In an effort to find a more engaging way to present child development to new psychology students, I decided to use a book about a little orphan boy who later discovers he is a wizard.

As the course evolved over the years, I found another benefit of using J.K. Rowling’s famous books: The story of Harry Potter, who lost both his parents to traumatic deaths at an early age, offers new college students insights that might help them better appreciate their own resilience.

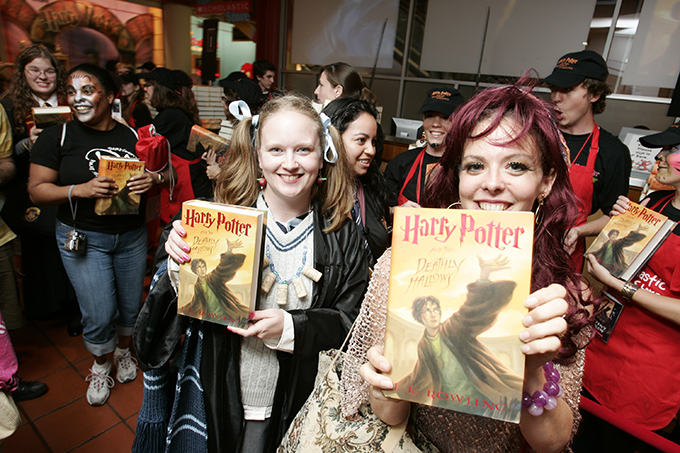

As the 20-year anniversary of the debut of Harry Potter in the U.S. draws near, I believe that the course I developed more than a decade ago is still relevant for today’s first-year students, many of whom first got introduced to Harry Potter during their own childhoods.

The class I teach at Vanderbilt University – simply titled “Harry Potter and Child Development” – uses the science of developmental psychology to deepen students’ understanding of the behavior of Harry, Hermione and Ron – the central characters of the books – and the adults in these characters’ lives.

Near the end of the semester, I include topics such as depression, perfectionism, the need for a growth mindset and tolerance for differences – challenges that students entering college must grapple with to be successful.

How it all began

The seeds for the development of this course began back when I – like many parents in the late 1990s – spent many evenings reading the Harry Potter books to my then-young son.

Most parents probably did not interrupt their reading of the Harry Potter books as I did when I would dog-ear a page or jot a note in the margin. Trying my son’s patience, I’d grab a pencil and write notes such as: “Great example of Harry as a resilient child.” Or I’d note how Harry and Tom Riddle – the two orphans in the story – turned out, compared to institutionalized orphans in Eastern Europe.

When I came upon the part about Lily Potter instinctively stepping in front of a killing curse to save her infant son, imbuing Harry with an “old magic” that continued to protect him from the forces of evil, I wondered in my notes if that could be a metaphor for the lasting effect of secure parental attachment? Were Harry’s depression – during Dementorattacks – and his adolescent anger the result of hormones? Or were they expressions of childhood grief, age-appropriate responses to traumatic death?

We delve into all these questions and more in the class.

Resilient Harry Potter

For instance, on the topic of childhood resilience, I help the students make connections between Harry Potter and a famous 30-year longitudinal study by Emmy Werner that followed 698 children from a small Hawaiian island from before they were born, through childhood and into adulthood.

With good parenting, most of the children in the study who suffered birth complications or early trauma overcame any deficits. On the other hand, those who experienced some early trauma and whose families had major problems, such as divorce or substance abuse, tended to end up with long-term problems. They did poorly in school, got in trouble with the law, and had a much higher incidence of mental illness than their peers. But there was a twist to the story. Surprisingly, a third of the children with challenges from both nature and nurture “grew into competent young adults who loved well, worked well and played well.”

Werner looked back at her data to identify why some children were “resilient.” She discovered that resilient children tended to be intelligent, or talented in some way. They tended to view school as a “home away from home” where they could feel safe. They were spunky or charming, with personalities that attracted adult attention. Despite their troubled upbringing, resilient children had some adult in their lives – a coach, teacher or minister – who served as a mentor. And they ended up successful adults.

Harry Potter seemed to fit the description of one of Werner’s resilient children in more ways than one. He had just 15 months to develop a secure attachment with his parents before their traumatic deaths. He then lived with relatives who abused him physically and emotionally. Yet he entered Hogwarts School, his “home away from home,” as a smart, spunky 11-year-old who had not been crushed by his experiences. Harry’s modest, charming personality drew mentors to him who filled the roles of surrogate family members, including Hagrid, the Weasleys and Sirius Black. At school, professors McGonigall, Lupin and Dumbledore nurtured Harry’s growing skills and talents. The loving oversight of all these mentors helped Harry grow into a successful adult and the hero of the story.

The psychological value of reading fiction

Research supports the idea that reading literary fiction can affect how readers think and act. Fiction offers a simulation of social life that challenges readers to figure out characters’ motives and points of view.

Fiction also has the power to foster empathy and change attitudes. The immersive experience of using one’s imagination to understand characters in a fictional world – particularly those different from us, but with whom we can identify – can lessen prejudice. Imagination, J. K. Rowling said in her 2008 Harvard commencement address, is “the power that enables us to empathize with humans whose experiences we have never shared.”

The students in my course are encouraged to note when Harry Potter’s development diverges from expected outcomes based on research. Realistically, an orphaned infant left in the care of people like the Dursleys would be unlikely to become our hero – if he survived at all. Yet Rowling’s astute observations about humans and their behavior – rich descriptions that prompted my note-taking back when I used to read Harry Potter books to my son – also offer college students psychologically realistic characters that capture their hearts while educating their minds.

Author Bio: Georgene Troseth is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Vanderbilt University

Author’s Note: Neither this article nor the college course mentioned herein were prepared, authorized or endorsed by J. K. Rowling, the publishers or distributors of the Harry Potter books, or the creators, producers or distributors of the Harry Potter movies.