Science seems to be under attack in America, so much so that scientists and their supporters are marching in the streets.

President Donald Trump has publicly called climate change a Chinese hoax abetted by greedy scientists. He has linked vaccines to autism despite overwhelming scientific consensus against these claims. Vice President Mike Pence has denied evolutionary science, the very foundation of modern biology. Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s pick for director of the Office of Management and Budget, has questioned the fully established link between Zika virus and microcephaly and wondered whether “we really need government-funded research at all.”

In response, scientists are taking a stand. They are defending their work against what appears to be a new, more aggressive assault in the so-called “Republican war on science,” as the president threatens deep cuts to federal funding of scientific research.

When they march for science, they will do well to consider insights from the field of study known as the “rhetoric of science.”

Studying scientists’ communication

Before dismissing this recommendation as a perverse appeal to slink into the mud or take up the corrupted weapons of the enemy, keep in mind that in academia, “rhetoric” does not mean rank falsehoods, or mere words over substance.

Rhetoric is one of the original seven liberal arts. Aristotle defined it as “the faculty of observing, in any given case, the available means of persuasion.” Scholars like me who study the rhetoric of science analyze and evaluate the persuasive communication of scientists.

Although it draws from an ancient tradition, rhetoric of science is a relatively young field of study. It was born in the late 20th century, after historian of science Thomas Kuhn introduced the idea that science develops not through the steady accumulation of facts, but in revolutionary moments. With a paradigm change, the heliocentric model of Copernicus replaces the geocentric model of Ptolemy, Darwin’s natural selection overturns natural theology, plate tectonics wins over the theory of a stable Earth.

Kuhn’s call for a study of “the techniques of persuasive argumentation” within scientific communities that settle conflicts between paradigms introduced the “rhetorical turn” in science studies. Rhetoricians enthusiastically took up the call to look at the way that language and culture help to shape knowledge.

At first, this kind of scholarship seemed hostile to scientists.

In the age of “alternative facts,” it is worth remembering that for most of the 20th century, the image of the scientist as American cultural hero was ascendant.

Scientists have long presented themselves in public as the inheritors of an American pioneering ethos, the very embodiment of the American spirit of exploration, innovation, hard work and success. You see it in influential engineer Vannevar Bush’s “Science: The Endless Frontier,” the report that spurred the formation of the National Science Foundation. Geneticist Francis Collins frequently drew an analogy between the Human Genome Project and Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery. This characterization was so powerful that even George W. Bush, a Republican president widely critiqued for his administration’s misuse of science, found it necessary to praise scientists as modern-day American “pioneers.”

In the latter part of the 20th century, when scholars began pointing out that the most effective scientists were those who were also the most effective rhetors, the validity of scientific theories and the institution of science itself seemed to be under attack. Rhetoricians got caught up in the “science wars” between postmodern deconstructionists and natural scientists. They were viewed with distrust by defenders of science.

Next phase for rhetoric of science

But times changed. In the early years of the 21st century, the two cultures of the humanities and the sciences found themselves united against forces that would starve higher education of funding. Many rhetoricians began to see their mission not as taking scientists down a peg or two, but as helping scientists improve their public communication.

For example, Celeste Condit draws from the rhetorical tradition to help medical geneticists appreciate the importance of understanding their audience. Scientists should be careful not to underestimate the public, which “knows a fair amount about the basics of heredity.” But neither should they neglect how certain terms affect the public mind. When telling individuals they have a genetic predisposition to cancer, for example, “version of a gene” is a less scary use of words than “mutation,” which evokes horror movie monsters.

Condit’s students, Marita Gronnvoll and Jamie Landau, explore the problems and potentials of the most frequent metaphors used by the public to discuss genes, such as ticking time bombs and Russian roulette. They recommend that scientists introduce new, more accurate and less alarming metaphors that call to mind the choreography or orchestration of a gene/environment interaction.

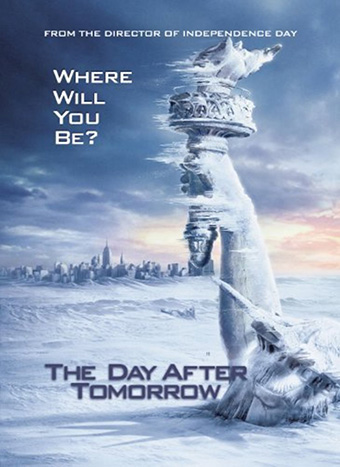

Rhetoricians have advice for climate scientists too. Ron Von Burg introduces the rhetorical concept of litotes as a way for scientists to respond to inaccurate but emotive imagery. Litotes is a figure of speech that works as an understatement by stating the negation of its opposite; imagine a friend hinting that an invitation to visit would “not be unwelcome.”

While the scenarios in the movie won’t happen the day after tomorrow, scientists signaled that the message ‘wasn’t untrue.’ Twentieth Century Fox

Ethos, or the speaker’s development of a trustworthy character, is another important concept that rhetoricians share with scientists engaged in public debates. Jean Goodwin has studied how scientists can reach out to skeptical listeners with appeals that signal their vulnerability rather than their superiority. Observing climate scientists speaking to skeptical audiences, she has found that one must give trust in order to receive it in return.

Some of my own research focuses on how to counter a manufactroversy: when the public has been told there’s a dispute within the scientific community when there is actually a wide consensus. In these cases, those who would manipulate the public set argumentative traps. One way for scientists to avoid these traps is to point to the history of scientific debate that resulted in the consensus of experts. Sharing such rhetorical strategies is my way of helping climate scientists, as well as experts responding to those who deny the safety of vaccines, or the link between a virus and a disease.

When scientists gather to march for science, I want them to know about this body of research. In addition to carrying signs, they can take up the toolbox of effective communication known as the rhetorical tradition. Rhetoricians will be marching by their side, allies in the battle to protect science from politically motivated attacks on one of the greatest treasures of the nation.

Author Bio: Leah Ceccarelli is Professor of Communication at the University of Washington