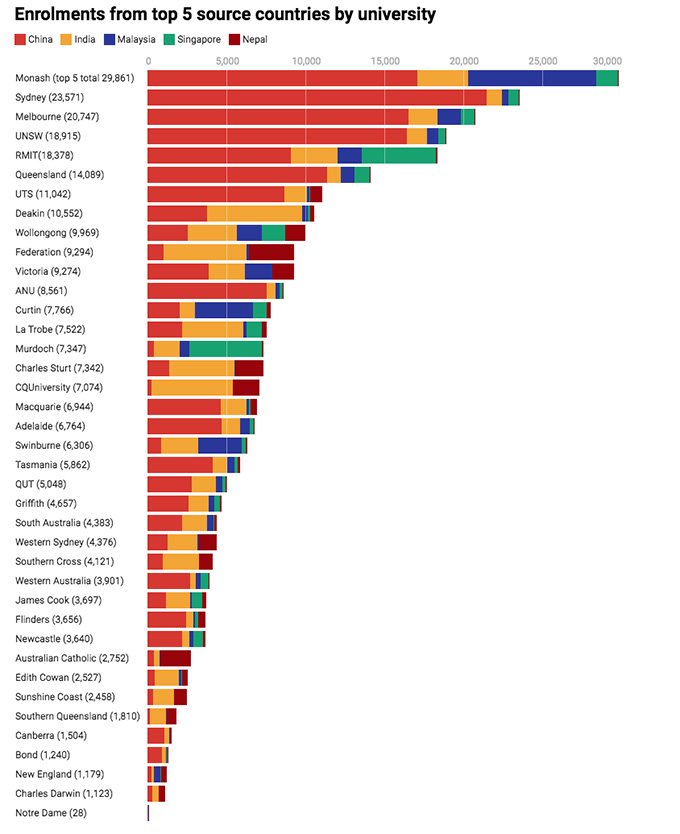

Another risk factor for universities is the concentration of enrolments from just a few source countries. They are also concentrated in the largest institutions. One in four international students (25%) study at one of these five universities: Monash, RMIT, Melbourne, Sydney or UNSW.

The leading source of international students in Australia is China, with 36% of these students. It’s followed by India (14%), Malaysia (7%), Singapore (5%) and Nepal (4%). Just one or two geographic markets dominate international enrolments at most universities.

International students aren’t the only risk factor

The worst-hit universities may be those with small pre-COVID operating margins and high reliance on concentrated international student revenue.

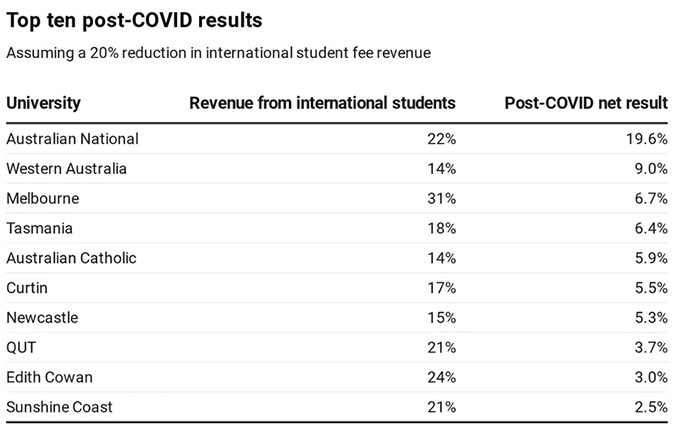

My analysis shows a 20% fall in international student fee revenues would leave 22 universities in deficit or on the brink with a net operating result (revenue minus expenses) of 1% or less.

