Tomi Ungerer’s Giant of Zéralda has become what we call a classic for young people. Criticized by adults, when it was published in 1971 in L’École des loisirs because it challenged the codes and laws of illustrated storytelling for children, this album was immediately adopted by young audiences whose pleasure can never be denied. since.

Excellent sesame to enter the mischievous and dynamic world of Ungerer, The Giant of Zéralda tells in drawings and in words how a voracious and shaggy ogre becomes a prince charming and how an innocent little girl turns into a fulfilled young woman.

This modern tale is the story of a vigorous socialization process . His quest – and our investigation – boils down to this deceptively simple question: “What is growing up?” ”

There is the ogre first …

He tumbles into fiction with his big teeth, his big nose, his bloody knife, his limitless appetite. Coming from elsewhere abandoned to devastating forces, he savages everything in his path. The neat city where he comes to stock up on fresh meat is turned upside down. A real de-civilizing thrust falls on the humans who hide themselves like animals. The children, hidden at the bottom of the cellars, have disappeared.

Soon the ogre can no longer satisfy his voracity. It only remains for him to mumble children’s rhymes which, alas, do not make his favorite dish appear. Stuck in the margins of the savage where destructive impulses reign in an “animalized” universe, the ogre thus acts in a sterile manner.

Giant as he is, he is still in the infancy of socialization: he absolutely must grow up. To move from nature to culture, from animals to humans, he will have to fit into a network of prohibitions and obligations …

There is Zéralda too …

Six years old, she lives, in the middle of the forest, in a clearing where the ogre is unknown. His father cultivates the fields. Her mother is dead and the little girl is looking after the house. An outstanding cook, she prepares all kinds of dishes and reads recipe books diligently.

She is an artist who puts snails in jars, canned fruit and hares in pâté! She knows how to domesticate the savage, to civilize it, to de- wild it .

One day on the way to the market, the little girl meets the ogre. He waits for her at the turn. It’s inevitable ! She must of course free herself from her father’s guardianship and discover the world. The ogre and Zerald have to grow up, and they need each other to socialize.

The rite of passage supposes to be accomplished, as we know, a necessary co-operation. And the initiation work, of which the album tells us, shows how each character learns to act and how one in relation to the Other at the initiation of the initiation.

And there is especially the ogre and Zéralda …

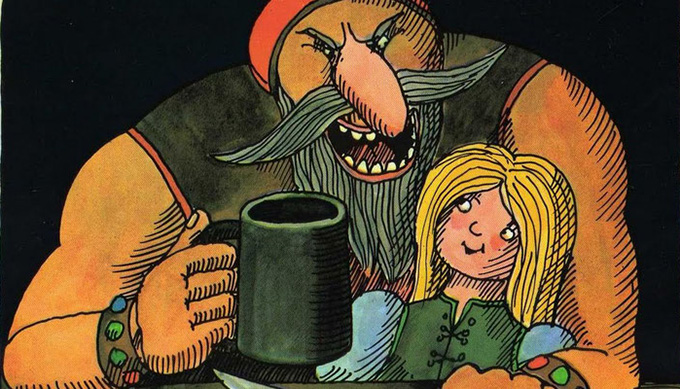

When Zéralda meets the ogre, he is so hungry and weakened that he passes out in the middle of the road. She only sees a poor man suffering and immediately initiates him into cooking , this transformative activity which – as Lévi-Strauss has shown – combines nature (the raw) and culture (the cooked).

By drawing generously from the provisions that fill her cart, she prepares a splendid picnic. Tablecloth, cutlery, written menu, delicate dishes are offered to the enchanted ogre. Not only does it suit smoked trout with capers, but it also works on table manners. It can undo and move the limits: the edge of the path becomes a domestic space where you eat while delicately holding your spoon.

Completely won over, the giant asks Zéralda to come to his castle to exercise his talents. She accepts. In doing so, she helps the ogre and his friends, the surrounding ogres, to move from confused areas, abandoned to wild behavior to a world where social relationships are mastered. The loneliness of the bloodthirsty glutton is replaced by the conviviality of banquets!

But Tomi Ungerer’s Zéralda is not content with her knowledge and her culinary power, she always associates them with the practice of writing. Not content with cooking like a chef, she cooks the alphabet! She fills books and cookbooks with her new recipes.

Any extraordinary menu is transformed into a page of writing. Also the ogre eats while reading and reads while eating. He then learns to detach himself from native orality (that of childhood rhymes mumbled at the beginning of the album and linked to the immediate and disorderly satisfaction of desires) in order to access graphic order.

