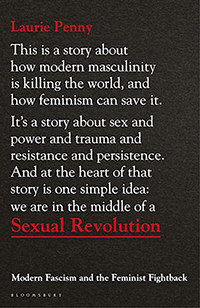

The world”, declares Laurie Penny on the first page of their new book, “is in the middle of a sexual revolution.” And unlike earlier sexual revolutions, this one is for real – provided we eradicate capitalism, fascism and the patriarchy.

With this call, it’s business as usual for British writer and activist Penny, who has never sugar-coated their feminist and radical politics.

Penny – who is genderqueer and uses they/them pronouns – first came to public attention in the 2000s with the blog Penny Red and regular columns in left-leaning outlets like the Guardian and New Statesmen. A steady stream of books followed, with arresting titles like Unspeakable Things (2014) and Bitch Doctrine (2017), in which Penny dared to call out the sexism of the radical-left circles in which they moved.

Anticipating the first-person feminism of Australia’s Clementine Ford, among others – and updating the 1970s mantra ‘the personal is political’ for a new generation – Penny has often shared difficult and intimate personal experiences, from anorexia to masturbation to sexual assault. And while they have been what would now be described as “extremely online”, they have also gone in person to where the action is, whether taking part in the Occupy movement or travelling to Greece to observe the financial crisis up close.

Anticipating the first-person feminism of Australia’s Clementine Ford, among others – and updating the 1970s mantra ‘the personal is political’ for a new generation – Penny has often shared difficult and intimate personal experiences, from anorexia to masturbation to sexual assault. And while they have been what would now be described as “extremely online”, they have also gone in person to where the action is, whether taking part in the Occupy movement or travelling to Greece to observe the financial crisis up close.

Given all that Penny has been writing and protesting about for well over a decade, it was inevitable that they would write what could broadly be described as a #MeToo book – indeed, most of their six previous books have been #MeToo books of a kind. Penny deserves recognition for writing about sex and power in unapologetically feminist terms when mainstream feminism was widely considered to be in the doldrums, passé, and/or no longer necessary.

Still, it’s no longer 2007 – which, as well as being the year Penny started blogging, was also the year that African American activist and survivor Tarana Burke launched the #MeToo movement, her hashtag raising awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual harassment and assault.

Since 2017, when #MeToo went viral and then global, countless words have been written about it by feminists, including Burke, whose memoir Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement (2021) is essential reading. Penny is entering a crowded field, inviting the question of what is new and distinctive about the grandiosely titled Sexual Revolution: Modern Fascism and the Feminist Fightback.

Tanara Burke launched the #MeToo movement in 2007. Mick Tsikas/AAP

At their best, Penny offers a rousing and enticing prediction for what sits on the other side of the #MeToo era. For Penny, the present moment is one in which “sex and gender are in crisis”. #MeToo is part of a “Great Reckoning” that almost nobody saw coming, because “when it came, it came from women”.

We are now “living through a profound and permanent alteration in what gender means, what sex means, and whose bodies matter”.

Everywhere “women, men and LGBTQ people … are walking quietly away from the expectations posed on them by thousands of years of patriarchy”. The changes underway promise “ways of life that are not based on competition, coercion and dominance but on consent, community and pleasure”.

Yet rather than telling us more about the “paradigm shift” that is remaking “our civilisation”, Penny’s book mostly explains the present moment by covering similar terrain to their earlier titles, with some new piecemeal research and updated terminology.

Frequently, Penny’s declarative mode undercuts rather than generates analysis. The abrupt pivots throughout suggest a book written in some haste. Anecdotal evidence and personal experience drive the narrative and analysis, so much so that Penny’s own journalism is alluded to rather than showcased.

For instance, Penny tells the reader that they have spent years “researching and attempting to understand the mindset behind the incel and ‘men’s rights’ and ‘seduction’ communities” and that the “problem is getting worse”. But rather than properly extrapolate, Penny references a few random studies and concludes with an ode to the heroes of the global pandemic – “not fighters or soldiers”, but “doctors, nurses, care workers and community leaders”.

The flashpoints of sexual and gender politics

There’s no doubting Penny’s ambition. Across 14 chapters, most with an arresting if formulaic opening (“Pain is political, and so is pleasure”; “Heterosexuality is in trouble”; “Sooner or later, every revolution comes down to who does the dishes”), Penny covers the flashpoints of contemporary sexual and gender politics, including #MeToo and the backlash against it.

Much of what is argued is easy to agree with: capitalism exploits some people and bodies more than others; women continue to carry the weight of domestic and caring labour; economic and sexual exploitation are not separate issues, but are intimately linked.

