How to react to the whims and acts of disobedience of a young child? Sending him to his room to punish him, is that being too strict or does it amount to setting necessary limits for him? In this spring of 2023, psychologists and families are again divided on these questions, reviving the debate around an education without constraint and without sanction, or “positive” – an ideal that could cover sweet and dangerous illusions.

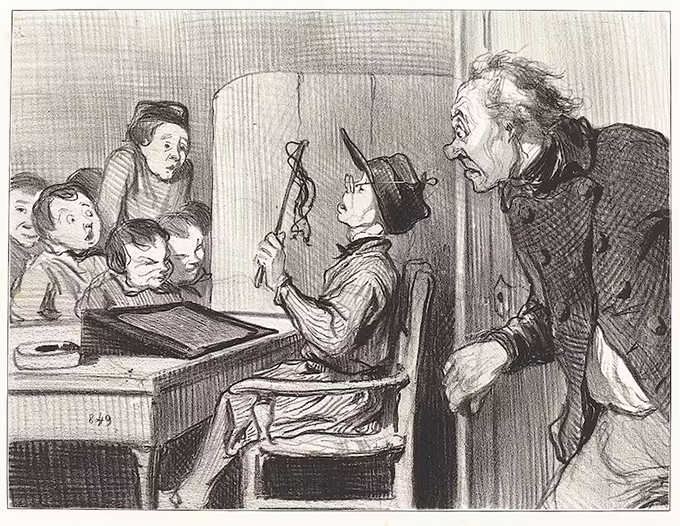

No one will dispute that the educational process had to be rid of all physical and psychological violence. The educational brutality of past centuries is chilling. From the ferrule to the dunce’s cap, from the pensum to the dungeon, the list of punitive practices deployed is terrible and almost infinite, as shown by the Dictionary of whipping and spanking recently published by the Presses Universitaires de France. The world of literature has not failed to echo these excesses. Let us think of Balzac in Louis Lambert , Jules Vallès in L’Enfant or even Paul Verlaine in Mes prisons .

However, banning all forms of violence does not amount to condemning authority. Constraint has its virtues, sanction too. It is amazing in this debate to see how educational history is often falsified, or even simply forgotten.

School without constraint: the failure of a utopia

Let us recall that a school without constraint and without sanction already existed, through the experience of the master-comrades of Hamburg , in the 1920s. of punishment or sanction, that there would no longer be any question of prohibition or of any regulation whatsoever which could hamper them in their use of their full freedom”, writes Jakob Robert Schmid who relates this astonishing experience in Le maître-comarade and libertarian pedagogy .

The masters of Hamburg thought that only freedom, understood as the absence of constraint, could bring out the treasures of childhood. The teachers no longer wanted to be teachers: “We finally want to begin to live fraternally with the children of the school: we want to live with them as true comrades.

“Wait… I’ll give you some… from the schoolmaster”, Honoré Daumier, lithograph, 1846. National Gallery of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia

This experiment embodied in its most radical form the utopia of an educational space purged of all forms of constraint. It ended in resounding failure, all the more bitter in that, for more than ten years, these innovating masters showed uncommon enthusiasm. Zeidler, one of the inspirations, had to admit, not without sadness, that

“wherever one allowed oneself to be guided by a boundless confidence in the tact of children, in their strength of will, in their perseverance, in the sureness of their instincts and in the tolerance of individuals to form a community […], we saw the formation of bands of undisciplined people”.

Make no mistake, the child needs to be guided and sometimes constrained. Freud says it, could not be more clearly, in his New Lectures : “To give him the freedom to follow all his impulses is impossible. It would be a very instructive experiment for the psychologists, but the parents would not be able to stand it and the children themselves would suffer serious damage”. Educational work calls above all to encourage, support, value, but it cannot do without prohibition.

The educational scope of the sanction

Followers of the neither-nor ideology (neither constraint nor sanction) often refer to support their thesis to educational experiences which, contrary to what they may say, have never banished sanction. The school of Yasnaya Polyana , opened by Tolstoy in 1859 for a few short years, and which is often cited as a model, in fact resorted to exclusion and deprivation.

