Changes in the higher education sector have created the perfect environment for students to cheat – and get away with it.

New research shows that can students cheat on virtually any type of assessment.

So why is this the case, and can anything be done to prevent cheating?

Why is it so easy for students to cheat?

A nation-wide research project funded by the Australian government’s now defunct Office for Learning and Teaching, investigated the phenomenon known as contract cheating.

Contract cheating is where students arrange for an assessment to be completed by a third party. This can be an acquaintance or commercial provider.

While cheating is not a new problem, what is new is the increase of online, commercial cheating sites that target naïve or vulnerable students.

This trend is emerging in the context of increasing competition, commercialisation, corruption, cost-cutting, casualisation and credentialism in higher education.

This creates a “perfect storm” that increasingly positions learning as a transaction. Contract cheating can therefore be seen as a symptom of a strained system.

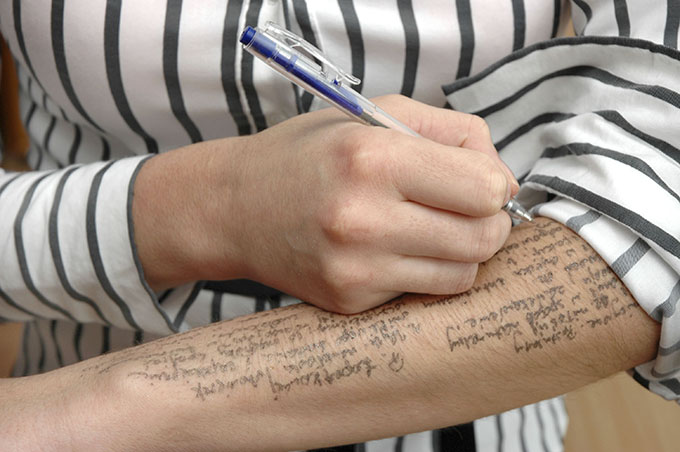

15,000 survey responses from students at 12 higher education providers found that 6% of students report using one or more of the five cheating behaviours investigated. These included:

- Obtaining a completed assignment with the intention of submitting it as their own work

- Providing assistance in an exam

- Receiving assistance in an exam

- Completing an exam for another student

- Outsourcing an exam to another student.

International students, those who speak a language other than English (LOTE), and engineering students were over-represented in the cheating group.

Students actually rarely use professional services to cheat. They are more likely to get assistance from those they know – fellow students, friends and family.

Why do students cheat?

Despite media reports claiming otherwise, students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds did not affect their views about the wrongness of cheating.

More importantly, students in the cheating group expressed significantly lower levels of satisfaction with three key aspects of the teaching and learning environment:

- Staff ensure that students understand assignment requirements

- Staff provide sufficient assessment feedback

- Staff can be approached for assistance when needed.

What can we do about it?

Unlike other components of teaching and learning (such as course/assessment design, academic integrity education, grading processes), these three items form an individualised and personal relationship between the teacher and student.

Without this, some students may be more tempted to cheat.

To foster such a relationship, teachers should be available to students for learning help and support. They need to clarify assessment requirements through succinct task instructions, scaffolding, interactive discussion and rubrics.

Teachers should also provide constructive, meaningful and timely feedback for each student. The particular needs of International and LOTE students should also be recognised.

This kind of student-teacher relationship is important when it comes to detecting contract cheating.

Data from 1,200 responses to the staff survey indicated that the most common signal to suspect an outsourced assignment is teachers’ knowledge of their student’s academic or language ability. Other tools such as text-matching software remain useful, but are secondary.

Regardless of the method used, very few cases are actually detected. And even when they are, the penalties are generally very lenient.

The most common outcome for outsourced assignments was a warning or counselling, and only 3% of cases resulted in suspension.

Around one third of the time staff are not informed of academic integrity investigations. This may make them less likely to refer future cheating cases.

Assessment design is not the solution to cheating

Survey responses and other data investigated by the project provide an evidence base to debunk the myth that assessment design will solve the problem of contract cheating.

Analysis of students’ orders on commercial cheat sites demonstrated that they are willing to outsource every type of assessment. This includes traditional essays through to reflections, practicums and dissertations.

Analysis of detected contract cheating incidents at two universities also confirmed that no assignment type is immune.

While contract cheating cannot be “designed out” of a course, this does not excuse teachers from thinking carefully about assessment design.

The focus should be on designing assessment that makes the best of learning, rather than reduces the risk of contract cheating.

As previous commentators have noted, assessment remains just one aspect of a multi-pronged and holistic approach to strengthen academic integrity.

Teachers have a responsibility to establish personalised teaching and learning relationships, and carefully design assessments. However, all higher education providers need to ensure that there are appropriate and consistently implemented processes of detection, reporting, and communication of outcomes to both staff and students.

Author Bios: Tracey Bretag is an Associate Professor; Director: Academic Integrity and Rowena Harper is Associate Director: Curriculum Development and Support, Teaching Innovation Unit at the University of South Australia