Two small boxes in the department of archives and modern manuscripts at Cambridge University Library contain a few pieces of detritus from an extraordinary afternoon in Cambridge in 1897.

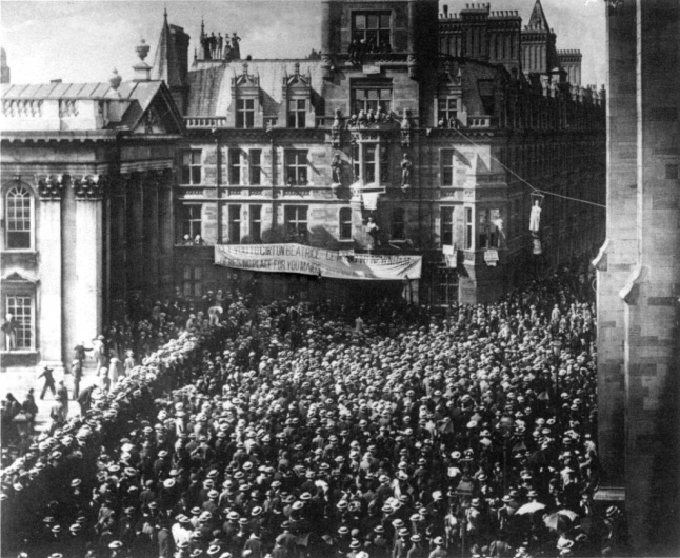

That day, crowds of undergraduates gathered to protest against a change in ordinances that would allow women to be granted degrees and membership of the university. They threw confetti from upper windows, let off rockets and crackers, and hurled eggs at those eligible to vote. Someone – we don’t know who, sadly – recognised the significance of the day and thought to collect some of the fallen confetti, eggshells and spent rockets.

Twenty-four years later, this quirky collection was deposited in the department of manuscripts at the university library by Arthur Sidney Banting Miller, a member of staff. The description on the box explained in a tone of gentle irony that they were “the arguments” used against granting degrees to women.

Female students had been permitted to attend lectures at Cambridge from 1869 and to sit exams from 1881.However, the reward for their efforts was a certificate of attainment from their college. They could not claim to hold a degree or put BA after their name

Even Philippa Fawcett, who performed better than the senior wrangler (the highest-placed male student in the maths final examination) in 1890, did not have her intellectual achievement acknowledged in the same way. Numbers were increasing at the two women’s colleges, Girton and Newnham, during this period, reflecting the growing demand among women to take advantage of higher education. At that time, most women were still taught at home and did not share the standardised general education provided for boys who were sent to school. They often relied on ad-hoc tutoring or governesses who were themselves not the beneficiaries of a formal education.

In 1897, there were two issues under discussion. The first was that women should have their hard work and achievements acknowledged by the awarding of a degree. The second was that they should be given full membership of the university with all the rights and privileges that that entailed.

Many of the comments recorded in reports and letters to the press express anxiety that if the first issue was allowed, the second would follow. While there must have been a myriad of different views and opinions among the opponents, what comes through most consistently – and I’m reading between the lines – is the fear that women might have a say in the future development of the university by being members and having a vote in the decision-making process.

There are comments that Cambridge was founded as a men’s university and should remain a men’s university.Some commenters referred to a “womanly education” and the fear that men’s classical education would be undermined by the loss of compulsory Latin and Greek. Nationally, there were greater opportunities for women in higher education. London University had granted degrees to women from 1878, with Wales, Durham and the Scottish universities following in the 1890s.

The protesters at the 1897 vote were no doubt delighted when the Senate voted by 1713 to 662 against the motion. Newspaper articles record that a number of them marched over to Newnham and continued their protest outside the gates.

It was not until 1921 that any progress was made for the female students. In another vote, they were finally given the title of the degree of bachelor of arts, but were still not to be members of the university. Despite female lecturers being appointed from 1926, and Dorothy Garrod becoming the first female professor in 1939, full membership was not given until 1948.

Philippa Fawcett died in June 1948 – she lived long enough to know that women were finally being given equal rights in Cambridge.

At the university library, we have been overwhelmed by the reaction to these simple items that were an entry into our internal digitisation competition. Colleagues and people from all over the world have expressed surprise, indignation and heartfelt outrage at the attitude that so many members of the university and undergraduates showed to these women in 1897.

The response has made us even more determined to ensure that this story is not forgotten and is available to as wide and as broad an audience as possible.

The rockets and confetti will be digitised over the coming weeks, using innovative technology to include 3D imaging. We hope that it will form part of a virtual collection in our digital library of women’s contributions to the university that perhaps are not widely known.

In this year of celebrating the centenary of some women getting the vote, it’s important to remember another parallel fight for equality. I’m looking forward to delving deeper so that we can present the story in a way that does these hard-working and pioneering women justice.

Author Bio: Sian Collins is an archivist at Cambridge University library.