The phenomenon of citizen science is not new, but it has grown over the last decade. Moreover, you yourself may have contributed by observing birds from your balcony or garden during the 2020 confinement, or by using your smartphone to identify a plant or an insect during a walk in the forest. In doing so, you shared your observations with scientists who use them to describe biodiversity and understand its evolution. But how do you know how much you helped them? In ecological research, this approach has a real impact on scientific publications, especially on themes that make the link between society and the environment.

Participatory science is defined as the production of scientific knowledge in which people whose profession is not involved are associated, who participate in an active, deliberate and often voluntary manner. Participatory sciences are well developed in the field of health , human sciences , and even in astronomy . However, it is in the field of environmental sciences and ecology that this approach to opening research practice to non-professional actors is most widespread.

Why, or for what reason, participate?

For ecological scientists, the participation of non-professional actors in research provides access to data that would otherwise be inaccessible, or at a pace that is too slow, incompatible with the need for scientific knowledge in the face of the ecological emergency. The Pl@ntNet and iNaturalist platforms rely on photos taken by nature-curious people, identified by an algorithm and validated by the user community. They allow a census of biodiversity on a very large scale and over a long period of time.

Several authors have analyzed the public’s motivation to engage in citizen science programs . What often comes up is curiosity and the wish to learn more about a subject (for example, learning to recognize plants or birds ), but also the desire to be useful , looking for a on the one hand, and the preservation of the environment on the other.

The link between usefulness for research and usefulness for the environment must be understood, very schematically, by following this sequence: observations provide data, which are analyzed, leading to the publication of a scientific article, which makes it possible to put in place concrete measures for the environment.

This is obviously very caricatured. Too much, because upstream of this sequence, a body of knowledge and theoretical constructions guide scientists in the way of asking research questions and defining data analysis strategies to answer them. It is also obvious, but it must be remembered, that the applications of research results in terms of environmental management strategy are not based on one, but on a set of scientific articles.

Hence a simple question: do participatory science approaches contribute to the production and evolution of scientific knowledge in the field of ecology? In other words: “Am I really useful if I participate”?

Note in passing that this question is legitimate on both sides of participation, for volunteers and for scientists. The acquisition of certain data may in fact require solid naturalist knowledge or the handling of complex or expensive sensors. In such cases, one may question the relevance or accuracy of observations made by people who are not specifically trained.

This therefore leads us to a second question: do we produce the same knowledge when research is carried out by professionals only, or through the participation of volunteers whose degree of expertise varies?

What is my participation really for?

We sought to answer these two questions in an article published open access in the journal Ecology and Evolution . We used a bibliometric approach to evaluate the impact of participatory science on the evolution of ecology as a scientific discipline.

We queried the Web of Science database , an international reference, to find all articles mentioning participatory science and published over the period 2011-2022. We identified more than 3000 articles about participatory science in ecology. This represented less than 1% of the total number of ecology articles published during this period, but this number was constantly increasing.

From a strictly quantitative point of view, the answer is clear: participatory science is published. A recent study shows not only that this is the case, but that articles based on them are also cited by researchers. Scientific articles being the basis of the dissemination of knowledge, this is a first indication that participatory science, and therefore the participation of volunteers, contributes to the advancement of knowledge in ecology. What about in detail?

Figure 1. Evolution of the number of articles on participatory science in ecology between 2011 and 2022. The horizontal axis represents the year of publication. The vertical axis indicates the percentage of articles in ecology relying on participatory science. The absolute number of citizen science articles published each year is shown inside the figure. Bastien Castagneyrol and Baptiste Bedessem , Provided by the author

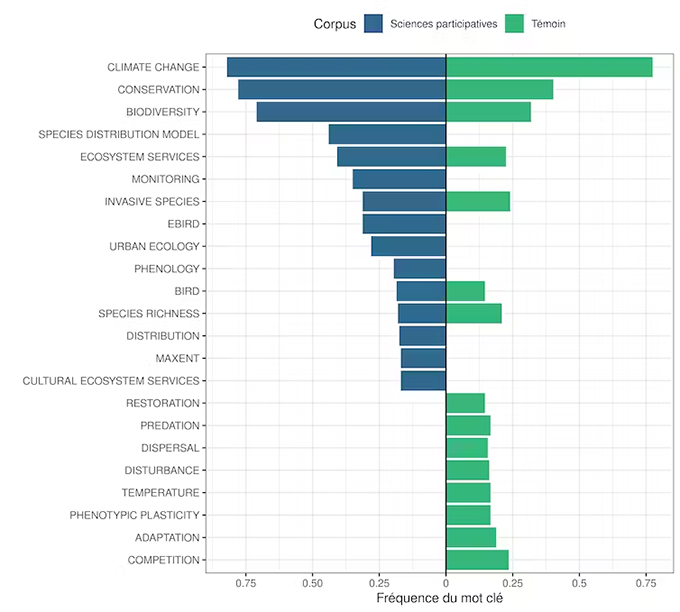

To put it simply, let’s call SP the corpus of articles based on participatory science. We compared it to a control corpus, assembled by randomly drawing the same number of articles from those published in ecology over the period 2011-2022. We extracted the key words used by the authors of the articles in these two corpora to compare them. This approach allowed us to determine whether the same themes are addressed in articles based on participatory science (the SP corpus) and conventional articles (the control corpus).

We found some similarity in the most frequently used keywords in both corpora. Over the last two years, biodiversity (the key words biodiversity , conservation ) and climate change have been at the heart of ecological research, regardless of the approach used (participatory or not) by ecologists to address these subjects. There are, however, subtleties in the detail.

Looking more closely at the differences in the use of the most frequent keywords in each corpus (how keywords are associated with each other), a major difference emerges between the articles in the SP corpus and those in the control corpus. Key words linked to ecological processes (predation, competition, dispersal, etc.) or evolutionary processes (phenotypic plasticity, adaptation) were more frequent in the control corpus, or even only present in it. On the contrary, key words linked to interactions between human beings and their environment (socio-ecosystems, ecosystem services, cultural services, urban ecology) were more frequent, or present only in the SP corpus.

Figure 2. Main keywords describing the articles in the SP corpus and the control corpus. Bastien Castagneyrol and Baptiste Bedessem , Provided by the author

The key word associations in the SP corpus are also revealing of the way in which the themes “biodiversity” and “climate change” are approached in participatory sciences. These themes were associated with keywords suggesting a descriptive approach to biodiversity, for example monitoring , species distribution , or species distribution model .

It therefore seems that when scientists use participatory science approaches, it is above all to describe the state of biodiversity, the way in which it is impacted by global changes (notably climate change and urbanization), and the consequences that this can have on the functioning of socio-ecosystems (the whole formed by the ecosystem and the human activities that take place there). The key word associations in the control corpus instead referred to the mechanisms governing interactions between species. This difference can be explained by the fact that people contributing to participatory science are more able to get involved in projects that directly affect them than in more theoretical projects.

Participatory science in ecology contributes significantly to the production of new knowledge that fits into the major questions that concern ecology. This is enough to reassure people who give their time and energy by voluntarily participating in these programs: yes, they are useful. There is also something to reassure ecologists: participatory science is not on the fringes of traditional research in ecology, it fits perfectly into the toolbox that scientists have at their disposal to describe and understand the world in which we live.

Author Bios: Bastien Castagneyrol is a Researcher in Ecology and Baptiste Bedessem is a Researcher at Inrae