For all its faults, 2020 appears to have locked in momentum for the open access movement. But it is time to ask whether providing free access to published research is enough – and whether equitable access to not just reading but also making knowledge should be the global goal.

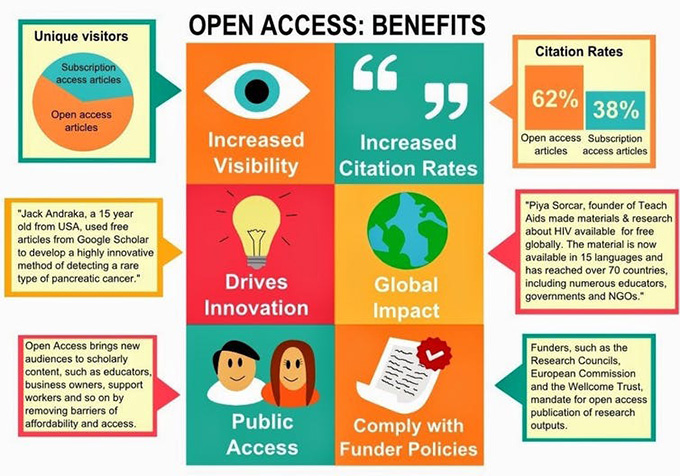

An explanation of open access and how the system of having to pay for access to published research came about.

In Australia the first challenge is to overcome the apathy about open access issues. The term “open access” has been too easy to ignore. Many consider it a low priority compared to achievements in research, obtaining grant funding, or university rankings glory.

But if you have a child with a rare disease and want access to the latest research on that condition, you get it. If you want to see new solutions to climate change identified and implemented, you get it. If you have ever searched for information and run into a paywall requiring you to pay more than your wallet holds to read a single journal article that you might not even find useful, you will get it. And if you are watching dire international headlines and want to see a rapid solution to the pandemic, you will probably get it.

Many publishing houses temporarily threw open their paywall doors during the year. Suddenly, there was free access to research papers and data for scholars researching pandemic-related issues, and also for students seeking to pursue their studies online across a range of disciplines.

Safia Begum/The Blogworm/Aston University

In October 2020, UNESCO made the case for open access to enhance research and information on COIVD-19. It also joined the World Health Organisation and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in calling for open science to be implemented at all stages of the scientific process by all member states.

There is clearly an appetite for freely available information. Since it was established earlier this year, the CORD-19 website has built up a repository of more than 280,000 articles related to COVID-19. These have attracted tens of millions of views.

Europe has led the way

Europe was already ahead of the curve on open access and 2020 has accelerated the change. Plan S is an initiative for open access launched in Europe in 2018. It requires all projects funded by the European Commission and the European Research Council to be published open access.

A 2018 report commissioned by the European Commission found the cost to Europeans of not having access to FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) research data was €10 billion ($A16.1 billion) a year.

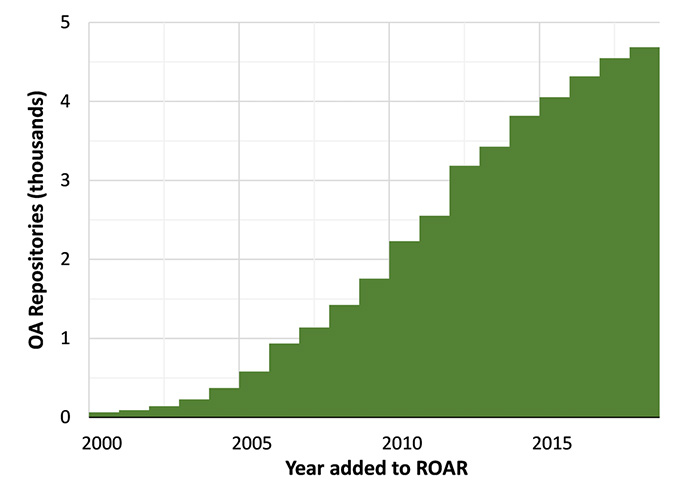

Growth in the number of open access repositories listed in the international Registry of Open Access Repositories. Thomas Shafee/Wikipedia

In 2019, open access publications accounted for 63% of publications in the UK, 61% in Sweden and 54% in France, compared to 43% of Australian publications.

