About 30% of my work week is classified as ‘service’: work that supports others in the community, such as sitting on committees, writing reviews and references, consulting on problems and so on. As a result of this higher than usual level of service work, the sheer number and range of things I do in a day can be bewildering.

Sometimes I feel like I work behind the counter at an academic delicatessen serving an endless line of hungry customers. Three thin slices of policy analysis? No problem. 100 grams of soothing hurt feelings about the feedback your supervisor gave you on that draft? I can do that for you – and I’ll throw in a book recommendation too. A medium size container of problem solving? How about a large one with a hand full of diplomacy? It’s on special this week!

Keeping up with all the multiple, sometimes conflicting demands is hard. Unfortunately all the people standing in the line at my academic delicatessen are invisible to each other and have no idea how busy I am. Sometimes I feel like I am flinging packages of intellectual cheese and salami at people at random. Then, into all this frantic motion, walks in that one customer. If you’ve worked in retail you know the sort. Their demand to be served right now seems thoughtlessly entitled given how many other customers are waiting for service.

This week that customer was a journal publisher asking for yet another peer review. “Can’t you SEE I’m busy!” I yelled at the screen.

To give you some context to my annoyance, in case you didn’t know already, the conventional academic publishing system is seriously flawed. Many academic journals are owned by corporations that leverage the free labour of academics into ‘share holder value’. This is a way of privatising public money that has many ramifications for our universities, as I have written about at more length elsewhere (see “The academic writer’s strike”).

I’m conflicted about publishing in journals because the system seems so broken. So I approach the problem using a simple formula. For every submission to a journal, regardless of whether it gets accepted or not, I do at least two reviews. In this way, in theory, I give back pretty much what I ask. But somehow it never works out that way – I always do more peer reviews than I planned.

So, despite my annoyance, I read this peer review request carefully. Unlike most of the requests I get, the paper was about research students. So I asked myself a harder question: does the paper actually look important? A quick read of the abstract indicated it was about supervision. There is a lot – I mean a LOT – published about research supervision. This one would have to be something special to convince me to spend time on it and unfortunately it wasn’t. Yet another, very small scale institutional case study. I’ve read masses of these and in my opinion, they don’t offer much more than what we already know, so I pressed ‘decline’.

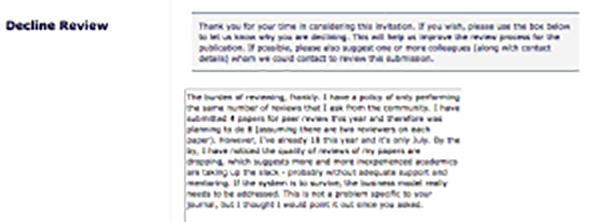

So far, so normal, but the link in the email immediately redirected to a request for me to refer the paper on to a colleague. This is when I got cranky at my demanding customer. Please bear in mind, I was tired. It was 11pm and I had been working in my academic delicatessen since 10am. For some reason the immediate request that I pass this on to yet another over worked colleague rubbed me the wrong way. I wrote a rather snippy reply, which you can see in the image below:

In case you can’t read it, my response was as follows:

In case you can’t read it, my response was as follows:

“(the reason I declined is) The burden of reviewing, frankly. I have a policy of only performing the same number of reviews that I ask from the community. I have submitted 4 papers for peer review this year and therefore was planning to do 8 (assuming there are two reviewers on each paper). However, I’ve already 18 this year and it’s only July. By the by, I have noticed the quality of reviews of my papers are dropping, which suggests more and more inexperienced academis are taking up the slack – probably without adequate support and mentoring. If the system is to survive, the business model really needs to be addressed. This is not a problem specific to your journal, but I thought I would point it out since you asked”

To be clear my comment wasn’t meant to infer that people who are inexperienced are always bad reviewers, or that experienced academics are necessarily great at it, but the overall drop in quality needs some explanation. That more inexperienced academics are being drawn into reviewing seems as good a reason as any; at least, it’s consistent with the general culture in academia of pushing un-wanted work onto junior colleagues.