In the chapter focussed on work, Penny refreshingly moves #MeToo beyond the realm of celebrity to other industries, such as hospitality, agriculture and domestic work. They devote the most attention to sex work as paradigmatic of all labour under capitalism. Yet Penny cuts short rather than enhances another promising thread by focusing on arguments that have been made more powerfully by others. These include sex workers themselves, as showcased in the anthology We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival (2021).

The organising themes of sexual revolution, modern fascism and feminist fightback provide some cohesion, but not in an especially sustained or persuasive fashion.

In Penny’s telling, “modern fascism” is a catch-all term that includes “neo-masculinist” strongmen like Putin, Bolsonaro, Trump and Johnson, the “overwhelmingly White men” who voted for them (a claim in need of some qualifications), incels, the far right, and any man experiencing a crisis or threat to his masculinity. It is a “brutal political backlash” provoked by “changes in the balance of power between men and women”.

Now, it is clear that authoritarian governments everywhere are much more likely to take away women’s rights than extend them, as Penny covers in a chapter on reproduction that focuses mostly on the US. But to make the case that “modern fascism” is best understood as a backlash against feminism requires more work than Penny is willing to do.

Other feminist thinkers have offered far more probing and genuinely disturbing accounts of contemporary misogyny, including another British journalist Laura Bates, in her book Men Who Hate Women: From Incels to Pick-up Artists (2020)

The genealogies of #MeToo

Like “modern fascism”, the “feminist fightback” is taken as a given, rather than something to be accounted for or documented. Penny prefers sweeping statements about “the greatest challenge to the social order in this century” coming from

women, girls and queer people, particularly women, girls and queer people of colour, finally coming together to talk about sexual violence and structural abuse of power.

Furthermore, the “feminism” most often referenced is not the left, black or trans feminisms Penny seems most aligned with. It is the “choice”, neoliberal, mainstream feminism she criticises (as have many other feminists in far more encompassing fashion). For a self-proclaimed feminist book, Sexual Revolution is sparsely populated with actual feminists and largely bereft of feminist history. It is as though #MeToo came from nowhere.

Genealogies have been identified and scrutinised by Tania Serisier in her important book Speaking Out: Feminism, Rape and Sexual Politics (2018), among many others, including Tarana Burke. Yet in place of proper details about “feminist fightback”, we get Penny’s intervention: sexual revolution.

Cognisant that the concept of “sexual revolution” comes with hefty historical and cultural baggage (though not to the extent that they engage with relevant critiques), Penny attempts to rehabilitate it anyway. This sexual revolution, writes Penny, will deal “not just with sexual licence but with sexual liberation” – as though they are the first rather than umpteenth person to make this argument. This “new sexual revolution is a feminist one”.

The idea of sexual revolution as unfinished business is decades old. So are expressions of what a “feminist” sexual revolution might entail. Penny’s update is to advocate for consent as the fundamental basis of the new sexual and economic order. Of course! But if we are at the midpoint of a sexual revolution, as Penny suggests, there is very little sense of positive developments in the sexual sphere.

The idea of sexual revolution as unfinished business is decades old. So are expressions of what a “feminist” sexual revolution might entail. Penny’s update is to advocate for consent as the fundamental basis of the new sexual and economic order. Of course! But if we are at the midpoint of a sexual revolution, as Penny suggests, there is very little sense of positive developments in the sexual sphere.

Instead, Penny’s focus is overwhelmingly on how dire heterosexual relations are and how abhorrent the sexually desiring woman continues to be.

Sexual Revolution is a bulldozer of a book in which Penny opts for full-throttled polemic instead of nuanced analysis at almost every turn. There has always been a place for such books in the feminist canon, and Penny brings flair and spirit to the task. But beyond its potential value as a primer for contemporary feminism, it is difficult to discern who Sexual Revolution is written for.

I suspect most readers are already familiar with “patriarchy”, “rape culture”, “toxic masculinity”, “intersectionality”, and other key terms.

From the rote to the muddled

Though Penny was once a welcome feminist voice at a time of “post-feminism”, Sexual Revolution reads as outdated, or not up to its proclaimed task, despite its contemporary focus. It suffers from comparison with other books which have tackled similar material with more depth and insight.

The major titles of the #MeToo era have involved forensic investigative reporting. She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Started a Movement by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, and Catch and Kill by Ronan Farrow, both released in 2019, focussed on the case of film producer Harvey Weinstein and the women he targeted.

Penny promises a more wide-ranging and grassroots approach to sex and power, but only really skims the surface. In contrast to the polyphonic format of numerous anthologies, including the edited collection #MeToo: Stories from the Australian Movement (2019), Penny’s voice eclipses the voices of people she knows have often been marginalised, including Indigenous women, women of colour, and trans, queer and non-binary people.

