If you are drafting, it is pretty easy to find a lot of advice about the benefits of free writing. Lots of people find that timed writing sprints help to generate content. Unstructured writing is useful to work out what you want want to say. The pomodoro sprint works really well for many academic writers, and it it used to kick off a wider variety of topics and genres. However, it is always useful for any academic writer to have a few alternative strategies in their repertoire.

If you are drafting, it is pretty easy to find a lot of advice about the benefits of free writing. Lots of people find that timed writing sprints help to generate content. Unstructured writing is useful to work out what you want want to say. The pomodoro sprint works really well for many academic writers, and it it used to kick off a wider variety of topics and genres. However, it is always useful for any academic writer to have a few alternative strategies in their repertoire.

If you are the kind of person who has a notebook, or who jots down a few random thoughts when you are starting to work on a paper, then this low key, note-based twelve step strategy might work for you – and for some of the things you need to work on. Like all writing strategies, it’s not a one size fits all approach, it s a start-small-start-with-bits-and-build-up. Here’s how it goes.

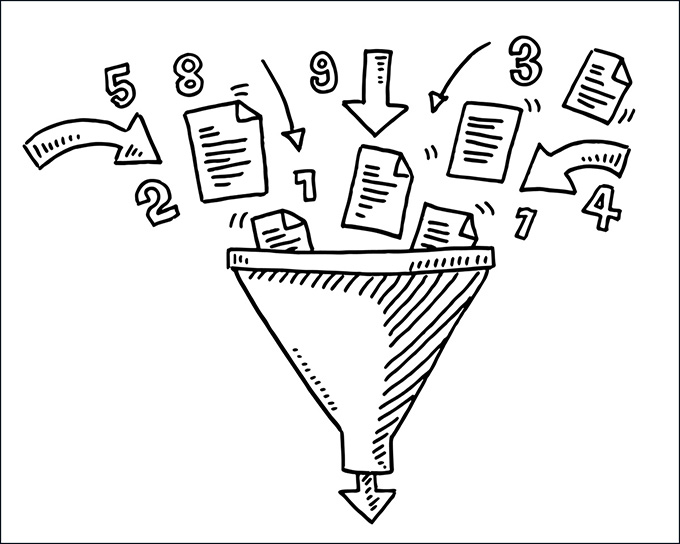

1. Compile all of your scrappy notes, reading responses, bits of worked data, questions and fragments of thoughts. Bring them together in one place. In one document. Name it – (topic) workings.

2. Make these random bits of stuff into a long list. Bullet or number them if you want.

3. Group the things that seem to go together into larger pieces. ( You might want to do this exercise using posits or on a whiteboard or by making a mind map).

4. Next, write each of the little bitty bits into larger chunks. This means moving everything into proper sentences.This means making the sentences into something that makes some sense as a stand-alone. ( We might call these paragraphs or even several paragraphs, but we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves.)

5. Shuffle these chunks around until you are satisfied that they are in some kind of order that seems relatively logical – remember these things are always a bit arbitrary and you can shuffle them around again if this ordering doesn’t work .

6. Now read through the chunks. You will see that there are bits missing. What might make the existing chunks hang together, flow more? Have a first go at writing in what could link the chunks together – make these thoughts into idea brackets, as in … [I need to talk about x here] or [perhaps the what connects these two things is y]. You might even have something at the start or in the margins like [this seems to be developing into an argument about a, b, and c]. it can be helpful to use a powerpoint here, just to assess how the order of things works out – shaping media often generates new insights as you see things differently.

7. Rest. Then read through the text that you have made. Make any changes or additions to the [ …] that you need to.

8. Turn the […] into writing, into more complete thoughts. One at a time. One sentence after another. You don’t have to do the […] all at once. (And yes, these too might turn out to be paragraphs or several paragraphs but we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves).

9. Read through the lot two or three times, then step away from the screen for a few days.

You can of course do any of these 1-8 steps as single activities or, if you have more time, they can take up larger blocks of time. It’s probably a good idea not to do them all at once because you probably need time to let the ideas just percolate. Let your subconscious keep working while you do something else. However, if you get a rush of energy and insight then just go with it and see where it goes. And of course you can do some focused free writing (pomodoros) around any of the points or […]s.

And finally,

10. Read through the text you have written, asking yourself whether you have something that resembles a drafty draft. Perhaps it still needs a big point. Perhaps it needs a stronger argument. Perhaps it needs to be more firmly directed to a particular reader. ( You may already have had a reader and a publication outlet in mind right at the start. I usually do. But if you don’t, try to get that sorted now.) And you might find that getting clear about your controlling purpose is helpful at this point. Or you might like to write a Tiny Text to get the big idea, argument and reader sorted out. after this, you may find that the text needs reordering again in light of these decisions. The text probably needs more referencing, but you can leave that to the next stage if you want.

11. Decide what needs to be added and changed. Make the changes. Make sure you add something like a bit of an introduction and conclusion if it isn’t there – remember that these have to “shake hands” and refer to each other.

12, Transfer all of this to a new doc. Name it (topic) first draft. Date.

And – Voila.

At the end of these twelve steps, you will have something that is rather like a crappy first draft. That’s because it is a crappy first draft. Victory. A text you can work on further. A text that might still need quite a bit of finessing. But a text nevertheless – a text that is now assembled, rather than remaining a randomness of scattered thoughts.