Australia is lagging behind

Australia’s flagship Australian Research Council has required all research outputs to be open access since 2013. But researchers can choose not to publish open access if legal or contractual obligations require otherwise. This caveat has led to a relatively low rate of open access in Australia.

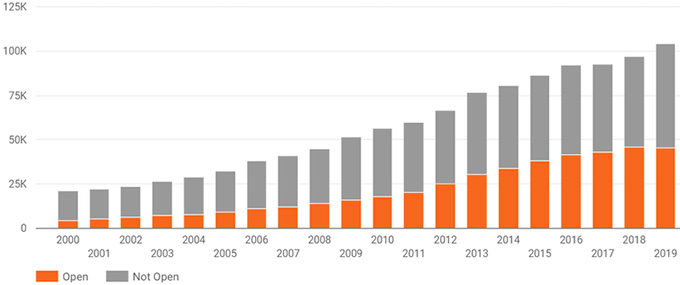

The increase in the numbers of open access publications in Australia has been gradual. Open Access Dashboard/Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI)

The Council of Australian University Librarians (CAUL) and the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (AOASG) have long carried the torch for open access in Australia. But, without levers to drive change, they have struggled to change entrenched publishing practices of Australian academics.

Our Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI) project has examined open access across the world. We have analysed open access performance of individuals, individual institutions, groups of universities and nations in recent decades. The COKI Open Access Dashboard offers a glimpse into a subset of this international data, providing insights into national open access performance.

This analysis shows a steady global shift towards open access publications.

For example, in November 2020, Springer Nature announced it would allow authors to publish open access in Nature and associated journals at a price of up to €9,500 (A$15,300) per paper from January 2021. This was a signal change for the publishing industry. One of the world’s most prestigious journals is overturning decades of closed-access tradition to throw open the doors, and committing to increasing its open access publications over time.

At the moment, the pricing of this model enables only a select group to publish open access. The publication cost is equivalent to the value of some Australian research grants. Pricing is expected to become more affordable over time.

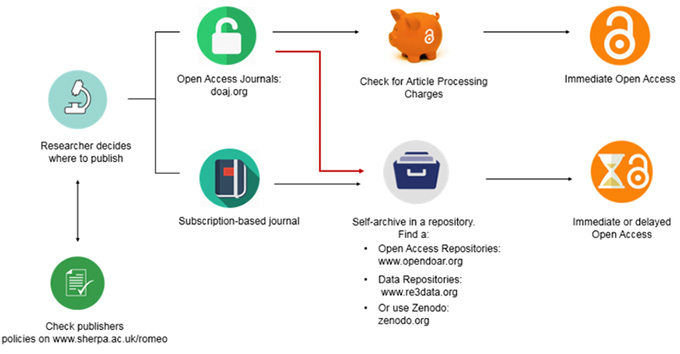

A quick guide to open access publishing: for researchers who wish to do this the required fee can be a significant deterrent. OpenAire

It’s not just about access to facts

This international trend is a positive step for fans of freely available facts. However, we should not lose sight of other potentially larger issues at play in relation to open knowledge – that is, a level playing field for access to both published research and participation in research production.

Put another way, we need to pursue not only equity among knowledge takers but also among knowledge makers if we are to enable the world’s best thinkers to collaborate on the planet’s signature challenges.

All of this is good news for people who love to access information – but the bigger overall question for the higher education sector is about the conventions, traditions and trends that determine who gets to be considered for a job in a lab or a library or a lecture theatre. There is much more to be done to make our universities open for all – a future of equity in knowledge making as well as taking.

Author Bio: Lucy Montgomery is Program Lead, Innovation in Knowledge Communication at Curtin University