I posted my rant to Twitter and Facebook and got a deluge of responses. Most people agreed with my sentiments, but some took issue with my interpretation and even called me selfish – a charge I reject whole-heartedly. Some people on editorial boards told me they had already reviewed 40 or 50 papers because people like me were hitting the ‘decline’ button more and more. Others told me that the reviews they got were dropping in quality too (a memorable line from a review received by a colleague in statistics was “what is this p-value thingy?”).

Look – I could be wrong. If anyone has any evidence that something else is going on, I’d love to hear it in the comments, but let’s assume for a moment that more and more junior colleagues are being asked to provide journals with peer reviews because senior people like me are not contributing enough anymore. What is the problem here really?

With my fulltime wage comes the expectation I will give back to my community and that my employer will be supportive. However, many early career academics have insecure employment and PhD candidates are on very low incomes. If these less advantaged academics are being asked to take up the slack, they are effectively being asked to prop up a disintergrating publishing system with their free labour. A system, I might add, that is also experiencing enormous growth due to pressure by our employers to have ‘outputs’ and, presumably, the publishing company share holders, who want to pocket the profits.

What are the consequences for the individual and academia more generally? More importantly, as a PhD student, how should you respond to this pressure?

‘Service work’, such as peer reviewing, is often presented to our junior colleagues as an ‘opportunity’ to add to the CV, not what it really is: free labour in the expectation of some kind of other, unspecified reward later on. In a recent paper I wrote with colleagues we called this type of work ‘hope labour’ (following Kuehn & Corrigan, 2013 – reference at the end of this post).

Asking people to contribute hope labour walks a fine line between providing opportunity and exploitation. In my view, before a PhD student or a paid-by-the-hour (or ‘gigging’) academic says “yes” to any service work request, it’s worth asking a few questions:

- If you have not done this kind of service work before: is this a good opportunity to develop new skills?

- If you have done this kind of work, how exactly does doing more of it benefit you?

- Will the service work be recognised in some way?

- Does this service work help you build your network in such a way that might lead to future (paid) opportunities?

If you can confidentally answer “yes” any one of these questions, the service work is probably worth doing. Now, let’s subject peer review requests to this rubric.

Aside from (potentially) keeping you abreast of new developments in the field, after you have done enough peer reviewing to get a sense of it, I question whether most PhD students or gigging academics should do more. I think the time is better spent reading over your colleagues’ manuscripts instead. Providing helpful feedback to those around you is a way of building a community of support and collegiality that is of immediate benefit to everyone, including you (as the saying goes, you have to earn the right to ask a favour). So, unless the paper promises to be fascinating, after you’ve done four or five peer reviews you might want to start saying “no” more often than “yes”.

Recognition can take many forms other than money: a certificate, the right to claim an association, a free lunch – whatever. One of the key problems with peer reviewing is there is little or no recognition. Journals sometimes send form letters as a thank you – but most often you get nothing. If you review regularly with a particular journal it’s worth asking for a testimonial from the editor saying you did a good job. If they are not willing to do this, seriously consider a blanket “no” in the future. Trust me there will always be others asking for your time.

From the academic networking point of view, peer reviewing for a journal is virtually useless. The whole point of peer reviewing is to be invisible, so your work will go largely un-noticed as well as unrewarded. Unless you have some kind of ongoing relationship with a member of a journal’s editorial board, very few of the people who matter to your future career are seeing you work and, more importantly, getting to know what you can do. Why not volunteer to be on an organising committee for a conference instead? This enables you to meet people and work alongside them – crucial for building networks that might eventually lead to paid employment.

So I call bullshit on journal publishers’ endless demands for hope labour, especially from PhD students. I recognise that academia needs a gift economy to operate, but it should be full time academics like myself doing the lion’s share – and I should not have to work past 11pm at night to satisfy the demands of for-profit companies. If you’re a fulltime academic, or a member of an editorial board, I hope you think carefully about the opportunity you are really offering before you invite someone with less status and salary than yourself to do extra work. And seriously, if we can’t keep this shop open without people being decently compensated for their work, we might want to think about closing the doors on our current model of peer review publishing – for good.

What do you think? Maybe you disagree? Maybe you can shed some light on the problem? Or perhaps you want to share your experience of hope labour to help others work out what work to accept and which to reject. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Reference

Kuhen, K & Corrigan TF 2013, ‘Hope labor: The role of employment prospects in online social production’, The Political Economy of Communication, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 9-25.