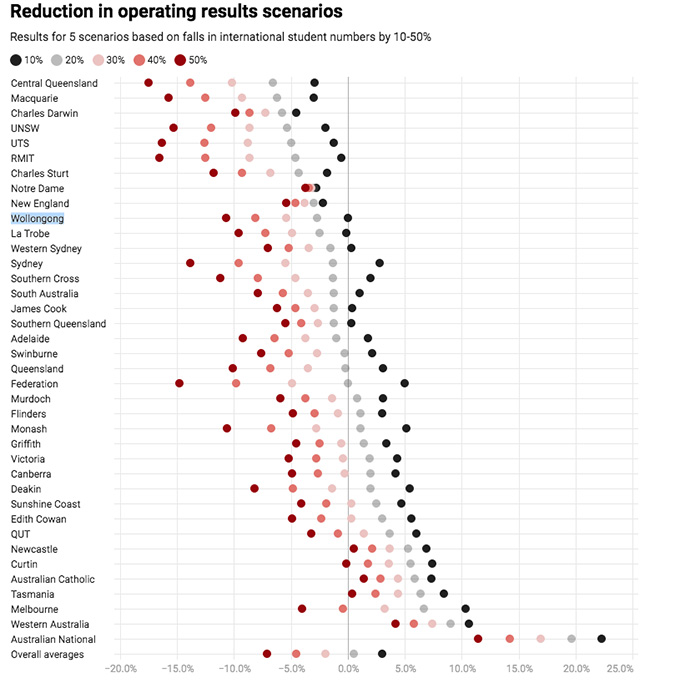

Those with a higher reliance on international students, less diverse revenue streams or a lower return on equity fare worse in the post-COVID modelling. The chart below shows the impact on university net operating results of five scenarios involving decreases in international students by 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% and 50%.

The net result decreases more dramatically for those with both a high reliance on international students and a limited operating buffer. In other words, the risks already existed – COVID amplified them.

Universities need a buffer to absorb shocks

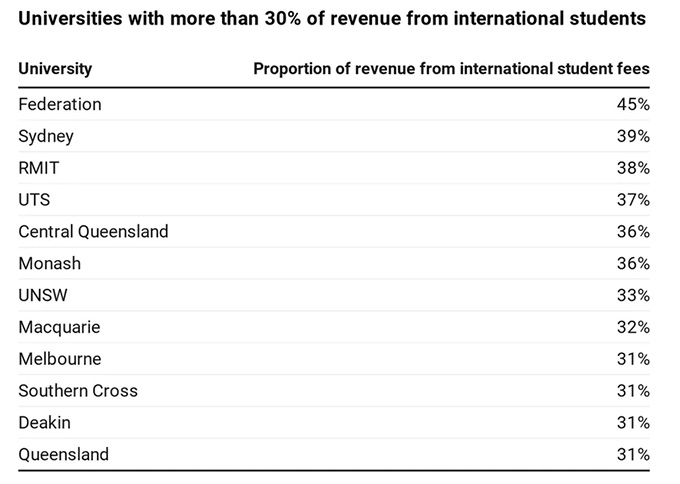

Many Australian universities rely heavily on revenue from international students as part of their business model and global profile. Twelve rely on international student fees for more than 30% of their total income.

While all the universities in the above table are registered not-for-profits, they need to remain financially sustainable. Any organisation involved in high-stakes global markets should have a buffer against rare and unexpected shocks such as the COVID pandemic. A requirement for financial buffers was legislated in the US following the global financial crisis but still remains a vexed issue.

The average net pre-COVID operating result for Australian universities was a healthy 5.6%. However, several started the year with a result of less than 1%. These universities included Charles Darwin (-3.1%), Notre Dame (-2.6%), New England (-1.4%), Macquarie (0.14%), Central Queensland (0.71%) and Charles Sturt (0.77%).

These results raise important questions for university boards. What is a responsible operating result considering the risks of the business and the markets in which it operates? Was “pandemic” already identified in risk registers? And what was done about it?

Significant revenue write-downs leave institutions with only a few levers to buffer the COVID shock while minimising risks to quality.

Author analysis of modelling using data from Department of Education, Skills and Employment, Finance tables

On average, the above top ten universities generate 20% of their revenue from international student fees. The sector average is 24%.

The University of Melbourne gets 31% of its revenue from international student fees. That’s higher than the average, but its very healthy pre-COVID operating result of 13.9% provides breathing space.

Newcastle, QUT, Edith Cowan and the Sunshine Coast are in the top ten universities, but under this model have a potential post-COVID result of less than the sector average of 5.6%. Their risk exposure to international student fee revenue is still average or lower.

How should universities respond?

Three main conclusions can be drawn.

First, to underpin their financial sustainability and avoid risks to quality, universities must consider not only their reliance on international student fee revenue and market concentration, but also strategies to understand and define their appetite for risk.

Second, the model for online education when travel across borders is limited could be a long-lasting effect of COVID. Long-term strategies and regulatory practices to deal with this “new normal” of global higher education will be needed, beyond temporary regulatory flexibility.

Third, disruption to higher education is here to stay. Waiting for a time when the view on the horizon is clear for all to see may be too late.

Global higher education requires a new organisational ambidexterity. That means universities must revisit core operating models, re-imagine future potential and succeed on the disruptive edge.

Author Bio:Omer Yezdani is Director, Office of Planning and Strategic Management at the Australian Catholic University