Education should prepare young people to face the challenges of their time. To keep up with the changing world, this means that education has to keep adjusting. But unfortunately, our education systems have fallen out of sync with the times.

Environmental decay is arguably the greatest challenge facing humanity today. However, education systems are failing to prepare young people for life on a rapidly changing planet.

One way to escape this trap is to shift our perspective on the period of time we inhabit. Instead of the 21st century, we might think of ourselves as living in the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene is a proposed new geological epoch – a unit on the geologic timescale – characterised by unprecedented human influence over the natural environment. While a panel of geologists decided against declaring the Anthropocene an official geological epoch in 2024, there’s no doubt that it remains a powerful way to understand the world around us.

Thinking of “our times” as the Anthropocene – official epoch or not – rather than the 21st century forces us to confront “deep time”. This means considering what our society is doing to the planet not just during our individual lifespans but over the long term, before we were born and after we die.

This could be, for example, considering how sea level change might affect the places we live in a hundred – or a thousand – years’ time, and what life might be like then.

Educating differently

Recent education policy has often focused on “21st century skills”, an idea that stresses the new challenges brought by an interconnected post-industrial society, such as navigating the benefits and pitfalls of new communication technologies. Concepts like “critical thinking”, “collaboration” or “creativity” have become increasingly influential across many education systems around the world.

But the problem with this approach is that it reduces learning to an instrument to grow the economy. The “21st century skills” are now so commodified that we can almost think of them simply as tickets to the job market.

Critical thinking has come to mean “problem-solving for infinite growth” rather than an ability to truly reflect critically on our society’s values and practices.

Shifting the focus to think about the long term shows us just how inadequate the idea of 21st century education is at tackling the challenges we face, including environmental degradation.

My research has focused on what an education fit for the Anthropocene might look like. Right now, this education often takes place outside school walls, such as among grassroots environmental movements. In my work, I argue that schools would do well to take a cue from these “alternative” spaces of learning if they are to remain relevant.

This requires an emotional connection with what we learn. If we grasp what is at stake in the Anthropocene (the survival of our own species, among other things), we cannot help but care.

Learning with emotion

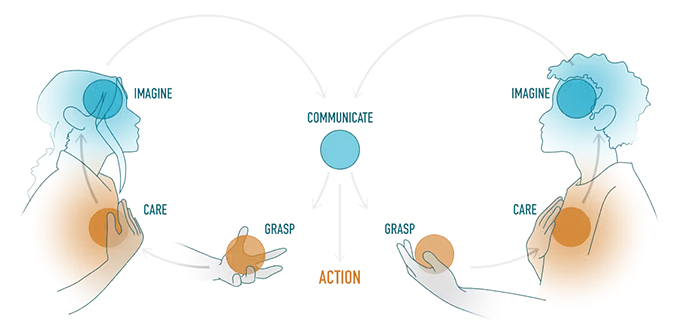

This emotional response fuels our imagination of different futures, which we can communicate to others, with whom we can act. It is a circular process: once we have communicated and acted with others, we might realise there was something we did not fully grasp, which makes us change our vision of the future, and communicate this to others.

Educating for the Anthropocene in action. Peter Sutoris and Nuith Morales, CC BY-NC-ND

This could mean many things in different contexts. In my own work as an educator, I have tried methods like participatory filmmaking with students or exposing my students to art that engages with the emotional aspects of the unfolding environmental crises.

Rather than contributing to economic growth, the goal of education in this process is to help us realise our nature as beings that can grasp complex issues, care about them, communicate about them and act to change them. It means removing the obstacles that might get in the way of our ability to realise these aspects of our humanity.

Education fit for the Anthropocene is, in other words, simply an education fit for understanding what it means to be human.

Author Bio: Peter Sutoris is Assistant Professor of Education and Social Justice at the University of Leeds