It’s frightening to imagine where the world would be right now without mRNA vaccines. The COVID-busting technology revolutionised vaccine development at an internationally critical moment – with massive implications for people’s health, wellbeing and the global economy.

Yet imagine we must – because some of the research most crucial to the development of mRNA vaccines almost didn’t happen.

Biochemist Katalin Karikó’s fascination with the therapeutic potential of mRNA began in the early 1990s, but she received little encouragement. She was undervalued and underfunded throughout her university career and eventually left academia.

When she went on to jointly win the Nobel Prize for Medicine for her pioneering role in developing the mRNA technology that allowed the world to take on COVID, Karikó’s former employer, the University of Pennsylvania, tried to take credit.

Yet during her time there, the university sidelined and demoted Karikó, eventually pushing her out altogether. While it would be nice to think of Karikó’s experience as an aberration, her experience – as we highlight in our new paper – is all too common for women in academia.

Barriers to women’s success

Academia is widely viewed as a meritocracy, a bastion of liberalism, and a place where people go to pursue a higher calling. The data, however, point to a dark side to the ivory tower.

For instance, a major report published in 2019 by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine showed rates of sexual harassment in academia are second only to those in the military.

More common than overtly sexualised harassment, however, is gender bias. Studies reveal women’s research receives tougher assessment, less funding, fewer prizes, and less citation than men’s. Women professors receive lower evaluations and more criticism from students – both male and female – and face higher expectations as mentors.

Women often face chilly academic climates, isolation, job insecurity, stalled promotions and unequal or limited access to resources. These tendencies can easily verge on incivility, ostracism, online abuse, academic sabotage and malicious allegations. And these problems are worse for women of colour, and those who belong to sexual and gender minority groups.

When women are brave enough to speak out, it usually backfires. At best, they may face minimisation or silencing. More damaging is retaliation, including from institutions themselves. Women can find themselves placed on probation, under investigation, targeted for character assassination, facing retaliatory accusations, demoted or even fired.

Bad for science and a waste of funding

A massive study of almost a quarter of a million US academics showed women are leaving academia at significantly higher rates than men.

They are also leaving for different reasons. While men are more likely to leave because they have been attracted by better opportunities, the number-one reason women cite for leaving is toxic workplaces.

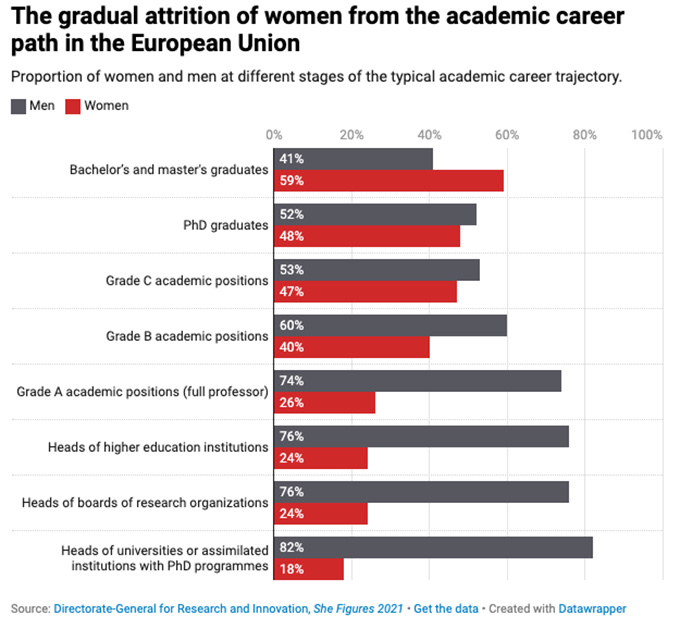

The outcome of this gradual attrition is that women continue to be vastly underrepresented in senior academic positions: as full professors, research directors, and heads of research institutions and universities.

The loss of so many women from research and higher education isn’t just a social or ethical issue. It’s also an economic one. Women in academia reflect investment. Their many years of post-secondary education, their training, their research – it all costs money. This money is wasted when they are pushed out of academia.

The worst bias and explicit harassment often comes as women achieve greater success. Rates of departure between men and women really start to widen about 15 years after academics finish their PhDs.

This means higher education and research are often losing women with the most experience and promise, and in whom the greatest funding investments have been made.

Follow the money

As current and former institutional heads and research leaders, we suggest it’s time to follow the money. Where does all this wasted money come from?

You, the taxpayer.

Higher education, research and science all are, in many parts of the world, funded mostly through public sources. This means when higher education and research organisations fail to tackle the persistent sexism, discrimination and harassment that’s driving women out, they are throwing your money out the window.

Or you can think of it another way: your taxes are subsidising sexism.

The buck stops here

The fact that tax money supports higher education and research also presents an opportunity: taxpayers can demand change in how their taxes are used.

They can demand efficiency in public funding – efficiency that will lead to less sexism in the institutions educating our children, and to more of the science we desperately need to address the collective challenges we face.

We call on governments to address sexism in higher education and research as a matter of urgency, such as by:

- acknowledging that self-regulation isn’t working.Universities and research institutions have implemented gender equity initiatives and policies for decades. Yet gender biases remain entrenched.

- developing effective and transparent systems for measuring gender equity, and applying them to all publicly funded higher education and research institutions.This means collecting and publishing data on recruitment, appointment, salaries, workload allocation, promotions, discrimination, harassment, misconduct, demotion, dismissal and departure.

- making funding in higher education and research dependent on the achievement of gender equity targets.Institutions currently receive public funding regardless of whether they uphold a fair academic culture that provides equal opportunity for men and woman.

Disregard for rules, procedures and laws designed to achieve gender equity does not hold institutions back from receiving continued public funding. This lack of accountability helps perpetuate gender bias. It needs to change.

You can join us in pressing for these changes by contacting your local representative, organising and submitting petitions, or reporting concerns to organisations designed to investigate possible abuses of public funding (such as federal auditing offices).

The story of Karikó and the transformative research that almost never was should be the wake-up call we need to demand better.

Author Bios: Nicole Boivin is Professor at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, Janet G. Hering is Director Emerita at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Susanne Täuber is an Affiliated Researcher at the University of Amsterdam and Ursula Keller works at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich