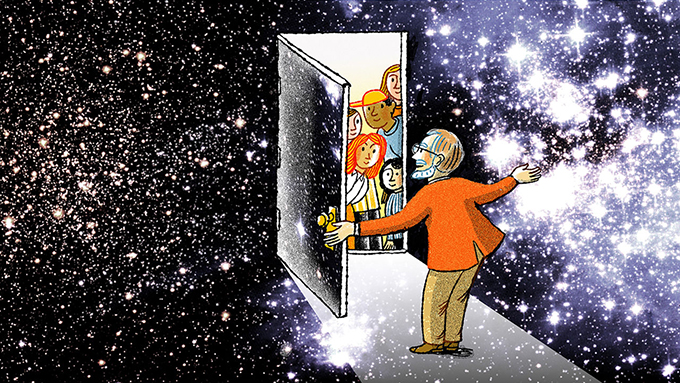

Astronomy has some advantages over other branches of science to reach students easily. Also to awaken their interest in scientific knowledge in general and contribute to their training as future citizens.

The pleasure of observing the sky and the striking nature of the images offered by large telescopes, or the possibility of finding answers to the great questions of humanity, have made it occupy a good space on the popularization shelves of bookstores.

In addition, there are many amateurs who even contribute with their observations to increase knowledge, having what is possibly the most diffuse barrier between the professional and the amateur world .

It is an exciting science, yes, but it also presents some difficulties in teaching it in the classroom. For example, scales very far from human experience are handled and their historical development is one of the most complex in science.

We live with our backs to the sky

Furthermore, our society lives with our backs to the sky, as we no longer depend on it for our survival – although the dangers of space debris, collision with an asteroid or space weather are there. To this we must add that light pollution prevents us from contemplating it in all its beauty.

These difficulties are, in turn, possibilities for students to develop certain scientific skills. Estimates, observation skills, questions about the nature of science, or the relationship of science with technology and society are some of these examples.

Even so, it does not seem that the school curriculum pays special attention to it. As surprising as it may seem, in the Primary Education stage these contents are found in the Social Sciences subject from the LOMCE .

Contents “in passing”

In a similar way to previous laws, the current curriculum of the Primary stage dedicates a brief space to this subject (approximately 6% of the learning standards). The contents that are worked on have not changed in recent years either. Among them we find the origin of the universe, its components, the solar system, the movements of the Earth and their consequences and, finally, the translational movement of the Moon with its phases.

In the next stage, Secondary, these contents appear again, generally in the first year in the Biology and Geology subject. After this early teaching, astronomy practically disappears from the curriculum. With this, it is not surprising that several investigations have pointed out the deficiencies of the students to understand some basic questions of astronomy.

How is astronomy taught today?

The first contact occurs at school, but does our educational system favor the interest of students in astronomy? The teachers are responsible for this work, although the truth is that little has been prepared for it.

It must be taken into account that more than 80% of future teachers who are currently studying the teacher’s degree left the learning of science at the age of 15 (3rd of current ESO). At that time they are no longer mandatory, unlike mathematics or history, for example. This is the case from LOGSE (1990) to current law.

In addition, the years of university studies that these future teachers of the Infant and Primary degrees spend focused on other specialties do not help either to fill the gaps in their training when they completed the compulsory stages.

We have, therefore, a system that has poorly trained teachers in this and other branches of science and that forces them to teach astronomy in a very compressed way in the curriculum.

In this way, the teaching of astronomy to Primary students is carried out, in most cases, in a merely bookish way, without departing from the content of textbooks, which develop this scientific field from the largest and most distant to the closer, an order contrary to observation and, consequently, to the history of astronomy.

Neither is any observation made (neither daytime, nor night), nor are its applications in human life shown, nor in the historical development of this science.

A science literacy course?

To improve the teaching of astronomy it might sound suggestive to design a complete subject in Primary, but who would teach it? Furthermore, it does not seem a good idea to add more and more subjects to a school curriculum that has courses with 12 subjects, and to which new ones are often suggested from the most disparate positions.

A solution would be to try to extend the contents of astronomy beyond 1st year of ESO, gaining in depth each year, for example, adding part of the historical development until reaching the concept of gravity in Physics and Chemistry of 2nd and 3rd year. THAT.

It would also be important to have all students take a subject that contributes to their scientific literacy. It should have a rigorous character but with an informative tone. And contain contemporary science topics in which astronomy occupies an important part.

Such a subject already existed in the previous educational law ( LOE ), Sciences for the Contemporary World, compulsory for 1st year of High School. It was replaced in the last reform (LOMCE) by Scientific Culture, this time for 4th of ESO and 1st of Baccalaureate, but of an optional nature and which, therefore, goes unnoticed by non-interested students.

Retaking the compulsory nature of a subject that contributes to achieving a scientifically informed student body, in astronomy and other subjects, would undoubtedly be an improvement for the training of our future citizens.

Author Bio: Rafael Palomar Fons is Professor of Didactics of Sciences at the International University of Valencia