Group work or “cooperative learning” is often used in education, whether in school, college, high school or university. In 2018, a survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on educational practices revealed that nearly one in two French teachers, out of 1400 people questioned, relied on work in small groups. within their class.

While they generally consider cooperation as useful, in particular for promoting empathy, critical thinking or even the motivation of students, teachers and teachers do not always experience the setting up of these experiences positively .

Social psychology has long identified the difficulties associated with working in a group, such as the phenomena of social laziness , group thinking , or even conformism .

In groups where cooperation is not structured effectively, some students may take advantage of the situation and not contribute to collective work: this is the phenomenon of social laziness. Group thinking, on the other hand, emerges when group members need to reach consensus, when time and resource constraints are important. In this case, individuals tend to conform to the majority, and the quality of the group product may be impacted.

Set common goals

Thus, unstructured group work can lead to a decrease in individual efforts. Research in education indicates that there are different ways of structuring cooperative learning in order to optimize its effectiveness and to remedy the difficulties mentioned above. Brothers David and Robert Johnson (2009) identified several elements that determine the effectiveness of cooperation.

First of all, we must establish a common goal and a situation where each member of the group is encouraged to get involved if they want to increase both individual and collective success. This “positive interdependence” generates opportunities for students to engage in group management and helping behaviors which, in turn, enhance learning.

In an educational context, the common goal may consist of a presentation, a written report or of evaluations, collective or individual. In order to reduce the effects of social laziness, researchers recommend empowering participants by forcing them to account for their work. The group as well as the members who constitute it must then be evaluated on their ability to meet the educational objectives set by the teacher.

In this article, we have chosen to focus on one of these cooperative learning methods: “the puzzle class” . The latter was created by Aronson and his colleagues in the 1970s, in order to promote the integration of ethnic minorities following the desegregation of American schools. Since its inception, over a hundred empirical articles have been published on the “puzzle class”, which enjoys significant popularity with many teachers .

Learn to explain

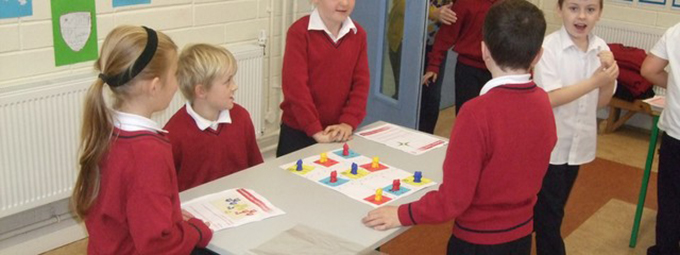

The “puzzle class” is structured to follow three main steps, described below.

“Individual” phase: Initially, each member of the groups (made up of 4 to 6 students) works individually on part of the material to be learned beforehand divided by the teacher (here 3 content represented by a different color). In our example, it could be a synthesis of information on additional themes characterizing the period such as: the great discoveries (Blue), the absolute monarchy in France (Yellow) or the French Revolution (Green).

“Expert” phase: Secondly, each of the students leaves their group to meet, as part of a new working group, the students who have the same body of information as them. They thus form a group of experts to exchange and synthesize this information. For example, group 1 will be made up of students who have worked on the sub-section “the great discoveries”.

This step of the process is particularly important because it gives less experienced students the opportunity to build on their more experienced peers in order to gain the best control over the body of information assigned to them. “Expert” groups give all students the opportunity to get a clear idea of how to present the material to their peers, regardless of previous inequalities in skills or preparation

“Puzzle” phase: Finally, the pupils return to their original groups and will present the material on which they have become “experts” to their classmates. Thus, each group has access to the entire content of the course by pooling the knowledge of the different members, like a puzzle.

To structure positive interdependence, the teacher can prepare an assessment covering all of the content or group presentations which require the articulation of the different sub-parts by the pupils. Indeed, it is important that the students integrate the information and develop a global point of view on the lesson.

To summarize, the “puzzle class” is an approach that requires rigor in the smooth running of the steps. It is therefore preferable to anticipate the creation of groups, the arrangement of the class and the preparation of the material beforehand so as not to waste time during the course.

The main difficulty lies in the ability of students to summarize and convey the main ideas of the content they are to study. Explaining and teaching is not easy. Moreover, work in educational psychology suggests training students before implementing such practices in order to maximize their effects.

Ritualize the courses?

In addition to the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, the “puzzle class” very often makes it possible to create a valuable relational fabric for students, whose beneficial effects on quality of life and university success are known. This is an important element at the university because some are in a situation of social isolation, especially during the first years of the License.

However, it should be noted that with this method, students are experts on only part of the puzzle. This limit therefore implies making sure that everyone has had the opportunity to gain an in-depth knowledge of the other parts of the puzzle. At university, this personal in-depth work can be done at home.

Likewise, the “puzzle class” can be practiced in secondary school. During interviews with middle school teachers who experimented with this method for a quarter, an involvement and increased participation of students in their classes were noted: the majority of students played the game, helped their peers, and assumed the mission of joint work, some having even adapted the distribution of resources and roles in their own work as a result of the experiment.

Interviewees nevertheless raised some limitations regarding the use of the “puzzle class” method. According to them, it requires an adaptation of the teaching practice and an important preparation to set up various activities and to distribute the pupils in the groups. Likewise, not all students participated with the same degree of commitment and enthusiasm, and communication in the groups was not easy during the first cooperative work sessions.

As such, the teachers raised the importance of the “ritualization” of their course, an important step for the objectives of the lesson and the functioning of the puzzle class to unfold effectively. Despite everything, for these teachers, the contributions of the “puzzle class” on the development of their students were substantial, and their satisfaction with the device led them to think about other ways of implementing group work. in their classes. So, ready to “dare cooperative pedagogies “?

Author Bios: Arnaud Stanczak is a PhD student in social psychology, Anais Robert is a PhD student in Social Psychology and Michael Dambrun is a Teacher-researcher all at Clermont Auvergne University (UCA)