Searching online has many educational benefits. For instance, one study found students who used advanced online search strategies also had higher grades at university.

But spending more time online does not guarantee better online skills. Instead, a student’s ability to successfully search online increases with guidance and explicit instruction.

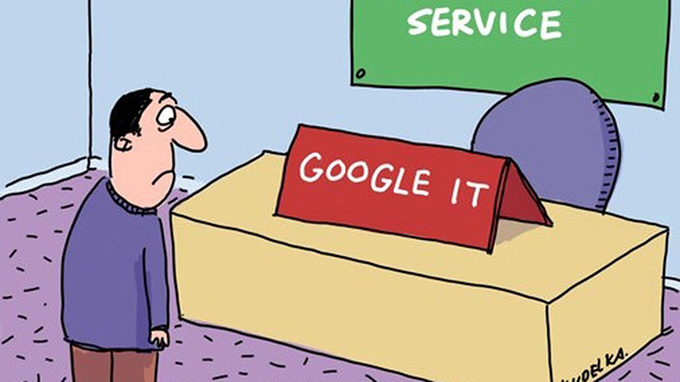

Young people tend to assume they are already competent searchers. Their teachers and parents often assume this too. This assumption, and the misguided belief that searching always results in learning, means much classroom practice focuses on searching to learn, rarely on learning to search.

Many teachers don’t explictly teach students how to search online. Instead, students often teach themselves and are reluctant to ask for assistance. This does not result in students obtaining the skills they need.

For six years, I studied how young Australians use search engines. Both school students and home-schoolers (the nation’s fastest growing educational cohort showed some traits of online searching that aren’t beneficial. For instance, both groups spent greater time on irrelevant websites than relevant ones and regularly quit searches before finding their desired information.

Here are three things young people should keep in mind to get the full benefits of searching online.

1. Search for more than just isolated facts

Young people should explore, synthesise and question information on the internet, rather than just locating one thing and moving on.

Search engines offer endless educational opportunities but many students typically only search for isolated facts. This means they are no better off than they were 40 years ago with a print encyclopedia.

It’s important for searchers to use different keywords and queries, multiple sites and search tabs (such as news and images).

Part of my (as yet unpublished) PhD research involved observing young people and their parents using a search engine for 20 minutes. In one (typical) observation, a home-school family type “How many endangered Sumatran Tigers are there” into Google. They enter a single website where they read a single sentence.

The parent writes this “answer” down and they begin the next (unrelated) topic – growing seeds.

The student could have learnt much more had they also searched for

• where Sumatra is

• why the tigers are endangered

• how people can help them.

I searched Google using the key words “Sumatran tigers” in quotation marks instead. The returned results offered me the ability to view National Geographic footage of the tigers and to chat live with an expert from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) about them.

Clicking the “news” tab with this same query provided current media stories, including on two tigers coming to an Australian wildlife park and on the effect of palm oil on the species. Small changes to search techniques can make a big difference to the educational benefits made available online.

2. Slow down

All too often we presume search can be a fast process. The home-school families in my study spent 90 seconds or less, on average, viewing each website and searched a new topic every four minutes.

Searching so quickly can mean students don’t write effective search queries or get the information they need. They may also not have enough time to consider search results and evaluate websites for accuracy and relevance. .

My research confirmed young searchers frequently click on only the most prominent links and first websites returned, possibly trying to save time. This is problematic given the commercial environment where such positions can be bought and given children tend to take the accuracy of everything online for granted.

Fast search is not always problematic. Quickly locating facts means students can spend time on more challenging educational follow-up tasks – like analysing or categorising the facts. But this is only true if they first persist until they find the right information.

3. You’re in charge of the search, not Google

Young searchers frequently rely on search tools like Google’s “Did you mean” function.

While students feel confident as searchers, my PhD research found they were more confident in Google itself. One year eight student explained: “I’m used to Google making the changes to look for me”.

Such attitudes can mean students dismiss relevant keywords by automatically agreeing with the (sometimes incorrect) auto-correct or going on irrelevant tangents unknowingly.

Teaching students to choose websites based on domain name extensions can also help ensure they are in charge, not the search engine. The easily purchasable “.com”, for example, denotes a commercial site while information on websites with a “.gov”(government) or “.edu” (education) domain name extension better assure quality information.

Search engines have great potential to provide new educational benefits, but we should be cautious of presuming this potential is actually a guarantee.

Author Bio: Renee Morrison is a Lecturer in Curriculum Studies at the University of Tasmania