The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has released a report highlighting the many challenges of the growing presence of technology in education.

This report is groundbreaking in its call for corporate responsibility for education technology and in its recognition for the need for enhanced literacy curriculum.

In a chapter on governance and regulation, the report notes “privacy is routinely violated for private benefit,” “safety risks cannot be dismissed,” “cyberbullying is a growing concern,” “physical and mental well-being are at risk from excessive technology use” and that, globally, “almost one in four countries have introduced [cellphone bans in laws or policies].”

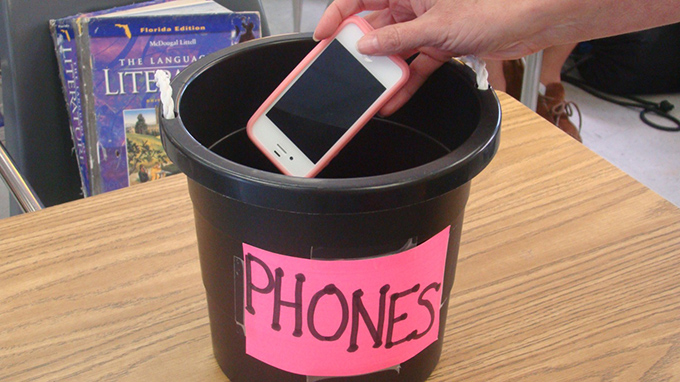

What “ban” means may vary: In 2019, Ontario introduced restrictions (sometimes called a “ban”) on using cellphones or personal mobile devices during instructional time. Devices can be used in classrooms “for educational purposes only as directed by the educator in the classroom.” CBC reported in June 2023 Ontario is the only province in Canada with an active ban on cellphones in the classroom.

Despite UNESCO’s many nuanced recommendations, some media are simply reporting UNESCO is calling for a ban on smartphones in schools. As such, there is a risk that governments will seek the simplest and least effective solution to ban cellphones in schools as a singular, one-size-fits-all approach.

This would be a mistake, since it would fail to acknowledge the complexity of youth online life and ignore the report’s most pressing recommendations for tech regulation and attention to equity. It would also fail to address the need for teaching that helps young people become more literate and make sense of a complex information environment.

Looking at youth online life

Young people gain benefits and experience challenges from their online lives. In my research, I have interviewed students who talk freely about the positive and negative outcomes of their social media use.

The U.S. Surgeon General’s recent Advisory on Social Media and Youth Mental Health acknowledged many young people find communities of affinity online and forge connections to new interests that are not available to them geographically. They explore new ways of expressing themselves.

The advisory also noted “while social media may have benefits … there are ample indicators that social media can also have a profound risk of harm to the mental health and well-being of children and adolescents.” Pervasive and unregulated social media use can lead to addictions, facilitate exploitation and radicalization and entrench mental health challenges.

Banning cellphones in schools does little as a standalone solution to such a complex relationship between youth online life and education. The solutions proposed to address such problems must not ignore how youth engage with these spaces outside the school and how pervasive online life is for youth identity formation.

Downloading responsibilities to schools

The most important finding in both the UNESCO report and U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on social media is that technology companies bear the weight of consumer responsibility, and governments must play a role in regulating these companies.

In today’s neoliberal capitalist environment — where states have shifted to become promoters of markets, and where all aspects of our public and personal lives are influenced by the economy — companies are often permitted to pursue profit for shareholders while “responsible” use is downloaded to individuals or local governments.

If some social media companies have been permitted to take advantage of the youth market for profit, then framing schools as ultimately responsible for technology use simply obscures the heart of the issue.

As the UNESCO report authors note, “The commercial sphere and the commons pull in different directions. The growing influence of the education technology industry on education policy at the national and international levels is a cause for concern.”

Our societies must advocate for governments to act in regulating technology companies. This includes enacting and enforcing age limits for social media apps, curtailing access to children’s data and curbing technology companies’ presence as the education technology industry in schools.

Implications for teaching and learning

The most relevant takeaway for public education in the UNESCO report is not that cellphones should be banned in schools. Instead, I highlight three messages as particularly useful and urgent:

1. Online learning cannot replicate or replace the merits of being together in classrooms in person.

The report acknowledges particular circumstances when technology can be connective or inclusive. But it also notes that the push to individualize learning through digital technologies and online learning environments “may be missing what education is all about.” That is, education is largely a social and relational practice that requires us being together in space and time.

2. Educational technology in schools is a business with a profit agenda.

The authors find that to “understand the discourse around education technology, it is necessary to look behind the language being used to promote it, and the interests it serves,” and that most of the evidence of the value of ed-tech in schools is produced by the companies selling it.

Educational institutions need to know that investing in ed-tech alone won’t solve long-standing inequities or challenges in education. Neither should educational technology be employed as a means for cutting in-person learning education budgets.

3. “Education systems need to be better prepared to teach about and through digital technology.”

The report’s calls for more responsive curriculum, teacher training and engagement with youth online life echoes recommendations offered by a range of scholars in my edited collection, Education in the Age of Misinformation.

Young people are grappling with information abundance, hidden technological manipulation and an onslaught of mis- and disinformation. Banning cellphones in schools won’t address this complexity. Neither are outdated media literacy or narrow digital literacy curricula.

Rather, to complement the urgent call for government regulation of tech companies described above, we need comprehensive new literacy teaching that will make space for how students experience the emotional, psychological, cognitive and ethical demands of online and in-person life.

Despite the appeal of simplistic solutions, the way forward requires comprehensive government interventions. These would regulate technology companies, invest in the common good of in-person public education and develop whole-child curriculum that avoids moral panic and instead fosters critical literacy and social responsibility.

Author Bio: Lana Parker is aAssociate Professor, Faculty of Education at the University of Windsor