The auditorium buzzes with anticipation. It is opening night for a group of students from the Theatre for Social Change course offered at University of Waterloo.

Students are about to present the culmination of their work from the fall term. As the lights dim, the students’ fear and apprehension is palpable. Acting and performance are foreign to most of them and they are unsure of the public reception of what they about to present.

Not only are they showcasing taboo topics such as racism, inter-racial relationships, abortion and wanting to raise a baby with Down Syndrome, these actors will be subject to something most actors don’t deal with — the direct interventions of the audience members.

They are acting in theatre of the oppressed, a genre of performance developed by Augusto Boal during 1950s and 1960s in Brazil.

Oppression and education?

These students are in fact developing a set of relevant and practical tools to manage problems that they can draw upon as they move through life to foster more profound and engaging experiential encounters, while opening themselves and others to new and diverse perspectives.

My own relationship with Boal’s form of interactive theatre began 12 years ago and has since become a major focus of my research and teaching methods.

I immigrated to Canada from Iraq in 2007 to pursue a PhD in Theatre Studies at York University. There I encountered Paulo Freire’s ground-breaking book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

It was, in fact, the first book I read in Canada, and it had a massive impact on my views and considerations. It opened me up to a multitude of possibilities for creating sustainable change in how we address issues both in academia and in broader communities and I began to explore changing the learning environment in Iraq.

I began to ask myself: Might it be possible to change the relational dance between students and teachers?

Having been educated in very formal Iraqi educational institutions, Freire’s analysis of oppression and education resonated deeply with me: for him oppression is an educational process that is performed and replicated throughout society that kills creativity and engagement and instills passivity enabling complicity with dominant ways of relating.

His contentions bore a striking resemblance to what I experienced as a student in Iraq.

Students are not listening objects

In “banking education,” as defined by Freire, the relationship between the teacher and the student is an oppressive one; the teacher is the narrating subject and the giver of knowledge, and the student is the patient listening object, a merely passive recipient.

Freire describes this education as one where “the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize and repeat.”

However, Freire proposes a different education, one he calls “problem-posing,” which encourages dialogue, communication and critical thinking.

Freire remains an inspiring figure who was fundamental to theoretical development in this field. But it was not until encountering Augusto Boal, Brazilian director and activist, that I discovered the practical application of theatre to teaching.

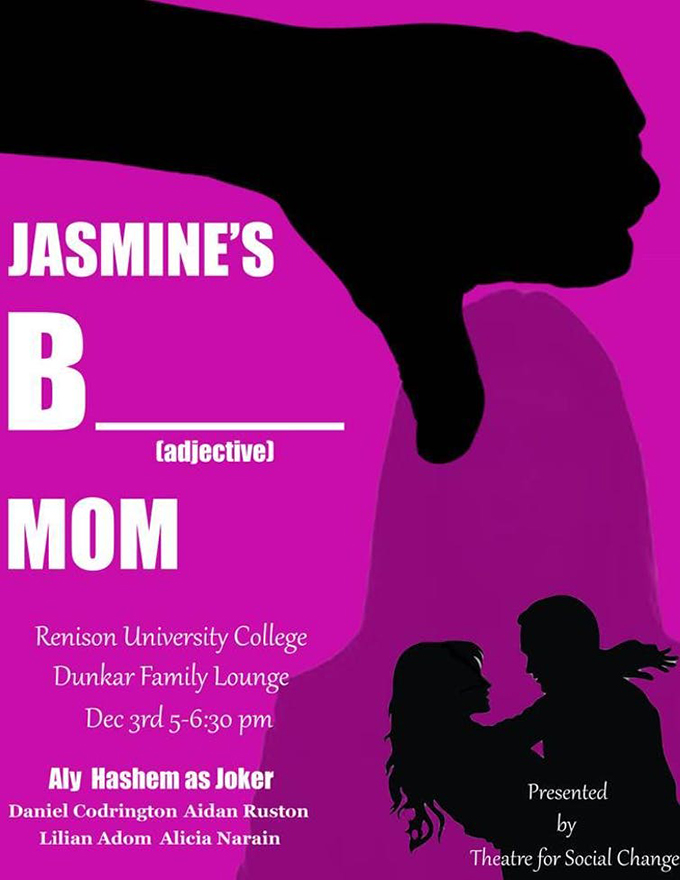

Poster from the Theatre for Social Change performance. Author provided

Boal was strongly influenced by Freire’s work: His book Theatre of the Oppressed pays homage to Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

Boal is an advocate of Freire’s view that whoever teaches learns through teaching, and whoever learns teaches in that act. Hinging on Freire’s criticism of students’ passivity and his proposed model of education, Boal endeavoured to transform the audience’s passivity in the conventional theatre into active participation.

For Boal, audience members have a dual role as “spect-actors:” spectators and actors simultaneously.

Actors perform a problem three times

Unlike conventional theatre where the audience has neither agency nor a role in what happens on stage, theatre of the oppressed provides a democratic platform where the audience is no longer simply a passive recipient of the action.

First, the spect-actors see a performance of the original script, which shows a problem or an issue.

Second, the actors repeat the show, during which the audience is encouraged to participate in the performance, with the aim of changing the outcome of the story by stopping the performance and taking the place of one of the actors onstage (usually the protagonist), or by making suggestions to the protagonist.

Third, the performers make changes to the script according to the interventions made by the spect-actors. The actors perform the amended version of the script, enabling the spect-actors to experience the results of their participation.

In each of these three performances, the audiences is guided by a trained facilitator called the “joker.”

Theatre for social justice

When I taught Theatre for Social Change for the first time this year, students began by reading about political, social and personal types of oppression.

Students then used a theatre exercise from Boal’s book Rainbow of Desire called “cop in the head” where they begin to dramatize and illustrate what their internalized oppression feels and looks like by creating a “body image sculpture.” In this human body sculpture made up of co-operating and supportive peers, a student concretely sees and dramatizes her or his experience of oppression.

Throughout the course, students were working on their final project, a piece that was collaboratively researched, written and rehearsed then performed.

Based on their research, they identified two issues: parental experiences of racism and related judgment of a youth’s white boyfriend and abortion of a baby with Down Syndrome.

The first scenario shows a Black girl introducing her white boyfriend to her mother who, triggered by her past racist experience, rejects the white boy.

The second scenario portrays a divorced, pregnant woman whose baby has Down Syndrome. She is forced by her father, on whom she depends and lives, to abort the child simply because the baby will be disabled and thus will require care and expenses that both can’t afford.

The big night

Tentative and a little shy at first, the two student “jokers” facilitating the audience interaction are visibly nervous and uncertain in such unfamiliar roles.

However, as the “jokers” warm the audience up, anxiety is forgotten, and the students project an aura of assured confidence as they lead dialogue and intervention around the tough topics featured in tonight’s performance.

Such complex and contentious issues provoke emotional and critical responses from all as they collectively unravel opposing points of view and rediscover the nuance and intricacy of human beings who exist and survive under oppressive conditions.

After the curtain, relief and applause, the students are beaming with a sense of pride and accomplishment. Mutual goodwill and optimism pervade the room hinting at the possibility of further opportunities for compelling, interactive dialogue in other forums.

Author Bio: Amir Al-Azraki is Assistant Professor, Renison University College at the University of Waterloo