Maria Montessori is also summoned. However, the Casa dei Bambini , which brought together very young children, mentions in its rules of procedure of 1913, that the “unruly” and the “neglected and dirty” children will be expelled from school. There were also sanctions at Summerhill, the school founded in 1921 by Scottish pedagogue Alexander Neill , and which was intended to be a free place. However, what do we discover there? Sanctions such as fines, warnings, corvée were distributed there… by other children set up in court. Progressivism is not always where you think it is.

Generally speaking, the schools which have claimed to avoid any sanctions are often schools which have taken in restricted or even selected students, thus contravening the principle of hospitality. They are also schools that have hidden their punitive practices under so-called “natural” sanctions. Finally – something that is hardly admissible – schools where adults have got rid of the right to punish to bequeath it to children, as was the case in the famous school of Summerhill.

The most innovative perspectives are not those which have attempted to oust the reality of the sanction but those which have endeavored to give it an educational scope. In particular, they have shown that an educational sanction always pursues a triple end: to reaffirm a shared rule, to empower a young person growing up and to set a limit for him. They also showed that an educational sanction could take a private form.

The educational sanction is suspensive, it temporarily suspends a right, a power. It narrows, for a moment, the field of possibilities and opportunities. With a sentence, she momentarily reduces the power of the subject. “I won’t speak to you again because you haven’t stopped saying unpleasant things this afternoon”. “I stop helping you because, on your side, you don’t do what you have to do, you don’t respect the contract”. “Go back to your place, you can join us when you really want to work and get involved”.

Let’s stop thinking of the sanction as a penalty, it is no longer on the agenda, the page has been turned. The sanction is not there to hurt but to make sense. It can also, in certain circumstances, take a restorative form. “You have soiled this wall, now you are going to wash it”; “You keep annoying little Paul, you’re going to show him what it’s like to be big, and you’re going to help him with his homework until the end of the week.” To repair is certainly to repair something, it is also and above all to repair someone.

The rule, constraint and guarantee of rights

The neither-nor ideology is now returning at a gallop with positive education. As Denis Jeffrey, professor of education at the University of Laval , has clearly seen , we start by keeping quiet and renaming. We play on words instead of thinking: “The teacher becomes a guide or a facilitator, the rule an expectation, the punishment a consequence”.

Let’s assume the words: a teacher teaches, a rule is a rule. Perhaps it is good to remember that there are three lines of meaning in the idea of a rule:

- Who says rule says regularity. A rule is what recurs on a regular basis, in this sense it is predictable;

- Derived from the Latin “regere” (to direct), the rule constrains;

- Finally, let’s not forget, it guarantees rights. To educate is not to imagine stratagems to conceal social rules under so-called natural constraints, as Rousseau suggests in Émile ; to educate consists in making the child pass from a religious conception of the rule to a legal conception, from Themis to Nomos .

Because the first conception is always religious. The rule is inevitably apprehended by the child as a transcendent (external) and immutable instance. It is experienced as a limit to his projects, his desires and his desires. Impressive and intimidating, it incites, as paradoxical as it may seem, to play and transgression.

To grow is to open up to a legal conception that encloses three distinctly different characteristics. The child understands that one can participate in the construction of the rule. Certainly, once elaborated, it attains a form of transcendence, but this transcendence is secondary. It is also modifiable: it can be changed, improved, adapted. The rule is then experienced less as a limit than as a link. It connects us by demanding the same duties and guaranteeing the same rights. The heart of educational work is precisely to bring each child into this peaceful and intelligent relationship with the rule.

More fundamentally, how not to see that, in the educational process, constraint has its place. Let’s say it already, it is not violence. It appears immediately as negative, but it encloses a positivity because it is an invitation to become other. When it has become self-constrained, it is retained while being exceeded because the ability to self-constrain offers the ability to make oneself available. Constraint no longer constrains me, it frees me because “true freedom, as Montaigne said, is to be able to do anything over yourself”.

Author Bio: Eirick Prairat is Professor of Philosophy of Education, member of the Institut Universitaire de France (IUF) at the University of Lorraine