In our highly literate societies, the written word and its effects on the relationship with oneself and with the world are thought of as the domestication of wild thought and the rationalization of cognitive and social activities ( Goody ).

We can say that the metamorphosis of the ogre is due as much to the cooked dishes as to the calligraphy menus. It is true that the denomination of the dishes by Zéralda does not lack humor or intelligence. Her “Little Girl’s Croque on Ogre Delights” is a subtle example.

He tilts the ogre into metaphorical reformulation and the symbolic order where one no longer confuses words and dishes, signs and their referents. And in the world of language that is now his, he can eat like an ogre, a civilized figurative expression that means eating plenty!

Finally, there is the end of the story …

Years passed. It takes time to grow up… The ogre must get out of the cyclical time when he came to town every day to devour children to enter biographical and historical time, the time of changes and evolutions.

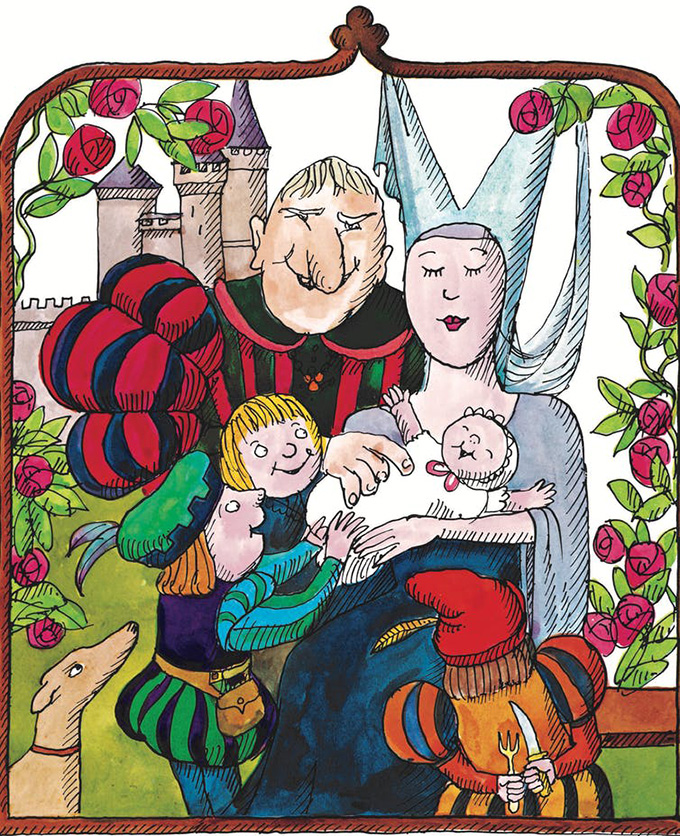

The two characters have now become two “socialized” adults and fall in love with each other. On the last page, you might think that Tomi Ungerer is reverting to the traditional genre of the tale “They married… had a large number of children. ”

But make no mistake, it is only to play a malicious snub at this formula from another time. The author adds immediately afterwards: “One can imagine that their life was happy until the end. »Opposite, the drawing shows a happy family gathered around the last born … except that one of the children is holding a knife and a fork behind his back.

The coexistence of the pacified and the wild seems very fragile. The limits can always be erased! The end of the story then opens up possible narratives that the classic tale generally closes. This false closure goes back to the beginning of the story. Repetition, restarting. The end appears as an endless end. Indeed each child will have to walk, in turn, the path which leads to adulthood.

“One can imagine that their life was happy until the end. » The leisure school

On closer inspection, the only one who really sees that the story is not over and will start over is the reader. The ogre and her children have their eyes fixed on the newborn baby that Zéralda, her eyes closed, is holding in her arms. If the characters cannot spot the presence of the little budding ogre, the reader must see him!

For the rite of passage to be accomplished, for the child who reads to be initiated and perhaps in turn become an initiator, we must open his eyes! This is exactly what the textual and iconic device imagined by Tomi Ungerer does in his last double page.

If, by definition, a biographical rite (being born, first entering school, etc.) does not start again, the reading of the literary account of the rite can be repeated as many times as necessary. Let the little ones read, reread The Giant of Zéralda so that they can move forward more confidently on the path of learning because we all have something of the ogre and something of Zéralda within us.

Author Bio: Lecturer in Literature at the University of Lorraine