Penny is attentive to the racial and racist dynamics of both the far right and mainstream (or White or carceral) feminism. But these discussions are too condensed to take root and sometimes read as rote. “Quite apart from being ethnically suspect,” Penny states, “any movement to end exploitation that fails to centre race is intellectually useless.”

In terms of connecting the dots between White feminism and political Whiteness, a more illuminating book is Alison Phipps’ Me Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism (2020). Phipps carefully and powerfully draws out the racist logic of what has come to be known as “carceral feminism” – an approach that advocates for increased policing, prosecution and imprisonment as key strategies for combating violence against women – evident in some parts of the #MeToo movement.

Penny’s book is muddled by comparison in the solutions it offers for dealing with perpetrators of sexual violence. As for the victims, Penny is sensitive to how and why they are often dismissed as “mad” or unreliable, but Sara Ahmed’s recent book Complaint! (2021) takes the subject much further and in new directions.

Proper comprehension of what consent entails is at the heart of Penny’s sexual revolution. Given that it was only last year that NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller thought a consent phone app was a good idea, Penny’s promotion of “real, continuous, enthusiastic sexual consent” is welcome.

Yet as Kathleen Angel persuasively argues in Tomorrow Sex Will be Good Again: Women and Desire in the Age of Consent (2021), the contemporary fixation on consent as the solution to the pervasive problem of sexual violence can place additional burdens on women, including the need to know emphatically what they want sexually.

In making this argument, Angel hardly disavows the “bare minimum” of consent as central to contemporary sexual ethics. But she’s also sceptical about the very notion of “sexual revolution” that Penny so heartily advocates. Her book’s title is a reference to philosopher Michel Foucault’s highly influential critique of what he saw as one of the delusions of the earlier so-called sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s – that tomorrow sex will be good again.

As Penny recognises, #MeToo is not a stand-alone event or movement, but an expression of wider social patterns. It is a tipping point in understanding the ubiquity of sexual and gendered violence. It has galvanised feminism, and redirected and refocused contemporary discourses around gender and sex.

But its effects are too varied, diffuse and contradictory for the sledgehammer treatment Penny favours. Other feminist thinkers, such as British academics Amia Srinivasan and Jacqueline Rose, have pursued far more generative approaches. Srinivasan has productively revisted the feminist “sex wars” in The Right To Sex (2021), while Rose has consistently turned to psychoanalysis, most recently in On Violence and Violence Against Women (2021).

A reckoning

Penny is more successful in capturing the affective dimensions of the #MeToo era. On this front, Sexual Revolution is a worthy successor or companion to Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger (2018) and Rebecca Traister’s Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger (2018), two early responses to #MeToo and the Trump presidency. These books are clearly part of the same zeitgeist, as their almost identical subtitles indicate.

While Penny clearly shares their faith in the political potential of rage (not all feminists do), Sexual Revolution is more useful is in its reflections, right at the end of the book in an extended endnote, on “trauma politics”.

Penny writes that “pain is not supposed to be part of the political conversation”. But it has become so, and the connections or continuities between intimate and structural forms of violence have become much more explicit.

Where Penny leaves us is where Australian journalist Amy Remeikis begins in On Reckoning (2022), her recently released and already bestselling monograph: the moment at which the complicity of modern politics in gendered violence is made starkly and painfully apparent.

For Remeikis, this was the day after former parliamentary staffer Brittany Higgins went public on 15 February 2021 with the allegation that she had been raped by a male colleague in Parliament House in March 2019. Some 24 hours later, Prime Minister Scott Morrison addressed the nation. At the prompting of his wife Jenny, Morrison declared that “he’d been reminded to think of the situation as a father”.

A parliamentary reporter, Remeikis was at work, typing out the Prime Minister’s words. She was first traumatised, then enraged by them: “Somebody else’s daughter. We always have to be somebody else’s daughter.”

Soon after, Remeikis shared her own experience of sexual violence in the Guardian, becoming a spokesperson for survivors in the process. On Reckoning powerfully reiterates and extends her key point that being “thought of as someone else’s daughter is not empathy”. It obliterates the experiences of real, rather than imagined victims. It sets limits on whose pain can even be conceived. Is it any wonder then, writes Remeikis, that “First Nations women, women of colour, trans and culturally and religiously diverse women have found it so hard to be heard?”

In the #MeToo era, the word “reckoning” has been used so often it can slip into meaninglessness. But Remiekis – like another Australian journalist Jess Hill, in another recently released essay with an almost identical title The Reckoning: How #MeToo is Changing Australia (2021) – imbues it with fresh force.

As records of Australia at a moment of profound cultural change, they offer vital local and personal perspectives of a global phenomenon that has – among its many effects – reinvigorated feminist writing for the mainstream, mostly for the better.

Author Bio:Zora Simic is a Senior Lecturer, School of Humanities at UNSW Sydney